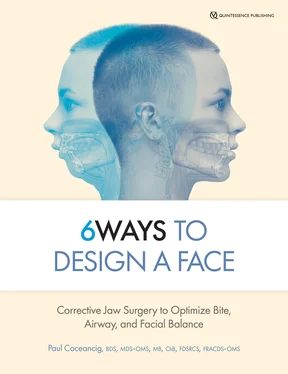

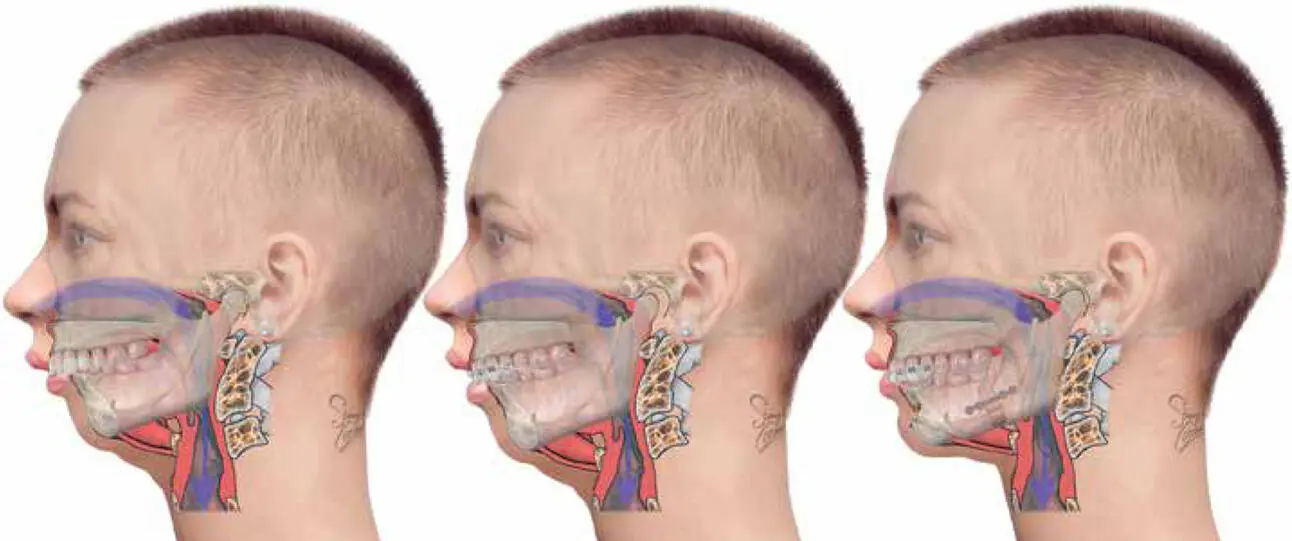

From a total of 32 teeth, and following classical orthodontic treatment for dental crowding, the end result will almost never be 32 teeth. The end result will be 28, 26, or 24 teeth. If you lose four premolars and four third molars, these lost eight “back” teeth represent a certain loss of occlusal table and dental volume, not to mention upward of ~33% loss in total dental mass ( Fig 1-8). These lost teeth will also not develop associated alveolar bone or gingiva to support them, and they will not support the face that surrounds them.

FIG 1-8 Extraction-based orthodontics of Class I dental crowding in adolescence. Four premolar extractions are a staple of almost all orthodontic practice. The third molar impactions that almost inevitably co-arise will eventually lead to a consideration of their extraction, premised on an idea of them being redundant or unnecessary. But removing eight teeth leads to a ~33% reduction in dental mass. In assessing only the bite, there is no assessment of the face or future adult airway. Forward planning toward how the adult face will look—after the orthodontics is completed—is entirely ignored.

Non-jaw surgeons may empiricize that corrective jaw surgery is invasive. But what equal professional rationalism exists to explain or accept that permanently removing one-third of a child’s dental mass through a combination of classical orthodontics and traditional oral surgery is not considered invasive? In my view, traditional orthodontics inherently relies upon invasiveness and is quite the opposite of conservative.

Nevertheless, this competition between ideas of conservatism, easiness, or invasiveness only considers the teeth. Are there other things we are ignoring by insisting on focusing and diminishing our diagnosis or treatments to the teeth alone? In demonizing the other professional, it’s easy to ignore what we do not know or see or talk about, or worse, what we refuse to acknowledge.

