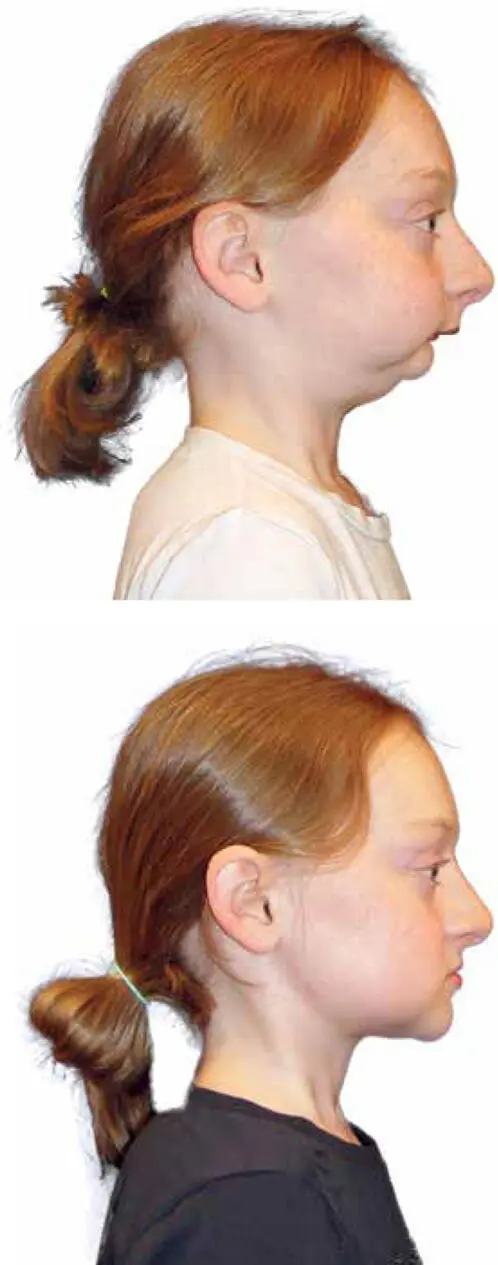

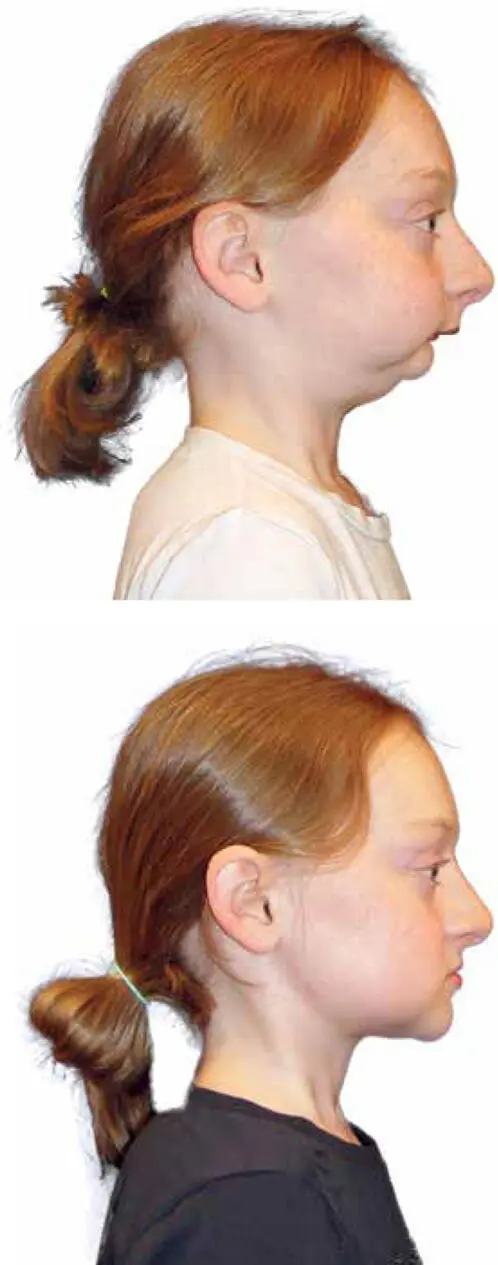

FIG 2-1 Before and after photographs (taken 6 weeks apart) of a 12-year-old adolescent girl with severe mandibular hypoplasia (caused by Melnick-Needles syndrome; see Fig 8-1) associated with snoring and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Weighing only 51 pounds, this patient’s small size reflects the scientific evidence that SDB has significant negative effects on growth hormone (GH) assay and associated growth retardation. Early adolescent treatment by modern jaw surgery correction methods such as intermolar mandibular distraction osteogenesis (IMDO) have clear benefit.

