A dangerous alternative emerges. Either this legitimate mistrust of environmentalism leads to the neglect of the dangers of environmental devastations of the Earth. Ecological struggles would then be a matter of “white utopia,” or at the very least unimportant when faced with the immense task of reclaiming dignity. 38Or, paradoxically, in their laudable calls for ecological sensitivity, postcolonial thinkers such as Dipesh Chakrabarty and Souleymane Bachir Diagne will have discarded their critical theoretical tools and adopted the same environmentalist terms, scales, and historicities, such as, for example, “global subject,” “whole Earth,” and “humanity in general.” 39The durability of the psychological, socio-political, and ecosystemic violence and toxicity of the “ruins of empires” is concealed. 40Likewise, one underestimates the colonial ecology of racial ontologies that always links the racialized and the colonized to those psychic, physical, and socio-political spaces that are the world’s holds. This is true whether it is a matter of the spaces of legal and political non-representation (the enslaved), the spaces of non-being (the Negro), the spaces of the absence of logos, history, or culture (the savage), the spaces of the non-human (the animal), the spaces of the inhuman (the monster, the beast), the spaces of the non-living (camps and necropolises), or, if it is a matter of geographical locations (Africa, the Americas, Asia, Oceania), of habitat zones (ghettos, suburbs) or of ecosystems subject to capitalist production (slave ships, tropical plantations, factories, mines, prisons). In turn, the importance of ecological and non-human concerns within (post)colonial struggles for equality and dignity remain understated. Fracture .

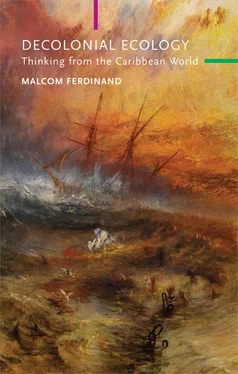

Here is the double fracture. One either questions the environmental fracture on the condition that the silence of modernity’s colonial fracture, its misogynistic slavery, and its racisms are maintained , or one deconstructs the colonial fracture on the condition that its ecological issues are abandoned . Yet, by leaving aside the colonial question, ecologists and green activists overlook the fact that both historical colonization and contemporary structural racism are at the center of destructive ways of inhabiting the Earth. Leaving aside the environmental and animal questions, antiracist and postcolonial movements miss the forms of violence that exacerbate the domination of the enslaved, the colonized, and racialized women. As a result of this double fracture, Noah’s Ark is established as an appropriate political metaphor for the Earth and the world in the face of the ecological tempest, locking the cries for a common world at the bottom of modernity’s hold.

The slave ship or modernity’s hold

In order to heal this double fracture, my second proposition takes the Caribbean world as the scene of ecological thinking. Why the Caribbean? Firstly, because it was here that the Old World and the New World were first knotted together in an attempt to make the Earth and the world into one and the same totality. Eye of modernity’s hurricane, the Caribbean is that center where the sunny lull was wrongly confused for paradise, the fixed point of a global acceleration sucking up African villages, Amerindian societies, and European sails. This “Caribbean world” therefore concentrates experiences of the world that range from colonial and enslaving histories to the underside of modernity, histories which are not limited to the geographical boundaries of the Caribbean basin. This gesture is a response to the absence of these Caribbean experiences within those ecological discourses that nevertheless claim to question the same modernity. While researchers have been interested in the ecological consequences of colonization in the Caribbean and North America, the consequences of global warming, and contemporary environmental politics, the Caribbean is most often seen as the place for experimenting with concepts that come from somewhere else. 41The colonial gaze is maintained by the scholar who departs from the Global North and carries in his suitcase concepts that are to be experimented with in a non-scholarly Caribbean, before he leaves again with the fruits of this new knowledge, now capable of prescribing the way forward. Such an approach hides the imperial conditions that allowed, in the Caribbean and other colonial spaces, the development of sciences such as botany, the emergence of forest conservation management, 42and the genesis of the concept of biodiversity, 43and ignores the other forms of knowledge concerning the environment and the body that were already there. 44Above all, one would miss those Caribbean ecologists who go “beyond sand and sun” by holding together social justice, antiracism, and ecosystem preservation. 45

A contrario , I embrace the Caribbean world as a scene of ecological thinking. Thinking ecology from the perspective of the Caribbean world proposes an epistemic shift in the conceptualizations of the world and the Earth at the heart of ecology , meaning that there is a change of scene from which discourses and knowledge are produced. Instead of the scene of a free, educated, and well-to-do White man wandering the countryside of Georgia like John Muir, or in the forest of Montmorency like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, or around Walden’s pond like Henry David Thoreau, I suggest another scene that took place historically at the same time: one of violence inflicted upon men and women in slavery, dominated socially and politically inside the holds of slave ships. North–South power relations, racisms, historical and modern slavery, the resentments, fears, and hopes that constitute the experience of the world, are placed at the heart of the ship where the ecological tempest is seen and confronted.

Within a binary understanding of modernity, one that opposes nature and culture, colonists and indigenous people, this proposition instead highlights the experiences of modernity’s third terms . 46I am referring to those who were dismissed when, in the sixteenth century, the priest Bartolomé de Las Casas, famous in the Valladolid controversy of 1550, defended the Amerindians against the Spanish conquerors with an appeal that was accompanied by repeated suggestions to “stock up” in Africa and develop triangular trade. 47Neither modern nor indigenous, more than 12.5 million Africans were uprooted from their lands from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century. Hundreds of millions of people were enslaved and kept for centuries in an off-ground [ hors-sol ] relationship to the Americas. 48Over and above the social conditions of the colonial enslaved, they were also considered “Negroes,” object-beings of a political and scientific racism that indexes them to an inextricable immanence with nature or to an unsurpassable pathological irresponsibility. However, the so-called Negroes also developed relationships with nature, ecumenes, ways of relating to non-humans, and ways of representing the world to themselves. It so happens that these ideas and practices were marked by slavery, by the experience of transshipment in the Atlantic slave trade, and by political and social discrimination for several centuries in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. 49Yes, there is also an ecology of the enslaved, of those transshipped in the European trade, an ecology that maintains continuities with the indigenous African and Amerindian communities but is not reducible to either of them. 50An ecology that was forged in modernity’s hold: a decolonial ecology .

Decolonial ecology articulates the confrontation of contemporary ecological issues through an emancipation from the colonial fracture, by rising up from the slave ship’s hold . The urgency of the struggle against both global warming and the pollution of the Earth is intertwined with the urgency of political, epistemic, scientific, legal, and philosophical struggles to dismantle the colonial structures of living together and the ways of inhabiting the Earth that still maintain the domination of racialized people, particularly women, in modernity’s hold. This decolonial ecology is inspired by the decolonial thinking that was begun by a group of Latin American researchers and activists, such as Anibal Quijano, Arturo Escobar, Catherine Walks, and Walter Mignolo, who were and are working to dismantle an understanding of power, knowledge, and Being that has been inherited from colonial modernity and its racial categories. They emphasize those other ways of thinking that emerge from “the spaces that have been silenced, repressed, demonized, devaluated by the triumphant chant of self-promoting modern epistemology, politics, and economy and its internal dissensions.” 51

Читать дальше