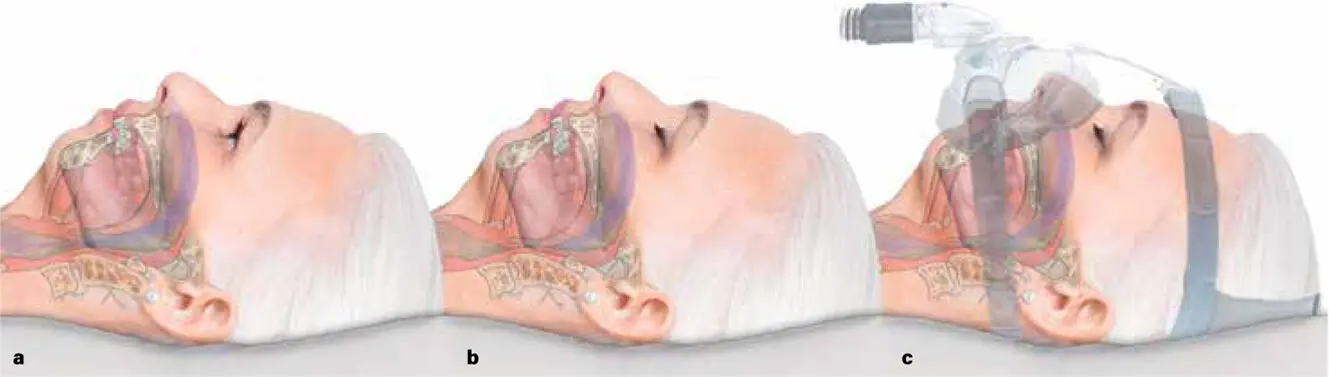

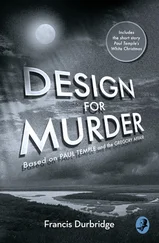

All a person needs is two things. The first is a mask and a machine that can deliver continuous positive airway pressure via the nose and mouth ( Fig 2-4). This is called a CPAP device.

FIG 2-4 (a) Lying awake, the tongue has enough tone to resist gravity, and the retroglossal airway is patent. (b) With deepening sleep, there is a loss of tongue tone, and under gravity the retroglossal airway collapses—producing airway obstruction—and apnea occurs. (c) A positive increase in airway pressure using CPAP can partially overcome retroglossal airway collapse for most (but not all) people. Mathematically, CPAP works best up to the horn torus, but not past the horn torus.

The second thing is personal tolerance. Without tolerance, a person with OSA will not be able to use a CPAP machine for 8 hours a night, every night, for the rest of their life.

CPAP THERAPY

The effectiveness of CPAP therapy is measured by the AHI score through repeat sleep studies. The practical effective goal of CPAP is to reduce the AHI score by reducing the average number of apnea or hypopnea episodes per hour a person suffers while they are asleep.

However, CPAP does NOT reverse hypertension, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, or stroke risk. And, more importantly, CPAP does not cure a person of OSA. CPAP will never give anyone a permanent AHI of 0 because, fundamentally, a sleep study does not acknowledge or eliminate the reasons why OSA is happening in the first place.

CPAP does NOT reverse hypertension, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, or stroke risk. And, more importantly, CPAP does not cure a person of OSA.

SYMPTOMS AND COMPLAINTS OF OSA

Ironically, the very same complaints that often bring the patient to the clinic for testing are not measurable or primary goals of CPAP therapy—things like getting a better night’s sleep or feeling better during the day.

A person’s set of symptoms and complaints may be wide, and they may even seem oddly disconnected to OSA or to each other. They can include insomnia in bed—they may be having an arousal as they fall asleep lying on their back—while somehow easily falling asleep at their desk with their head forward over a book. General anxiety and depression is commonly reported, as is poor concentration or poor work or scholastic performance. There may be specific complaints, seemingly unrelated to each other, such as muscle soreness, neck problems, recurrent headaches, or teeth grinding or jaw clenching or TMJ problems. People can complain of general fatigue, poor sports participation, general unfitness, and maybe even more general problems such as vague stomachache, irritable bowels, general muscle pain, restless legs, or chronic tiredness. And they may complain of ongoing weight gain that is almost impossible to control, slow down, or reverse.