I am 52 years old as I write this, and behind me lies a professional lifetime of treating small jaws, treating the effects of small jaws, and avoiding the effects of small jaws. As a maxillofacial surgeon, I offer a perspective that is not as a sleep dentist offering a mandibular advancement device (MAD), a throat surgeon offering uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), an otolaryngologist prescribing tonsillectomy, a craniofacial surgeon treating a neonate with jaw distraction, an orthodontist offering braces, an oral surgeon recommending tooth extraction, a psychiatrist prescribing amphetamines to a sleepy schoolchild, or a respiratory physician offering a sleep study and a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device.

As a maxillofacial surgeon, my training is as a dentist, an oral surgeon, a bite specialist, a general medical doctor, and as a primary medical-surgical specialist in corrective jaw surgery.

I can stretch a small jaw, and with it I stretch out the tongue behind it, the face in front of it, and the spaces between the crowded teeth as well. I have particular insight into these issues because I suffer from the same diseases that I treat. But how do my surgical therapies also medically treat my patients? What are my overall therapeutic aims?

MY JOURNEY WITH OSA

I was innately skinny as a young adult and adolescent. Until I was 28 years old I weighed only 150 pounds and had a body mass index (BMI) of 21, with only about 5% body fat. I always had mildly small jaws (see Introduction), but I never snored. I was just a mouth breather drooling silently into my pillow.

As my active young adult life increasingly became settled, my children were born, and work started to dominate my life, I sat more, exercised less, socialized with more dinners, traveled in planes, and lived in more hotels. So I started putting on weight. My new external environment eventually gained a new equilibrium, and internally my equilibrium changed to suit. I put on more muscle. I was physically stronger. But I was also putting on much more fat too.

By the time I was 34 years old, I was up to 174 pounds with a BMI of 25. When I hit 42, I weighed 209 pounds and my BMI was 30. By 51, I was almost 245 pounds, and my BMI was a shocking 35. My fasting blood glucose, which should have been below 5.5, was now 6.0. My fasting insulin, which should have been 8.0 at most, was now 11. My knees and ankles hurt when I walked. I was grumpy. After plane trips my ankles swelled. My wardrobe was a museum of thin to fat.

In the 8 years previous, I had successfully tried four diets, each of which lasted a year and brought me down to 165 pounds, but something always stopped the momentum, and my weight would return to a newer and bigger number. And if I plotted these new weights (y) on an age (x) scale, they fell on the one straight line.

What was happening was that I could not change my environment, and I could not permanently keep a low weight to suit that environment. I still worked at the same job. I still had the same social world, the same town that surrounded me. The same kids, the same food, the same supermarket, the same kitchen, the same subtle pressures. So when you combined everything into one big ball of different-colored strings, it all really meant I just lived in the same inflexible universe of modern human life.

My weight was essentially an end-point expression of my internal balance point. My internal equilibrium was always reverting back to the same point that was defined by the static equilibrium that surrounded me. And I was aging. And everything was getting unnoticeably and slowly worse. It was all so subtle. But what really woke me up was when I started snoring. Literally.

It’s a horrible feeling. The choking. And it would force me to suddenly sit up, trying to catch my breath. And I’d stay propped up with pillows scared to fall asleep again. I put on a home monitor, and it gave me an AHI score around 5. Not much. My phone had an app that recorded how well I slept. It wasn’t good. Another app recorded my snoring sounds. It sounded like a freight train. More frightening was when I fully obstructed, and I wasn’t breathing at all.

