Having maintained a schoolboy interest in optics and physics and mathematics, I wanted to build a stereoscopic device to create 3D radiographic images so that I could demonstrate to my teachers my ruminative concepts on volumetric facial radiology. Eventually I made a simple 3D radiographic model of a face. With it I could effectively demonstrate the acquisition and diagnostic simplicity of volumetric imaging. This thing seemed real. It shimmered just in front of the viewer and showed everything in perfect fidelity and accuracy; behind to front, side to side. It was very dramatic when I first saw it, and for everyone since that has seen it too.

After contacting a German engineering scientist who had written on a similar concept decades earlier, soon enough I had a couple of German employees of Siemens visit me in New Zealand to see my setup. I used my physical model as a visual means of explaining the mental image of the future of maxillofacial surgery that I had. I explained that digitizing a series of plain radiographs from a rotating x-ray machine, assigning numerical values to the grayness of the pixels in the image, and then cross-referencing the values to adjacent images obtained in a circle and traveling around an object would enable a suitably powerful computer algorithm to build up the pixels (now voxels) into a 3D space. The Germans were developing this same idea for use in cardiothoracic and arterial imaging using the 1984 work of Feldkamp, Davis, and Kress. While I had no idea how to develop an algorithm to accurately 3D fix the gray value points, I was adamant that the technology, if developed, would be extremely useful in dentistry and for maxillofacial surgery in particular.

I was sure that a dentist could have a unit in the office no bigger than an orthopantomogram machine and three dimensionally image things as fine as a tooth’s root canal system or see entire dental arches and bites.

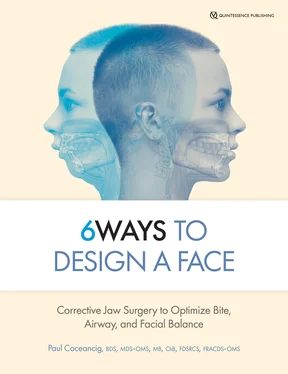

For me, all I wanted was a simply acquired means of explaining that the face, teeth, jaws, and everything else were part of one complex 3D object. I wanted to be able to see into, expand, revolve, and better imagine facial growth disorders and the corrective jaw surgery steps needed to manage them. Once I had that, I could then describe the symmetry and proportions of the skeleton and dentition of a face. And then I could scan many people and compare them, and see patterns, and maybe move on from there. But I never heard from the German Siemens scientists again.

Many years later, I ran into my old boss, Leslie Snape, at a conference. He told me he still has my invention sitting on a bench in a closed room somewhere in the bowels of Christchurch Hospital. He calls it the original cone beam. I just laugh. I call it a Kiwi version of cone beam. If it can’t be made with pantyhose and sheep-fencing wire, it’s not worth calling it a practical invention. (That’s a Kiwi joke.)

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Today of course, we have software applications much more sophisticated than cone beam that can accurately duplicate the entire head, segmentalize it, and separate the component parts. It’s upon this digital version of the patient that we can replicate real-life surgery and the volume changes affecting tongues, airways, faces, temporomandibular joints, and bites. One of the best things about digital imagery is that you can start explaining complex things to your patients. It means that I can reduce a compound anatomical narrative to the common language of the visual medium. I still need a certain kind of intellectual ability on the part of my patients, but increasingly the patients who do independently find me are naturally skilled in broad research and innate logic.

Over the years my jaw surgery practice has naturally divided itself between two broad arms.

The first is that I am providing some form of remedial surgical treatment, usually well after orthodontics has come and gone, and usually only in adults who are deliberately seeking my direct care. The majority of these people snore or have health or lifestyle issues related in some way to their ease of breathing. These people find me because they researched their personal symptoms, asked themselves logical questions, and sought a means to explain everything that has and is happening in their lives as one set of interrelated health issues. These people are generally free of an orthodontist referral.

In effect, I offer two ends of a stick. One is a simple end where I use a simple operation to prevent bigger problems, and the other is a complex end where I treat really big problems using really big operations.

The second arm usually involves young adolescents who are accompanied by parents, who have first brought their child to an orthodontist, usually for an overbite correction. These patients usually have an orthodontist’s referral. They are usually the hardest to treat, firstly because they did not independently seek me, secondly because they require a complex and seemingly contrived explanation they do not really want to hear, and thirdly because parents naturally see jaw correction surgery as incredibly invasive.

The ironic thing is that IMDO (intermolar mandibular distraction osteogenesis) is the simplest surgical operation that I offer. It is even simpler than third molar removal, and it usually helps avoid the third molar surgery that is part and parcel of normal orthodontics for overbite correction (not to mention it helps avoid everything else too). But the greatest benefit of IMDO in this second practice arm is that it prevents these adolescent patients from becoming patients in the first practice arm—the adults who come to me for snoring or other problems that lead to jaw surgery remediation through remedial BIMAX (advancement of both jaws).

In effect, I offer two ends of a stick. One is a simple end where I use a simple operation to prevent bigger problems, and the other is a complex end where I treat really big problems using really big operations. Any medical enterprise has two ends like this. At one end are the treatments of the disease after it has occurred. At the other end is the research and the development and the application of treatments that prevent that disease from occurring in the first place.

Why do parents who have children with small jaws and big overbites persist with a belief that orthodontics alone fixes everything? If someone asks me what the true cost is of treating someone with a small jaw, then that total cost must include tonsillectomies, dentistry, oral surgery, orthodontics, TMJ therapy, rhinoplasties, chin implants, sleep studies, CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) therapy, and finally remedial jaw surgery. But I can only collate these costs if I tie all those things together as one linked or total series. So this question of whether adolescent dental crowding, or bad bites, or even small jaws has any other consequence apart from braces is obviously a very pertinent one. Is there really a link to adult obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)? Will the adult eventually insist on cosmetic intervention? Are impacted third molars inevitable or can they be prevented? Is there any way of correcting a bad bite before it starts? Is there any way to prevent snoring or OSA from ever developing?

There were a number of events that occurred in my life that set me on the intellectual and professional pathway that I now lead. At some point it occurred to me that a narrow dental arch was more a case of a narrow nasal airway. At some point it occurred to me that a small jaw and an obstructing tongue were part of the same condition. At some point it occurred to me that dental crowding and impacted teeth in adolescents presaged the development of OSA in late adulthood. At some point it occurred to me that everything that I was taught in becoming a dentist was not the sum of everything I could know and that it could be built upon.

Читать дальше