The poisoning of the water supply of Flint, Michigan, in 2014, 1which resulted from the austerity-motivated switch to the Flint River for the city’s water, was clearly linked to capitalist industrialization on land historically stewarded by the Ojibwe. The trajectory that led from the production of carriages to the emergence of the automobile industry with no regard to the deleterious environmental changes included, among other developments, the pollution of the Flint River, especially by General Motors, which is why the river had not been previously considered as a source of water. However, under conditions of austerity, the switch from the Detroit River to the Flint River unleashed a cascade of issues, including the dislodging of lead from the pipes transporting water to the Flint community, where the majority of residents are Black and where over 40 percent live below the poverty line. Revealingly, even before the impact of the lead on the children of Flint was acknowledged, General Motors petitioned to switch back to the Detroit River because the existing supply was corroding engine parts and thus placing the profitability of the company in jeopardy. Apparently it was more important to save the automobile engines than the precious lives of Black children, whose fate recapitulated the violence directed at the Ojibwe people, who were the original inhabitants of the area where the city of Flint is located.

Flint should have been a lesson to the US and to the world that, when Black children’s lives are jeopardized by the logic of contemporary capitalism, there are so many more humans, animals, plants, water, and soil that are cavalierly relegated to the realm of collateral consequences, a term that is also used to reflect the far-reaching ravages of what we have come to call the prison industrial complex. Not long after the Flint calamity, the protests on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation demanding a halt to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline revealed that it had been redirected through the reservation in order to avoid contaminating the water of Bismarck, the capital city of North Dakota, overtly signaling that indigenous lives are inherently less valuable than white lives.

Malcom Ferdinand insists that we not understand such slogans as Indigenous Lives Matter or Black Lives Matter as simple rallying cries that, while certainly meaningful to First Nations people and people of African descent, are otherwise marginal to the project of safeguarding the planet. Instead he encourages us to recognize that the deeper meaning of these assertions is that we cannot retain whiteness and maleness as measures for liberatory futures, even when the presence of such measures is deeply hidden beneath such seductive universalisms as freedom, equality, and fraternity. He recognizes the importance of new frames, new trajectories, and new ways of imagining futures where chemical and ideological toxicities – including insecticides such as chlordecone, along with racism and misogyny – are prevented from polluting our worlds to come.

Angela Y. Davis

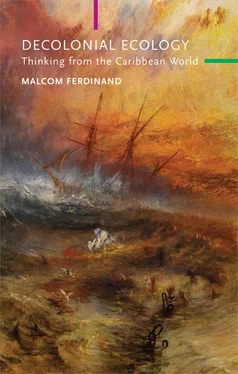

Figure 1Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On , 1840.

1 1 Laura Pulido, “Flint, Environmental Racism, and Racial Capitalism,” Capitalism Nature Socialism 27/3 (2016): 1–16; DOI: 10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013.

Prologue A Colonial and Environmental Double Fracture: The Caribbean at the Heart of the Modern Tempest

Of course, we’re only straws tossed on the raging sea … but all’s not lost, gentlemen. We just have to try to get to the eye of the storm.

Aimé Césaire

A Tempest 1

An angry red covers the sky, the waves are rough, the water is rising, the birds are panicking. Swirling winds wrap around the destruction of the Earth’s ecosystems, the enslavement of non-humans, as well as wars, social inequality, racial discrimination, and the domination of women. The sixth mass extinction of species is underway, chemical pollution is percolating into aquifers and umbilical cords, climate change is accelerating, and global justice remains iniquitous. Violence spreads through the crew, chained bodies are thrown overboard, sinking into the marine abyss, while brown hands search for hope. The skies thunder loudly: the world-ship is in the midst of a modern tempest. In the face of this storm, which finds horizons hidden behind the clouds, vision blurred by the salty waters, and cries covered up by unjust gusts, what course can be taken?

This book seeks to chart a new course through the conceptual sea of the Caribbean. For the Europeans of the sixteenth century, the word “Caribbean,” being the name of the first inhabitants of the archipelago, meant savages and cannibals. 2Like the character Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest , “Caribbean” would refer to an entity devoid of reason. The inspection of this entity by waves of European colonization and their sciences would bring forth economic profits and objective knowledge. This colonial perspective persists today in the touristic representation of the Caribbean as a place where one can take a break on the beach without people and offside to the world. To think ecology from the perspective of the Caribbean world is a reversal of this touristic perspective, driven by the conviction that Caribbean men and women speak, act, and think about the world and inhabit the Earth. 3

Many rushed to Noah’s Ark when the ecological flood was announced, with little concern for those abandoned at the dock or those enslaved within the ship. In the face of the ecological storm, saving “humanity” or “civilization” would require leaving the world ashore. This desolating perspective is revealed by the slave ship Zong off the coast of Jamaica in 1781, painted by William Turner and found on the cover of this book. At the mere thought of the storm, some are chained below deck and others are thrown overboard. Environmental collapse does not impact everyone equally and does not negate the varied social and political collapse already underway. A double fracture lingers between those who fear the ecological tempest on the horizon and those who were denied the bridge of justice long before the first gusts of wind. As the eye of the storm, the Caribbean makes it necessary to understand the storm from the perspective of modernity’s hold . Through the Caribbean’s Creole imaginary of resistance and its experiences of (post)colonial struggles, the Caribbean allows for a conceptualization of the ecological crisis that is embedded within the search for a world free of its slavery, its social violence, and its political injustice: a decolonial ecology . This decolonial ecology is a path charted aboard the world-ship towards the horizon of a common world, towards what I call a worldly-ecology . Three philosophical propositions guide the way.

Noah’s ark or the colonial and environmental double fracture

The first proposition is based on the observation of modernity’s colonial and environmental double fracture . This fracture separates the colonial history of the world from its environmental history. This can be seen in the divide between environmental and ecological movements, on the one hand, and postcolonial and antiracist movements, on the other, where both express themselves in the streets and in the universities without speaking to each other. This fracture is also revealed on a daily basis by the striking absence of Blacks and other people of color in the arenas of environmental discourse production, as well as in the theoretical tools used to conceptualize the ecological crisis. With the terms “Black people,” “Red people,” “Arabs,” or “Whites,” far from the a priori essentialization of nineteenth-century scientific anthropology, I am referring to the construction of the racist hierarchy of the West that resulted in many peoples on Earth having the condition of being associated with a race, culminating in the invention of Whites above non-Whites. 4Because of this asymmetry, I refer to those others, non-Whites, by the term “racialized,” for it is their humanity that has been and is being contested by these racial ontologies, and it is they who de facto suffer a discriminatory essentialization. 5Even though this hierarchy is a socio-political construction that no longer has any scientific value, it should not in turn lead to the denial of the ensuing social and experiential realities (for example, by refusing to name them) or the denial of their violence, including when those realities and violence take place within environmental discourses, practices, and policies. 6

Читать дальше