In the United States, a 2014 study showed that minorities remain under-represented in governmental and non-governmental environmental organizations, with the highest positions held predominately by White, educated, middle-class men. 7A similar situation exists in France. Racialized people who have come as part of colonial and postcolonial migration and who collect the cities’ garbage, clean public squares and institutions, drive buses, trams, and subway trains, the ones who serve hot meals in university dining halls, deliver mail, care for the sick in hospitals, those whose welcoming smiles at the entrance of establishments are a guarantee of security, are the same ones who are usually excluded from the university, governmental, and non-governmental arenas that focus on the state of the environment. As a result, environmental specialists regularly speak at conferences as if all these people, their stories, their suffering, and their struggles remain inconsequential to the way we think about the Earth. This leads to the absurdity that the planet’s preservation is thought about and implemented in the absence of those “without whom,” as Aimé Césaire writes, “the earth would not be the earth.” 8Either this fracture is completely hidden behind the fallacious argument that non-White peoples do not care about the environment, or it is restricted to a subject that is deemed secondary to the “real” purpose of ecology. My proposition here is that this double fracture be positioned as a central problem of the ecological crisis , thereby radically transforming its conceptual and political implications.

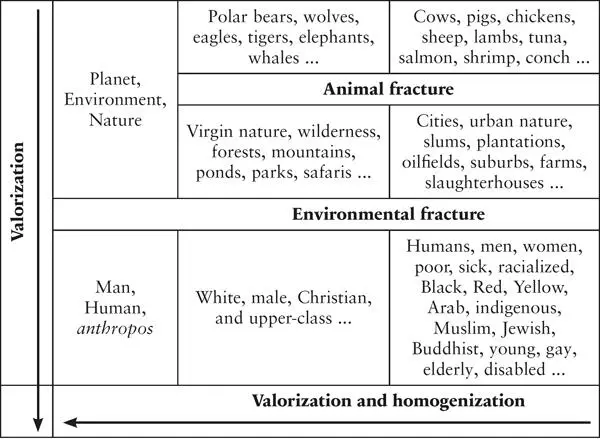

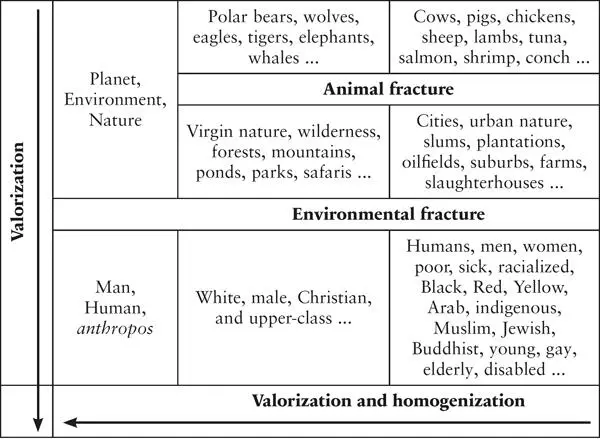

On the one hand, the environmental fracture follows from modernity’s “great divide,” those dualistic oppositions that separate nature and culture, environment and society, establishing a vertical scale of values that places “Man” above nature. 9This fracture is revealed through the technical, scientific, and economic modernizations of the mastery of nature, the effects of which can be measured by the extent of the Earth’s pollution, the loss of biodiversity, global warming, and the associated persistence of gender inequality, social misery, and the “disposable lives” that are thereby created. 10The concept of the “Anthropocene,” popularized by Paul Crutzen, winner of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, attests to the consequences of this duality. 11It refers to the new geological era that comes after the Holocene, in which human activities have become a major force impacting the Earth’s ecosystems in a lasting way. This fracture also conceals a horizontal homogenization and hides internal hierarchizations on both sides. On the one side, the terms “planet,” “nature,” or “environment” conceal the diversity of ecosystems, geographic locations, and the non-humans that constitute them. Images of lush forests, snow-capped mountains, and nature reserves mask those of urban natures, slums, and plantations. Also masked are the internal conflicts between nature conservation movements and animal welfare movements, the animal fracture , as well as the latter’s own hierarchies in which “noble” wild animals (polar bears, whales, elephants, or pandas) and pets (dogs and cats) are placed above animals that are farmed (cows, pigs, sheep, or tuna). 12On the other side, the terms “Man” or anthropos mask the plurality of human beings, featuring men and women, rich and poor, Whites and non-Whites, Christians and non-Christians, sick and healthy.