NONDENTAL CONSEQUENCES OF TRADITIONAL LEAD-ORTHODONTICS

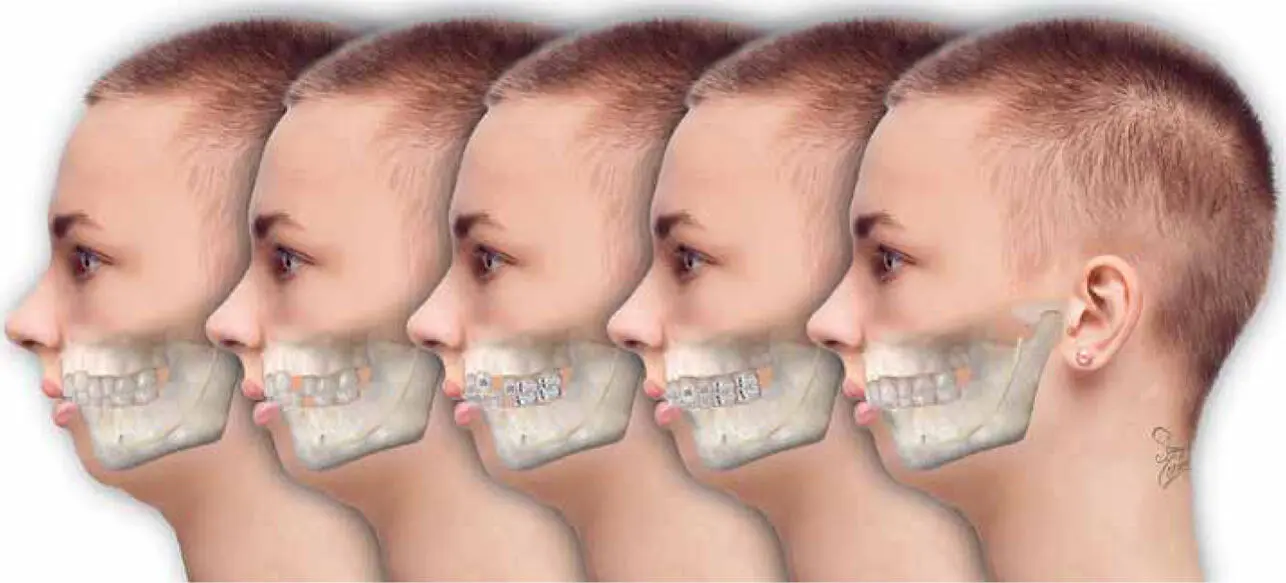

Lead-orthodontics is what I call treatment where orthodontics comes first. The orthodontist is the first to assess the bad bite and the dental crowding. Everything that follows is as a consequence of the orthodontic event that preceded it, or of the orthodontic assessment, or of the orthodontic diagnosis. The entire conversation revolves around the orthodontic management of teeth ( Figs 1-9and 1-10).

FIG 1-9 In treating without orthodontic extractions, traditional lead-orthodontics for Class II, division 1 malocclusion aims to attempt some retraction of the maxillary anterior teeth. A vertical gumminess results, with parted lips, accentuated by the lack of chin often associated with anterior mandibular hypoplasia (AMHypo). Orthodontic retraction (Class II) elastics also train the patient to hold the mandible forward while awake. After the impacted third molars are removed, the lip incompetence and chronic forward jaw posturing can be relieved with a small advancement bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) into a Class I bite, with upward sliding genioplasty to improve lip seal. This basic form of jaw correction surgery is always and only done under the primary direction and recommendation of the treating orthodontist, and almost always with current orthodontics in place in order to help “settle the bite.” Because the geniohyoid is not greatly stretched or advanced by either the sliding genioplasty or the small BSSO, there is only a small advancement of the airway—certainly not to a degree that would permanently overcome the total effect of glossoptosis or future risk of developing OSA.

