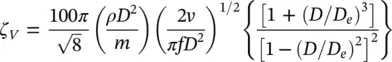

(2‐15)

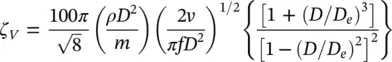

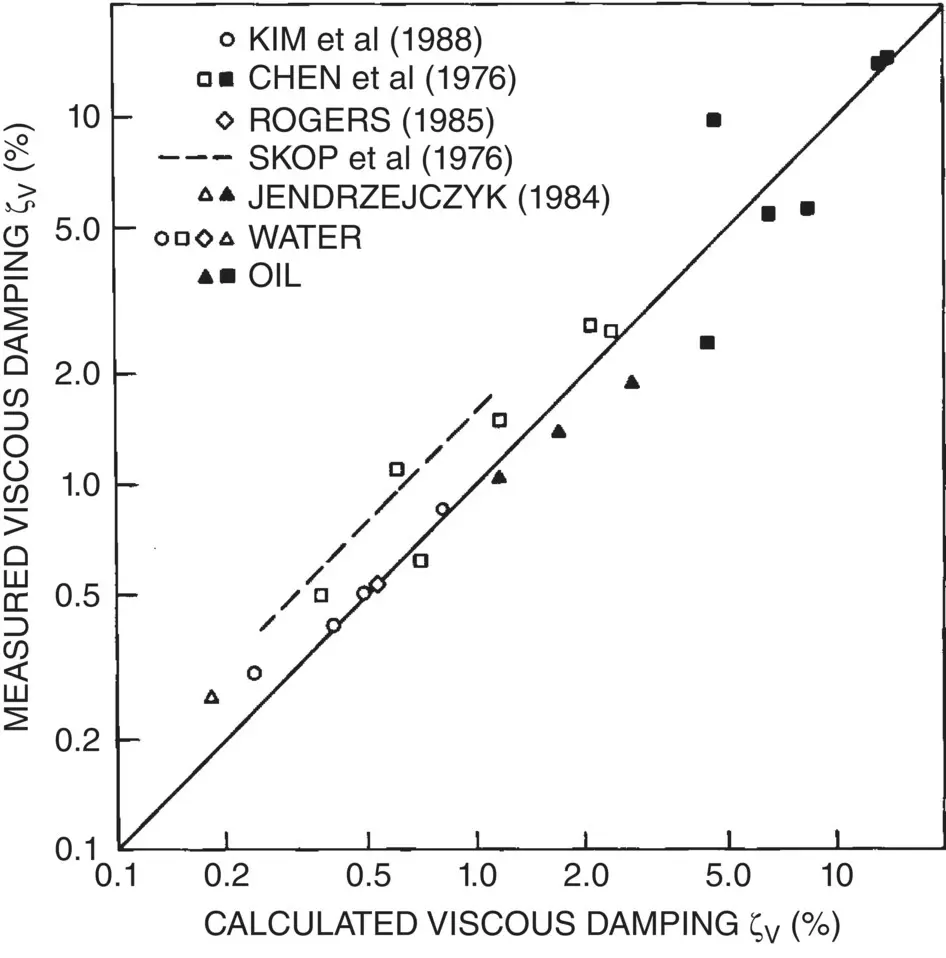

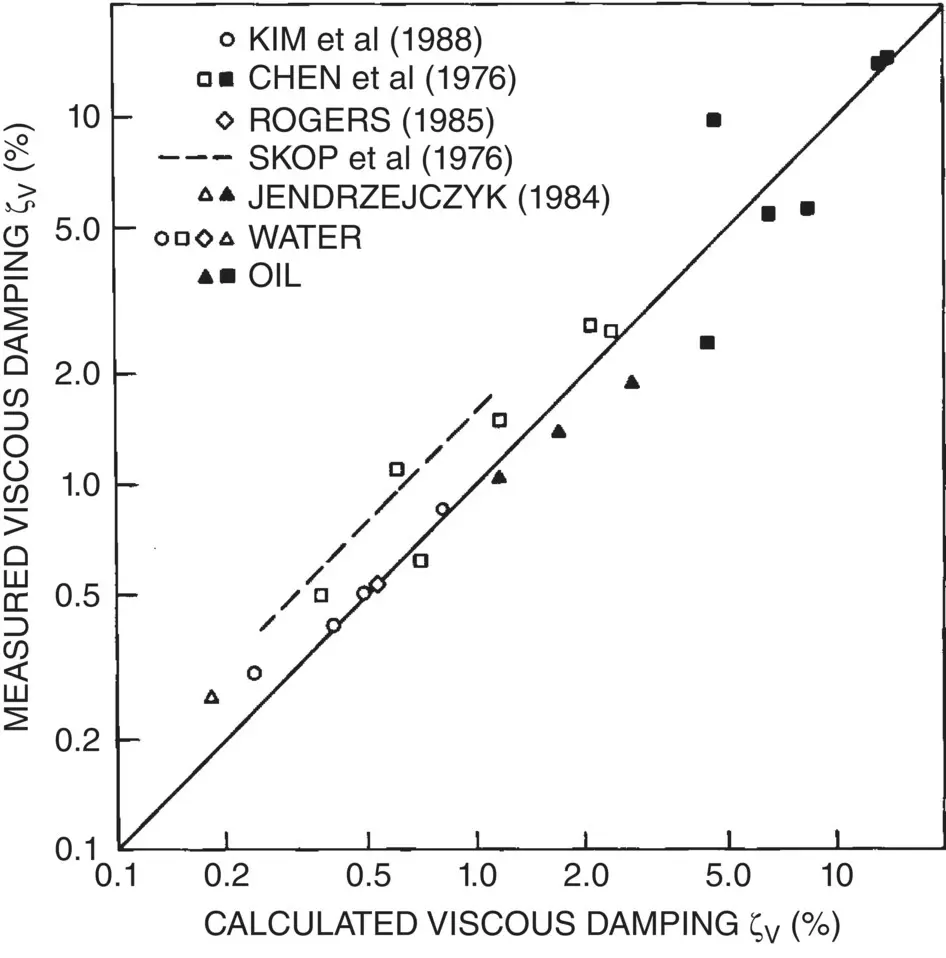

where v is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid and f is the natural frequency of the tube for the mode being analysed. Clearly, viscous damping is frequency dependent. Calculated values of damping using Eq. (2-15)are compared against experimental data in Fig. 2-7. The comparison shows reasonable agreement.