I woke up tired. My thoughts were muddled. I spontaneously fell asleep. Everywhere. In movies. Watching TV. Lying in the grass under a tree. My mood changed too. I was less patient. Maybe I was more curmudgeonly. So I had bariatric surgery, and had almost 90% of a very large stomach permanently removed. It is called a “gastric sleeve.” The weight loss was dramatic and relentless and permanent. By 212 pounds my snoring had stopped, and my old shirts started fitting around my neck. At 198 pounds my blood glucose and fasting insulin levels were completely normal. My blood pressure returned to 120/70. By 165 pounds I was completely healthy again. I wasn’t hungry at all, and I easily maintained small meals. My ankles were normal. My knees worked normally. And of course I was sleeping fully, my dreams returned, my emotional balance was regained, and my thinking restored.

I couldn’t change the equilibrium of my external world, so I forced permanent change on my own internal equilibrium. Even as surgeons, we are all dependent consumers on our own craft and colleagues.

SNORING AND DENTISTRY

Snoring has an enormous impact on people and society. Sleeping partners are the first affected, and eventually our bodies too start telling us that something’s wrong ( Fig 2-2). The health effects of poor sleep, including poor rapid eye movement (REM) cycles, chronic hypoxia, hypocognition, cardiovascular hypertension, and of course obesity, bleed into our personal lives, and this has become a real problem for society at large. When seen across a lifetime, the individual and economic effects of SDB make snoring a major health crisis that has real effects across the world economy.