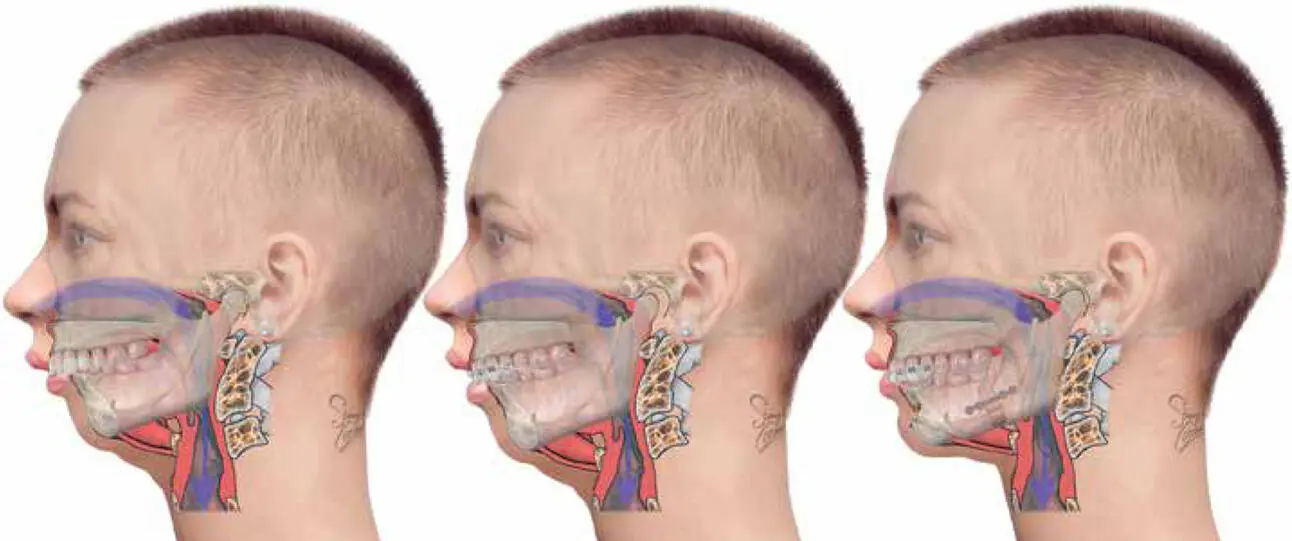

FIG 1-10 By their constraining effect and pull-back on the maxilla, all jaw splints, including MyoBrace, TwinBlock, Herbst, and Frankel, will partially “correct” the maxillary anterior tooth prominence of Class II malocclusion, but this effect is entirely by restricting growth of the maxilla, by pulling the maxillary anterior teeth backward and downward, and by positioning the mandible forward during waking hours. As a Cochrane review demonstrates, 1there is no proof that jaw splints will grow a child’s small mandible or act any differently to any other form of camouflage orthodontics. MyoBrace offers no scientific support for their marketing and therapeutic claims that they “grow the small mandible.” At night, the supine child, adolescent, or adult will fall asleep, and as conscious tone is lost, the tongue and jaw will completely relax backward to obstruct the airway, thus reversing any daytime influence of such presumed tongue training and awake forward jaw posturing. The eventual effect of all camouflage nonextraction orthodontic therapies for Class II is therefore the same—to shrink the maxilla, produce a gummy smile, and help train the adolescent to hold the mandible forward, but only when awake.

As a maxillofacial surgeon, I clinically see three broad age groups of people. The first group are adolescents (10–21 years old) with a full complement of crowded adult teeth and a bad bite looking to keep everything and in a perfect face, forever. The second group are adults (22–49 years old) unhappy with the gummy smiles and cosmetic facial disproportions they attribute to camouflage orthodontics. And finally there is the middle-aged group (50+ years) with a history of orthodontics and dental extractions who now snore and have thick necks and uncontrollable weight gain. In reality these three groups are really the same people, with the same anatomical conditions, just at different stages of their lives.

For every person with a bad bite, there are three combined, interwoven, inseparable treatment considerations: occlusion, airway, face.

This book explains how each of these groups can be managed with one overlying simple clinical philosophy, and that is to include a surgical treatment from the start. The jaw surgeon has never not been part of the equation of the treatment of bad bites. Likewise, it is not possible to ignore or delete orthodontics from that equation either. But the relationship between the two sides must be reinterpreted to correctly solve it. As I will come to elaborate in this book, orthodontics and oral surgery go hand in hand. They developed together from the start. Whether I operate on jaws to remove third molars or operate on jaws to fundamentally fix jaw size, the operations are fundamentally the same, and they are performed almost the same way, and with a similar collaborative orthodontic effort. All that changes is primacy.