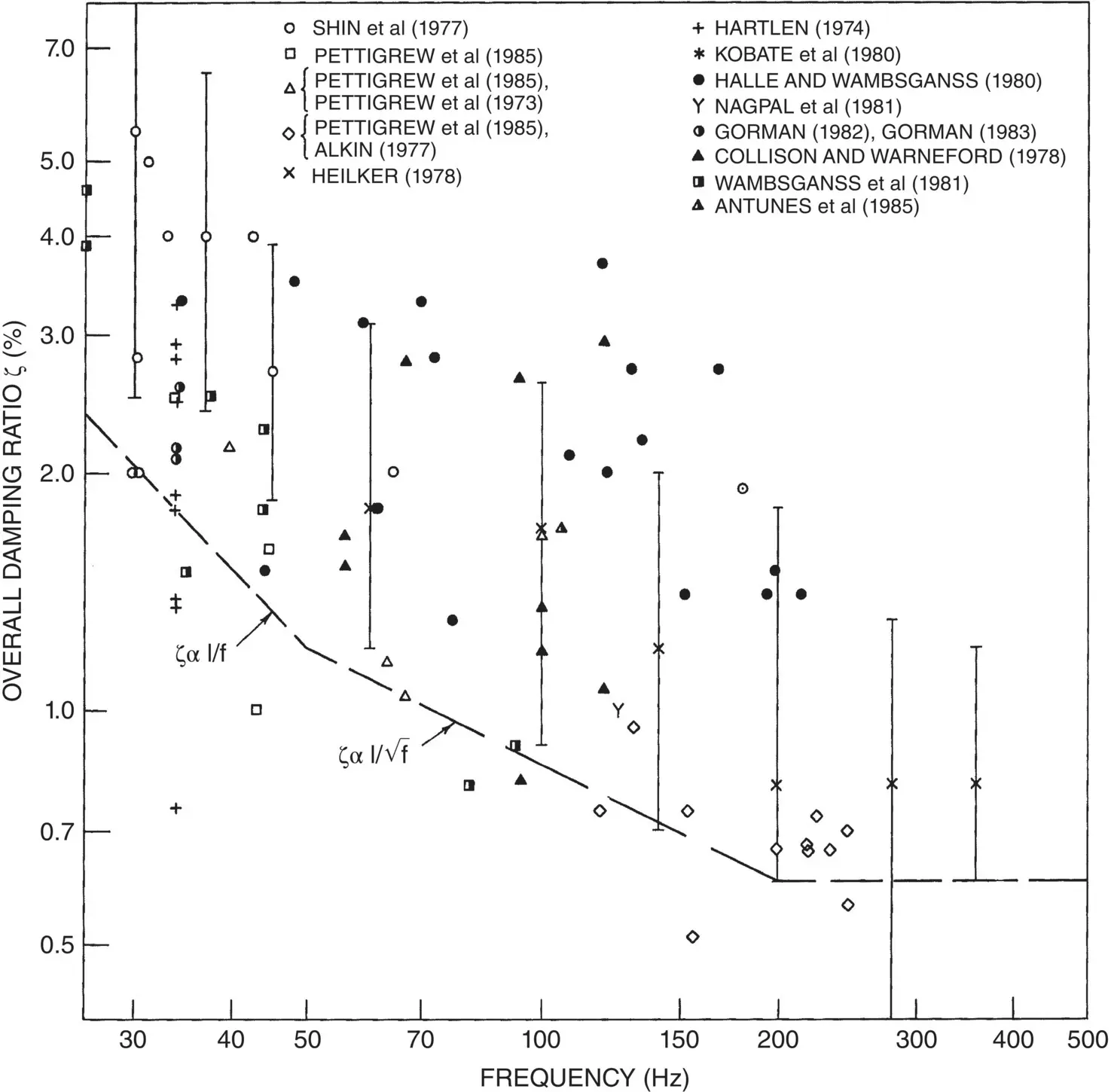

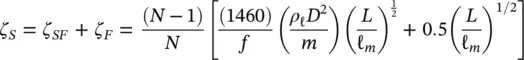

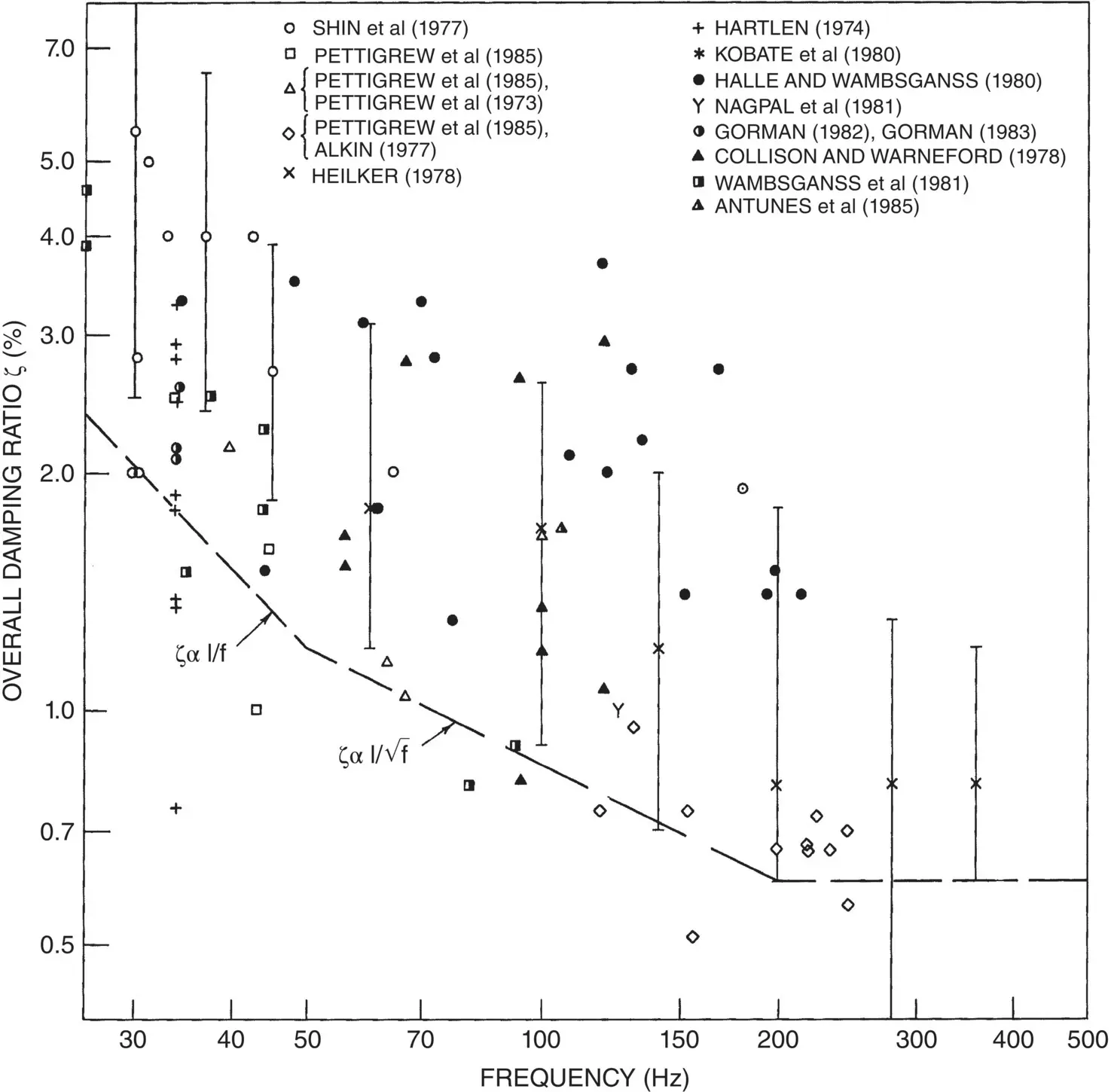

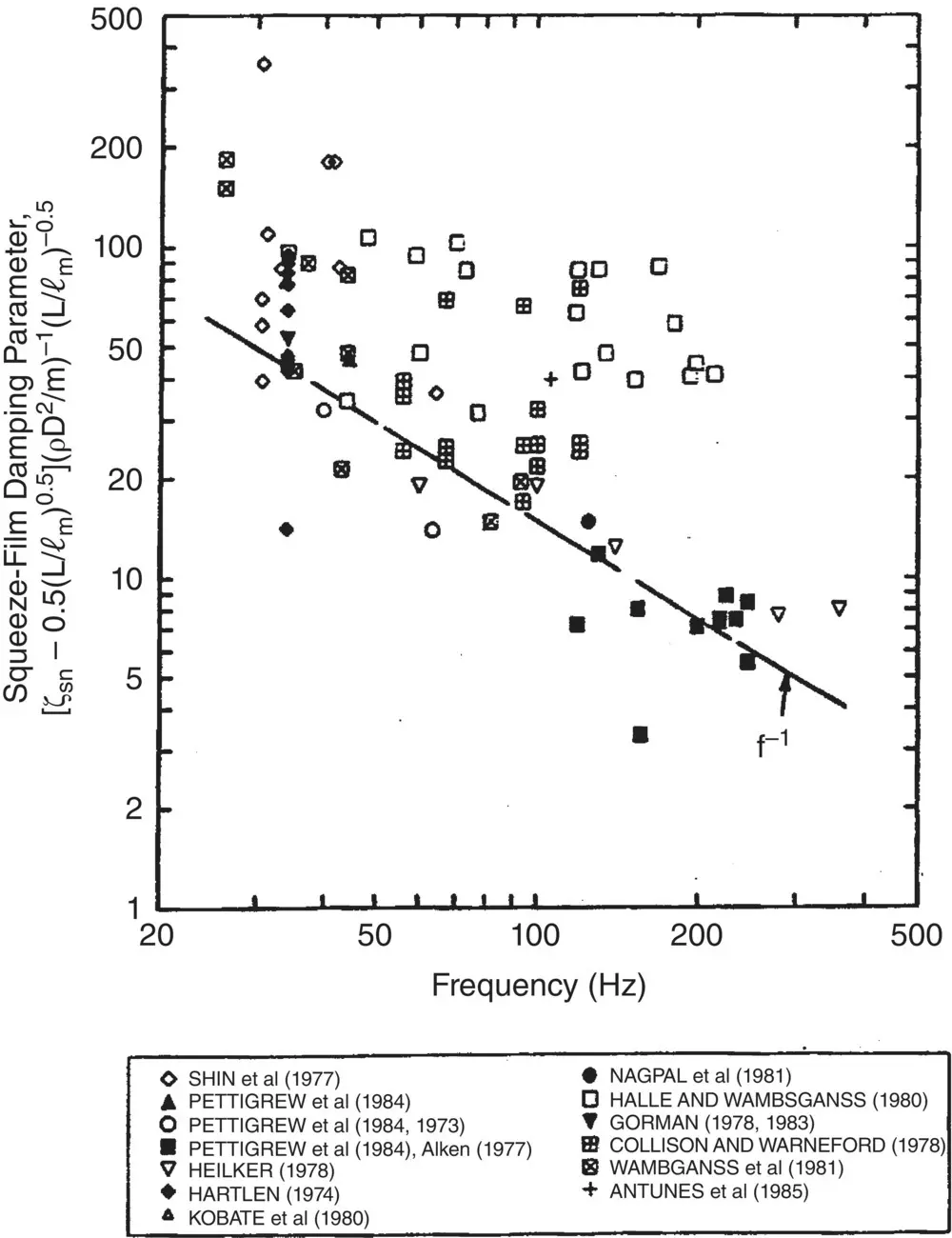

Squeeze‐film damping, ζ SF, and friction damping, ζ F, take place at the supports. Semi‐empirical expressions were developed, based on available experimental data, to formulate friction and squeeze‐film damping as discussed by Pettigrew et al (2011) and in Chapter 5. The available experimental data is outlined in Fig. 2-8. Thus, squeeze‐film damping (in percent) may be formulated by

(2‐16)

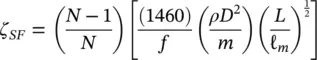

and friction damping (in percent) by

(2‐17)

where ( N − 1)/ N takes into account the ratio of the number of supports over the number of spans, L is the support thickness and ℓ mis a characteristic tube length. The latter is defined as the average of the three longest spans when the lowest modes and the longest spans dominate the vibration response. This is usually the case. When higher modes and shorter spans govern the vibration response, then, the characteristic span length should be based on these shorter spans. This could happen when there are high flow velocities locally, such as in entrance or exit regions.

Fig. 2-7 Viscous Damping Data for a Cylinder in Unconfined and Confined Liquids: Comparison Between Theory and Experiment.

Fig. 2-8 Damping Data for Multi‐Span Heat Exchanger Tubes in Water.

