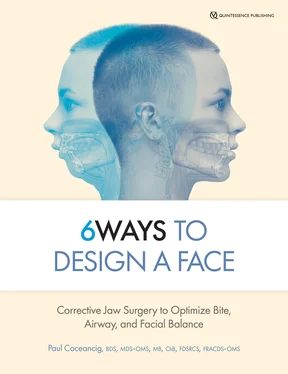

Over the course of my career up to this point, certain commonly held philosophies, tenets, and basic ideas concerning what is a face, what is abnormality, and what is considered corrective have all needed alteration. These questions and their evolving answers have shaped my thinking and conceptualization of the necessary solutions.

I suppose, in formulating a basis for what follows in this book, I first need to introduce who I am, where I came from, and what made me.

MY STORY

I began dentistry when I was 17 at the University of Sydney in Australia. The Australian profession was then, as it is now, extremely conservative. The professors all hailed from the Commonwealth, so we students became an ordered, intellectualized, and socially privileged group focused on the community benefit of uniformly applied oral health care. Australian style.

At 23, and newly graduated as a “dental surgeon,” I took a job at the local public dental hospital, and while my classmates were entering private practice and buying new cars and homes, I learned to extract teeth and started my fellowship studies with the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons, which opened the door to specialist training positions in oral surgery. This led me to meet Professor John Edgar deBurgh Norman AO, Associate Professor Geoffrey McKellar, and Drs Alf Coren and Peter Vickers, independently brilliant people who would take me into their hospitals and show me orthognathic surgery. I held a retractor and listened while they talked; they advised me to forget about extracting teeth and formed my intellectual connection to orthognathic surgery. Their confidence and mentorship supported an offer for me to enroll in a 5-year specialty oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMS) program across the Tasman Sea in New Zealand. I was the only applicant.

So at 25 I flew to Otago University in Dunedin, where I was enrolled in a shortened medical degree program and also started a combined 3-year specialty degree in oral surgery. I was transferred to the Christchurch Medical School the following year, and with my new girlfriend (now wife) beside me, over the next 4 years I continued to study undergraduate medicine part-time and extracted a lot of teeth, fixed broken jaws, and learned the Kiwi public hospital version of surgically working alongside orthodontists. New Zealand style.

I was 29 when I eventually graduated from both programs. I was a dental surgeon, I was a medical doctor, and now I was a Kiwi version of an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. I was also now married to a Kiwi and had a firstborn Kiwi daughter.

I wanted to return to Australia, so we packed up and headed home. After 2 years of certifying my New Zealand medical degree in Australia, I knew I needed just a couple more years of dedicated jaw surgery mentorship. Not wanting to pursue further training in the United Kingdom, luckily I received an offer from the Singapore General Hospital to work in a private-public capacity under Dr Raymond Peck Hong Lian, a British-trained maxillofacial surgeon. He was to become my final teacher. After almost 2 years of constant operating in this vestige of England surrounded by Asia, I came to practically learn everything there was then to know about corrective jaw surgery. Singapore style.

Sixteen years after starting my training in dentistry, I had completed my Australian specialty qualification in maxillofacial surgery (the FRACDS-OMS) and opened my private specialty office shortly thereafter in Newcastle, Australia. Mostly I extracted diseased teeth for dentists and perfectly good teeth for orthodontists. As it is for most maxillofacial surgeons worldwide, the majority of those teeth were crowded premolars and impacted third molars. Slowly, as confidence grew among my referring orthodontists, a small trickle of corrective jaw surgery cases came through my doors too.

Today my private practice is almost entirely derived from corrective jaw surgery. I now rarely extract teeth.

REFERRAL MODEL FOR CORRECTIVE JAW SURGERY

Because orthognathic surgery is rare, and because it is basically used only following failed specialist orthodontics, the general professional dental view of orthognathic surgery is mostly negative. There is little dental understanding of what corrective jaw surgery is. Rather than seeing orthognathic surgery as being therapeutic, medical, necessary, or something of high reliability or functionality, a referral for orthognathic surgery is often discouraged by the dentist as an unnecessary and highly risky extreme. This pervasive dental view that reduces all forms of jaw surgery to a limited role of only removing teeth means that orthognathic surgery is extremely rare. In all practicality, and regardless of training, most oral and maxillofacial surgeons are reduced only to the role of an oral surgeon.

Few private surgeons practically or routinely offer corrective jaw surgery procedures because orthognathic surgery is seen as secondary to orthodontics. The teeth are always corrected first, followed reluctantly by the jaws.

Rather than seeing orthognathic surgery as being therapeutic, medical, necessary, or something of high reliability or functionality, a referral for orthognathic surgery is often discouraged by the dentist as an unnecessary and highly risky extreme.

In all of my training, I was taught that orthognathic surgery was based upon a pragmatic premise of performing to what an orthodontist wanted. There was simply no other source of referral. And to an enormous degree, this repeat stream of action-reaction generated a master-servant relationship. Orthodontists literally fed oral surgery practices, albeit with dental extractions and mostly impacted third molars, and to a much smaller degree with remedial orthognathic surgery when extraction-based orthodontics simply didn’t work. To run a successful surgical business, I had to fundamentally believe in the orthodontic interpretation of everything to do with impacted and crowded teeth and in the primacy of orthodontists being the first to treat, examine, and interpret.

The major problem with this model, however, is that it traditionally ignores the face and the airway.

MY FIRST ORTHODONTIC EXPERIENCE

When I was 13 years old, my impacted canine tooth erupted extremely high behind my upper lip, and my mother recognized that it would never spontaneously be normal. In 1957, her 14-year-old sister had had an impacted and badly erupted canine removed on the advice of her orthodontist, and at 76 years old my Aunty Pam still complains bitterly of its effects on the symmetry and attractiveness of her face. As a surgical nurse trained at Sydney Hospital in Macquarie Street, my mother resolved in 1982 that her sister’s fate would not also befall me, so she took me to a highly recommended Macquarie Street orthodontic specialist in Sydney.

He advised against my mother’s proposal that expanding my maxilla would allow enough room to easily fit all my crooked teeth. He also said it was fanciful to believe that stimulating my maxilla to expand would somehow correct the underbite I was developing. He believed her proposal very controversial, impractical, and unfeasible. He further explained that I had a very flat middle face, that my cheekbones were naturally small, and that extracting the canine would indeed be a terrible idea and make the whole appearance of my face worse. I remember feeling very ugly.

My father was very skeptical about removing four perfectly good premolar teeth in order to orthodontically bring down a single impacted canine tooth. It was at this point that my mother asked if there was any way to surgically bring my maxilla forward. She suggested that this would improve my facial proportions and possibly make my nasal breathing better.

You see it was no coincidence that on this same famous Sydney street worked my allergist, who every month would give me a needle against my dust mite allergy. Further down in another building was my respiratory specialist who treated my chronic asthma. Next door to that was the ENT surgeon who had removed my tonsils when I was 4 years old. And of course there was also my pediatrician who tried to help me grow normally despite my early recurrent croup, ongoing throat infections, stuffy nose, bad bite, crooked teeth, low energy, chronic snoring, and everything else.

Читать дальше