Maxillofacial surgeons are the absolute and only experts in facial disease and of facial abnormality and skeletal facial issues, all of which are associated with bad bites, crowded teeth, airways, and of course the face. The maxillofacial surgeon still needs orthodontics, but the relationship has changed. The roles have swapped.

For every person with a bad bite, there are three combined, interwoven, inseparable treatment considerations: occlusion, airway, face.

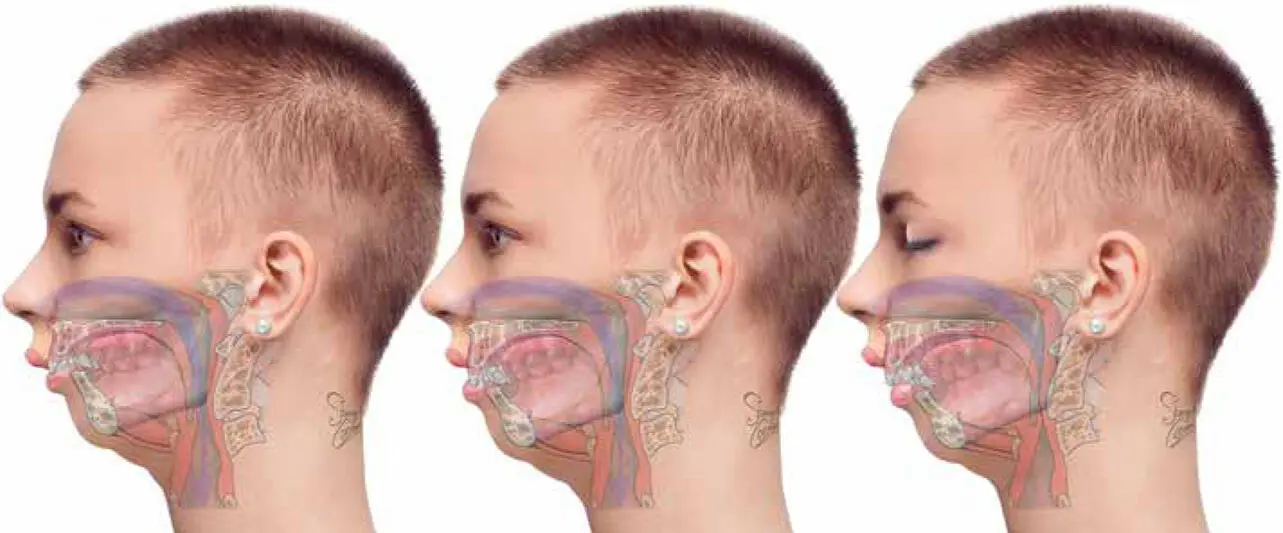

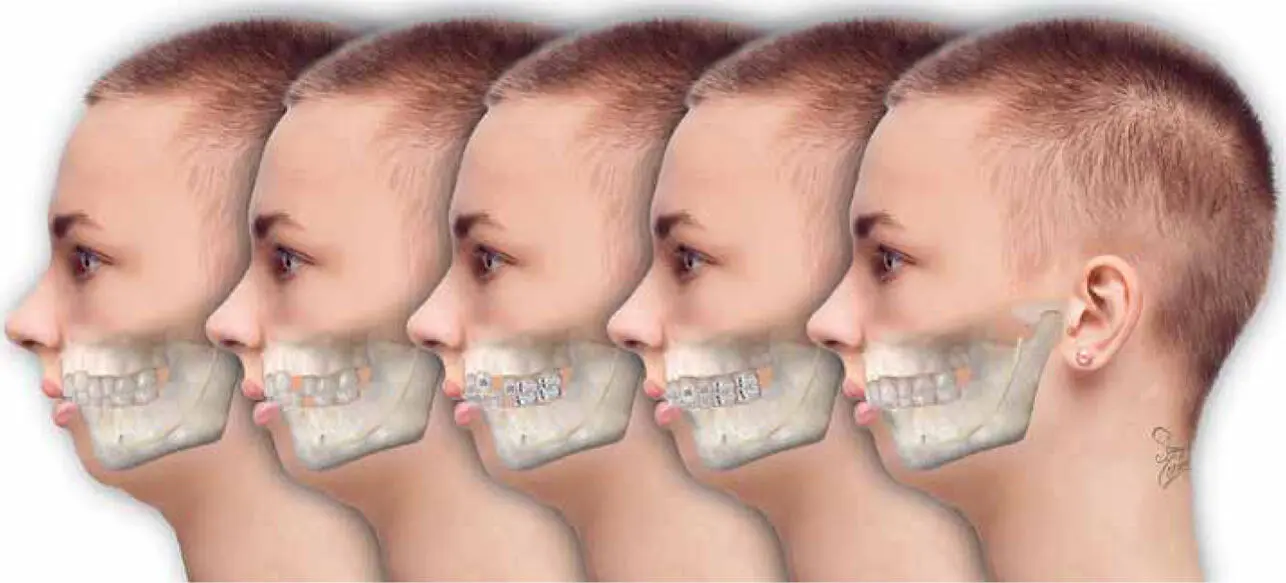

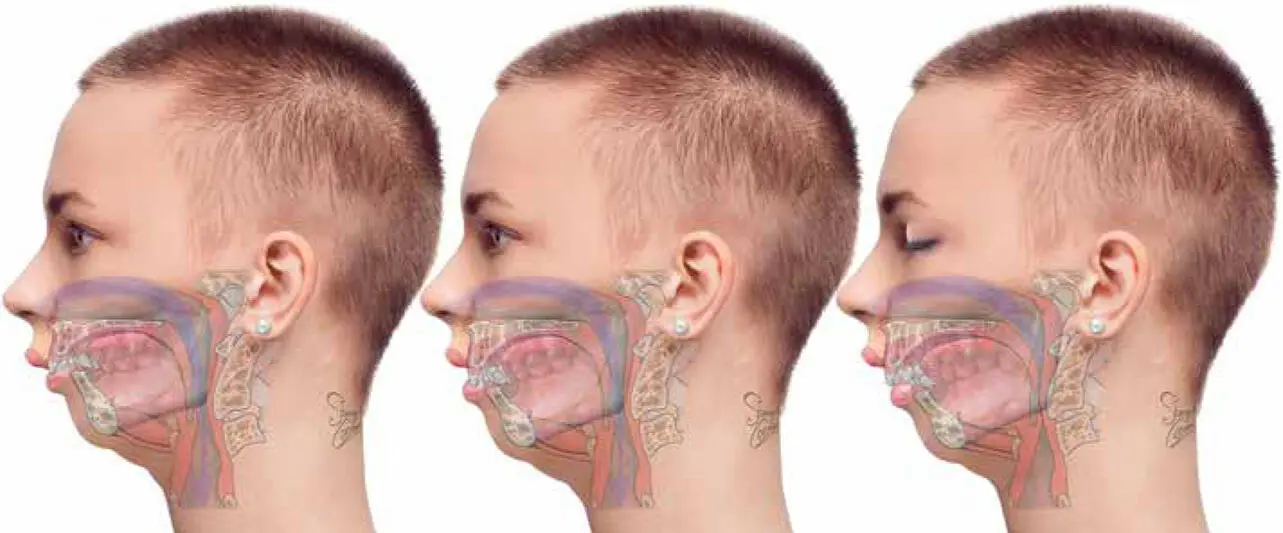

OUR ILLUSTRATIONS

In order to properly compare all the treatment types and ideas of anatomical derangement that lead to malocclusion, and in order to make meaningful assessments of the effects of treatments on facial proportions and airways and across ages, this book uses a single model—an imaginary female as she transitions through life. In the 7th century Pythagoras described six ages of man: infancy (0–6 years), adolescence (7–21 years), adulthood (22–49 years), middle age (50–62 years), old age (63–79 years), and advanced age (80+ years). This book illustrates the model at three of these ages ( Fig 1-11): infancy (around age 2 years), adolescence (around age 17 years), and old age (around age 65 years). Throughout the book you will see only her relaxed facial profile with teeth together, both awake and asleep.

Читать дальше