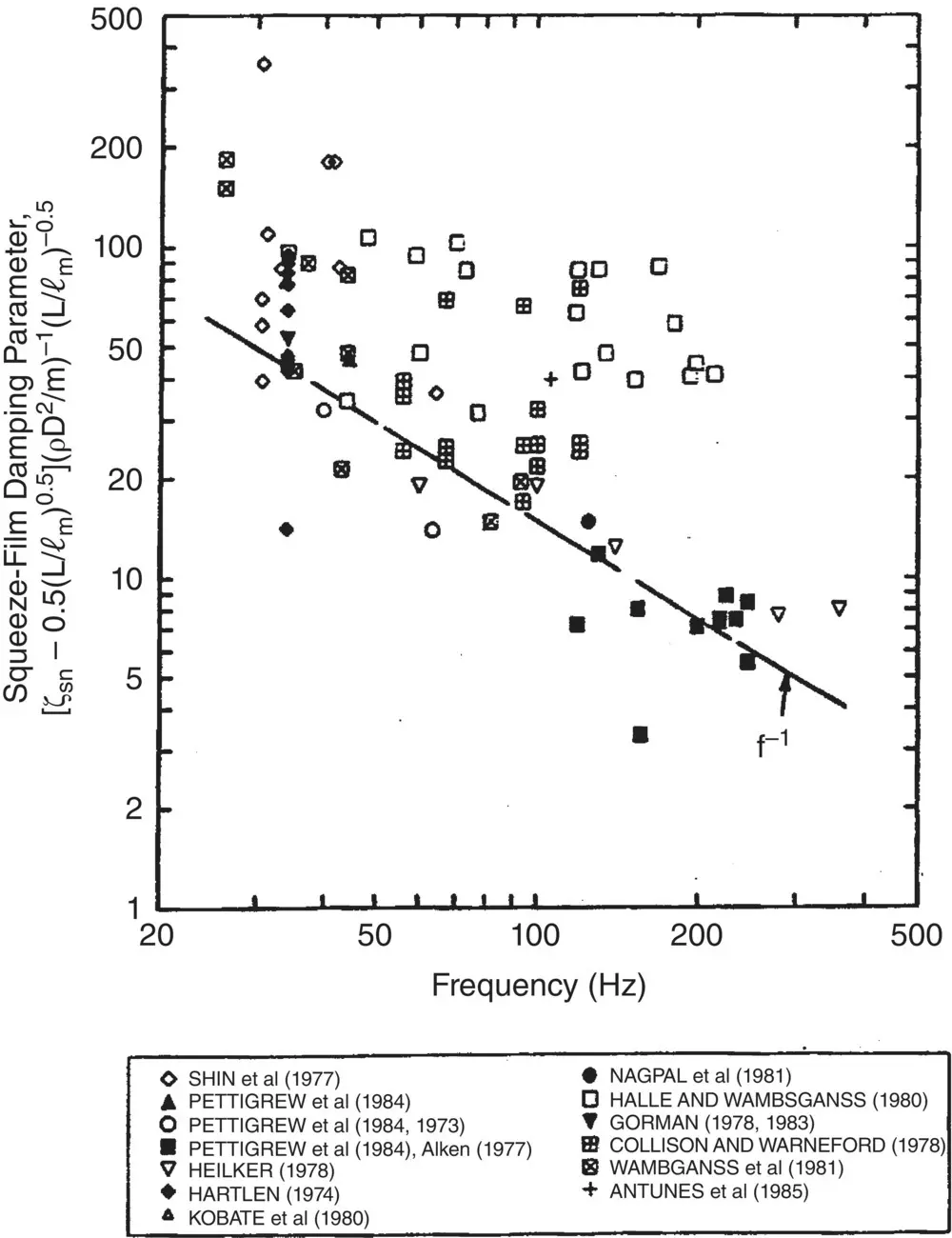

Fig. 2-9 Comparison Between Tube Support Damping Model (Squeeze‐Film and Friction) and Experimental Data.