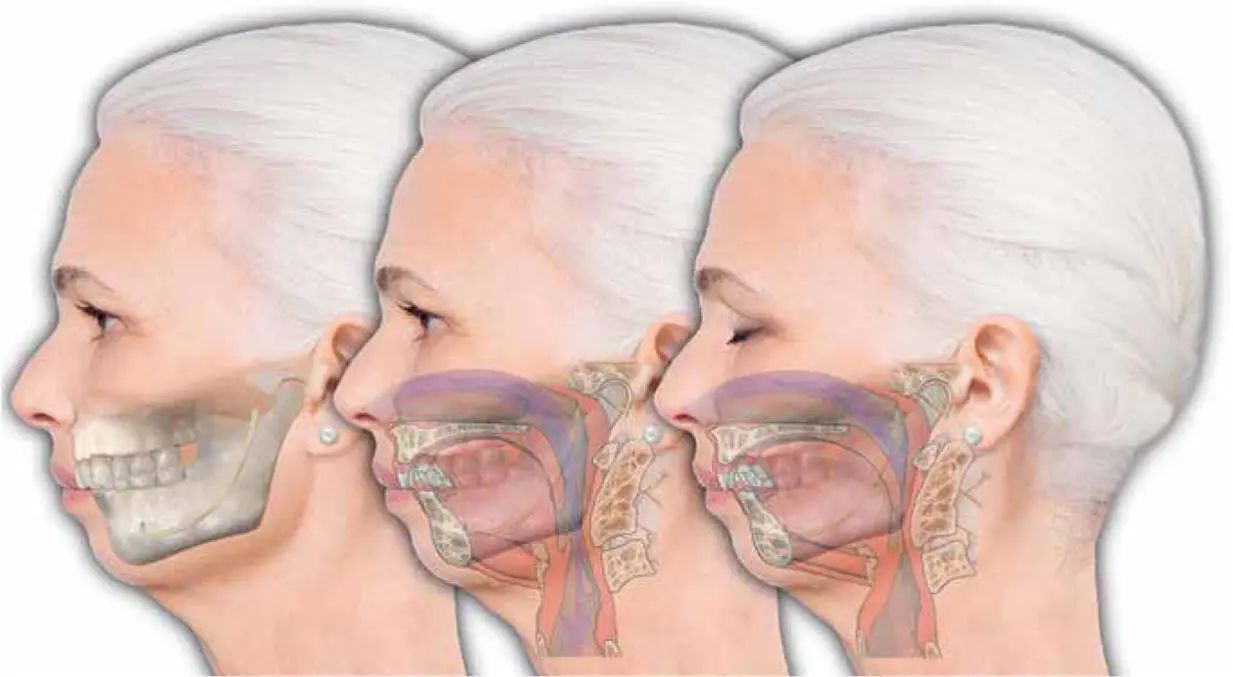

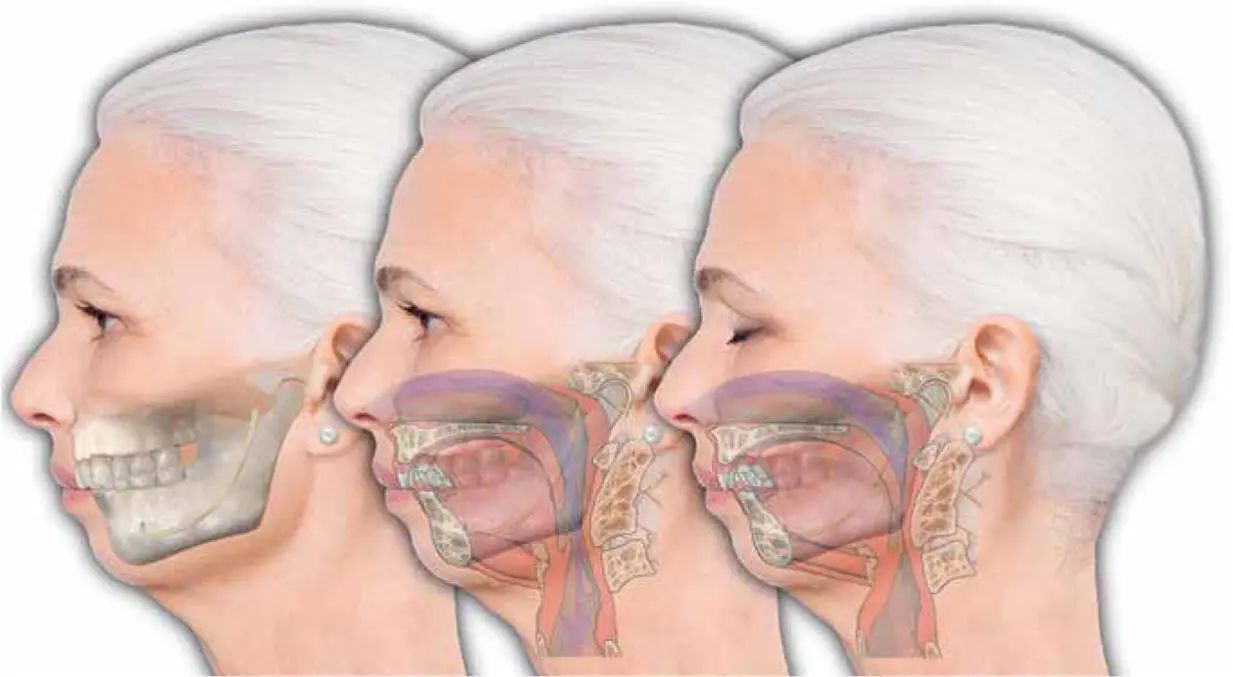

FIG 2-2 The symptom of snoring coupled with an AHI score from a sleep study ignores completely the anatomical reasons underlying why the patient has recurrent apnea episodes during sleep. Our faces are so much a part of the consideration of personal identity that we forget that faces are functional objects. A person born with a small mandible relative to the rest of their body will always have that disproportion as their body ages. Overbites, camouflage orthodontics, big tonsils, and eventually OSA are all part of the same life journey that many of us travel.

Snoring causes lethargy. Poor sleep translates into reduced cognition and reduced physical activity. Snoring has a direct effect on every facet of the way each of us performs, lives, and remains healthy. While we can see the direct day-to-day effects of a poor night’s sleep, in the long term, snoring’s effects are cumulative—and relentless.

In 1923, Pierre Robin was the first person in the world to relate dentistry to snoring. While we associate Pierre Robin syndrome (and the micromandible) to his name, what he actually described were three things. First, Robin recognized that at least 40% of all Europeans (he was a Parisian dentist) had small mandibles. He called this condition mandibular hypoplasia. Second, Robin observed that all people with a small mandible snored. He saw the effect of a collapsed tongue on the back of the throat and gave the condition a name—glossoptosis. Third, Robin developed a jaw splint to hold the mandible forward, and with it the back of the tongue. The use of the device was life-changing for patients who suffered from breathing difficulty at night. Pierre Robin called this invention the Monobloc. It lives on today, with little recognition of his profound ideas, in the form of modern orthodontic MADs.

Читать дальше