The environmental fracture

I call “environmentalism” the set of movements and currents of thought that attempt to reverse the vertical valuation of the environmental fracture but without touching the horizontal scale of values, meaning without questioning social injustices, gender discrimination, political domination, or the hierarchy of living environments and without concern for the treatment of animals on Earth. Environmentalism therefore proceeds from an apolitical genealogy of ecology comprised of its figures, like the solitary walker, and its pantheon of thinkers, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Pierre Poivre, John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, or Arne Næss. 13They are mainly White, free, solitary, upper-class men in slave-making and post-slavery societies gazing out over what is then referred to as “nature.” Despite disagreements over its definition, environmentalism remains preoccupied with “nature,” cherishing the sweet illusion that its socio-political conditions of access and its sciences might remain outside the colonial fracture. 14

Since the 1960s, some ecological movements have been concerned with addressing vertical and horizontal scales of value. Ecofeminism, social ecology, and political ecology have argued for a preservation of the environment intrinsically linked to demands for gender equality, social justice, and political emancipation. Despite their rich contributions, these green interventions make little room for racial and colonial issues. The colonial and slave-making constitution of modernity is veiled by pretentious claims to the universality of socio-economic, feminist, or juridico-political theories. In the green turn of the 1970s, arts and humanities disciplines confronted the environmental fracture while at the same time sliding the colonial divide under the rug. The absence of people of color who are experts on these issues is striking. From universities to governmental and non-governmental arenas, movements critical of the environmental fracture have marked the boundaries of a predominantly White and masculine space within postcolonial, multiethnic, and multicultural countries where the maps of the Earth and the dividing lines of the world are imagined and redrawn.

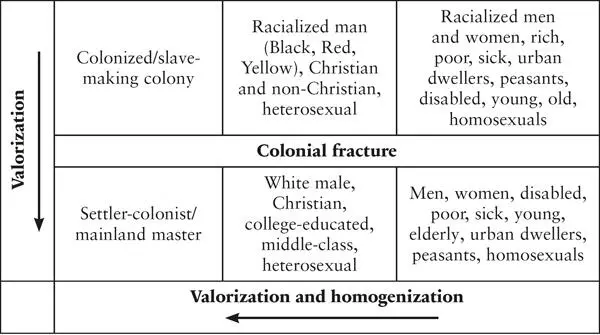

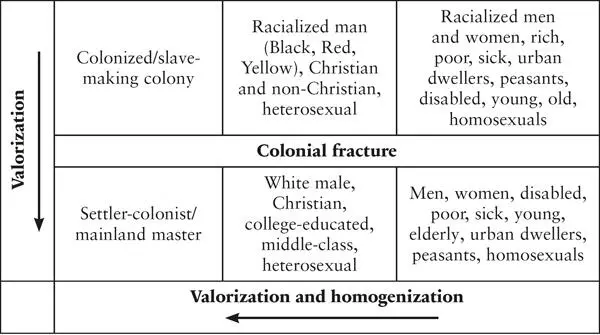

On the other hand, there is a colonial fracture sustained by the racist ideologies of the West, its religious, cultural, and ethnic Eurocentrism, and its imperial desire for enrichment, the effects of which can be seen in the enslavement of the Earth’s First Peoples, the violence inflicted on non-European women, the wars of colonial conquest, the bloody uprooting of the slave trade, the suffering of colonial slavery, the many genocides and crimes against humanity. The colonial fracture separates humans and the geographical spaces of the Earth between European colonizers and non-European colonized peoples, between Whites and non-Whites, between the masters and the enslaved, between the metropole and the colonies, between the Global North and the Global South. Going back at least to the time of the Spanish Reconquista, when Muslims were expelled from the Iberian peninsula, and the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas in 1492, this fracture places the colonist, his history and his desires at the top of the hierarchy of values and subordinates the lives and lands of the colonized or formerly colonized under him. 15In the same way, this fracture renders the colonists as homogeneous, reduces them to the experience of a White man, while at the same time reducing the experience of the colonized to that of a racialized man. Throughout the complex history of colonialism, this line has been contested by both sides and has taken different forms. 16Nevertheless, it persists today, reinforced by free markets and capitalism.

The colonial fracture

From the first acts of resistance by Amerindians and the enslaved in the fifteenth century to contemporary antiracist movements and anticolonial struggles in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, this colonial fracture is being called into question, exposing the vertical valorization of the colonized by the colonist. Anticolonialism, antislavery, and antiracism together represent the actions and currents of thought deconstructing this vertical scale of values. History has shown, however, that these movements have not always challenged the horizontal scale of values that in places maintains the relationships of domination between men and women, rich and poor, urban dwellers and peasants, Christians and non-Christians, Arabs and Blacks, among the colonized as well as among the colonists. In response, movements such as Black feminism and decolonial theory shatter both vertical and horizontal value scales, linking decolonization to the emancipation of women, recognition of different sexual orientations and different religious faiths, as well as to social justice. However, the ecological issues of the world remain relegated to the background.

Читать дальше