Equations (2-16)and (2-17)are combined to determine the squeeze‐film damping parameter, 1460/ f , and compared against available experimental data in Fig. 2-9. There is large scatter in the data, which is mostly due to the nature of the problem. Heat exchanger tube damping depends on parameters that are difficult to control, such as support alignment, tube straightness, relative position of tube within the support, and side loads. These parameters are statistical in nature and probably contribute to much of the scatter. A conservative but realistic criterion for damping is obtained by taking damping values at roughly the lower decile of the available data, as shown in Fig. 2-8.

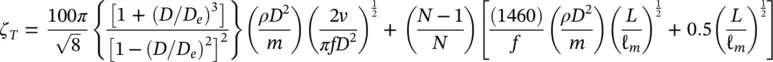

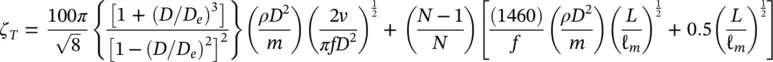

Substituting Eqs. (2-15), (2-16)and (2-17)in Eq. (2-14):

(2‐18)

Although somewhat speculative, Eq. (2-18)formulates all important energy dissipation mechanisms and fits the data best. Thus, it is our recommendation as a damping criterion for design purposes.

However, if the damping ratio predicted by this equation is less than 0.6%, we recommend taking a minimum value of 0.6%. As shown in Fig. 2-8, a minimum damping of 0.6% appears reasonable. In Fig. 2-8, there is no experimental data for frequencies below 25 Hz. Rather than extrapolating Eq. 2-18to lower frequencies, we recommend using a maximum total damping of 5%.

Damping in Two‐Phase Flow

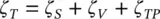

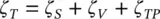

The subject of heat exchanger tube damping in two‐phase flow was reviewed by Pettigrew and Taylor (1997) as discussed in Chapter 6. The total damping ratio, ζ T, of a multi‐span heat exchanger tube in two‐phase flow comprises support damping, ζ S, viscous damping, ζ V, and two‐phase damping, ζ TP:

(2‐19)

Depending on the thermalhydraulic conditions (i.e., heat flux, void fraction, flow, etc.), the supports may be dry or wet. If the supports are dry, which is more likely for high heat flux and very high void fraction, only friction damping takes place. Support damping in this case is analogous to damping of heat exchanger tubes in gases, Pettigrew et al (1986). Damping due to friction (and impact) in dry supports may be expressed by Eq. (2-13). The above situation is unlikely in well‐designed recirculating steam generators. However, it could exist in some areas of once‐through steam generators.

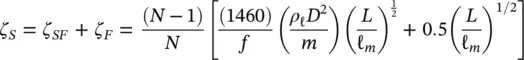

When there is liquid between the tube and the support, support damping includes both squeeze‐film damping, ζ SF, and friction damping, ζ F. This situation is analogous to heat exchanger tubes in liquids and the support damping may be evaluated with Eqs. (2.18) and (2.19) above:

(2‐20)

Note that in Eq. (2-20), ρ ℓis the density of the liquid within the tube support, whereas m is the total mass per unit length of the tube including the hydrodynamic mass calculated with the two‐phase homogeneous density.

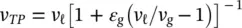

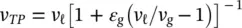

Viscous damping in two‐phase mixtures is analogous to viscous damping in single‐phase fluids (Pettigrew and Taylor, 1997). Homogeneous properties of the two‐phase mixture are used in its formulation, as follows:

(2‐21)

where v TPis the equivalent two‐phase kinematic viscosity as per McAdams et al (1942):

(2‐22)

Above 40% void fraction, viscous damping is generally small and could be neglected for the U‐bend region of steam generators. However, it is significant for lower void fractions.

There is a two‐phase component of damping in addition to viscous damping. As discussed by Pettigrew and Taylor (1997) and in Chapter 6, two‐phase damping is strongly dependent on void fraction, fluid properties and flow regimes, directly related to confinement and the ratio of hydrodynamic mass over tube mass, and weakly related to frequency, mass flux or flow velocity, and tube bundle configuration. A semi‐empirical expression was developed from the available experimental data to formulate the two‐phase component of damping, ζ TP, in percent:

Читать дальше