All of these personal concerns are not measured or reported in a sleep study. And these complaints are not reflected in an AHI score either. Even though they may be considered effects or associations of OSA, whether they go away or not using CPAP is unpredictable and unmeasurable.

MAD THERAPY

Another treatment option for OSA offered by sleep dentists is the MAD, or mandibular advancement device ( Fig 2-5). The MAD helps to hold the mandible and back of the tongue forward and may help with breathing at night ( Fig 2-6). Like CPAP, the effect of the MAD can be measured by an AHI score, and the sleep physician may suggest a MAD if CPAP does not seem to be tolerable for their patient.

FIG 2-5 For some patients, the CPAP can be intolerable. Also, with extensive obstruction, CPAP pressures may not be enough to overcome airway collapse. The only other device that has been shown to provide a known and objective (nonsurgical) improvement to the AHI score, and possibly also to other symptoms, is the MAD. These dental splints are given a range of different proprietary names and are marketed on a broad range of therapeutic claims or comfort levels. But all of them are variations of Pierre Robin’s original Monobloc invention. The one main advantage of the MAD is that by activating the wedge and screw in the top appliance, it can incrementally extend the mandible forward. In achieving symptomatic relief, and a reduction of AHI score, it is possible to ascertain the distance that jaw surgery may need to permanently overcome to open the collapsed nighttime airway.

FIG 2-6 (a) Lying awake, the tongue has enough tone to resist gravity, and the retroglossal airway is patent. (b) With deepening sleep, there is a loss of tongue tone, and under gravity the retroglossal airway collapses—producing airway obstruction—and apnea occurs. (c) Opening the mouth and advancing the mandible pulls the hyoid and epiglottis forward (the lower part of the C3ERPO column), but only allows for oral breathing to occur. The MAD is far more effective at opening the closed torus surrounding the obstructed airway than the CPAP device. Unlike CPAP, the MAD does not allow for nasal airflow to occur. Successful use of a MAD to relieve someone of OSA absolutely confirms the presence of glossoptosis.

Just like CPAP, the MAD is also not a permanent cure for OSA, and it may or may not assist in addressing daytime symptoms and complaints. Unlike CPAP, however, a MAD can only enable oral breathing, not nasal breathing. And, unlike CPAP use, which really does not have any secondary side effects apart from intolerance, the MAD can lead to significant TMJ issues such as pain, joint clicking, and jaw muscle discomfort. Because the MAD holds the whole bite and mandible forward, chronically it can also lead to permanent negative effects on a person’s bite and normal chewing patterns.

How body fat aggravates OSA

Obesity is seen so often with snoring and OSA that it is casually seen as causative. We also see OSA occurring in people who have thick muscular necks, such as weight lifters. This common association of obesity, thick necks, increased intra-abdominal fat, and older age—and the simple fact that we see OSA so rarely in people who have thin necks and who are generally skinny—means we assume that being fat is the cause of snoring and OSA.

However, these co-observations of obesity and OSA reflect more of an association, or at best an aggravation. The association between the two is not true causation. There are many people who are fundamentally skinny, and young, and who still have upper airway collapse. What really causes OSA is far more fundamental and detailed than a simple blame upon obesity. That being said, it is absolutely true that weight reduction can eliminate OSA, but only where weight gain caused and fueled and aggravated the full end-point expression of OSA to finally occur.

When considering how obesity aggravates OSA, it is helpful to imagine the neck as essentially a donut ( Fig 2-7). As fat is deposited under the skin and around the intestines, so too does fat thicken the neck and constrict the soft flabby tissues that surround the upper airway. As the donut gets bigger, the hole in the middle gets smaller. If the hole was already small to begin with, the donut doesn’t need to get much bigger before the inside hole doesn’t exist anymore. When the hole just pinches, this is called a horn torus . As neck thickening advances, the inner hole closes more and more, until the donut achieves the shape of a sphere. A patent torus can be given a value > 1, meaning airway passage is absolute. A horn torus, where the inner hourglass airway has just pinched, has a value of 1. A perfect sphere has a value of 0. Between 1 and 0 is the mathematic chance that a CPAP or MAD has the ability to regain the inner hole and regain nighttime airflow.

Читать дальше