1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...32 Ned y Kate fueron súbditos coloniales que perdieron su apuesta por situar a la humanidad en una trayectoria distinta, una senda no tomada. Su amor mutuo formaba parte de su amor por lo común. Eros, filia y ágape encontraron su perdición en el amor maltusiano de la reproducción calculada, o ektrofeia, que está al servicio del Estado y del capital. Si recordar a Ned y Kate es decir que la ecuación blakeana, cercamiento = muerte, no tiene por qué imponerse, y si su memoria nos ayuda a afirmar la asociación entre nuestro amor por los demás y el proyecto de puesta en común, sin duda, pensé, mi investigación debía empezar con los restos de Kate.

[1]W. Blake, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Londres, 1793, p. 196.

[2]E. Despard, «Recollections of the Despard Family», 1841, Mr. and Mrs. M. H. Despard Collection «Recollections», p. 22. Véase también J. Despard, «Memoranda Connected with the Despard Family from Recollections», 1838, Mr. and Mrs. M. H. Despard Collection.

[3]A. Linklater, Measuring America: How the United States Was Shaped by the Greatest Land Sale in History, Londres, 2002.

[4]P. Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution of the Eighteenth Century: An Outline of the Beginnings of the Modern Factory System in England, Londres, 1961, p. 252.

[5]S. Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, Nueva York, 2014; E. Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, Nueva York, 2014; N. Frykman, «The Wooden World Turned Upside Down: Naval Mutinies in the Age of Atlantic Revolution», tesis doctoral, Universidad de Pittsburgh, 2010.

[6]E. Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge, 1990 [ed. cast. El gobierno de los bienes comunes. La evolución de las instituciones de acción colectiva, México, 2011]; D. Bollier, H. Silke, y Heinrich Böll Foundation (eds.), The Wealth of the Commons: A World beyond Market and State, Amherst, MA, 2012; M. Mies y V. Bennholdt-Thomsen, The Subsistence Perspective: Beyond the Globalised Economy, Londres, 1999; L. Brownhill, Land, Food, Freedom: Struggles for the Gendered Commons in Kenya, 1870 to 2007, Trenton, 2009; S. Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation, Nueva York, 2004 [ed. cast.: Caliban y la bruja. Mujeres, cuerpo y acumulación originaria, Madrid, 2010]; S. Federici, «Feminism and the Politics of the Commons in a Era of Primitive Accumulation», en C. Hughes, S. Peace, K. Van Meter y Team Colors Collective (eds.), Uses of a Whirlwind: Movement, Movements, and Contemporary Radical Currents in the United States, Edimburgo, 2010; R. Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell, the Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, Nueva York, 2009 [ed. cast.: Un paraíso en el infierno. Las extraordinarias comunidades que surgen en el desastre, Madrid, 2020]; N. Klein, «Reclaiming the Commons», New Left Review 9, mayo-junio 2001 [ed. cast.: «Reclamemos los bienes comunales», NLR 9, julio-agosto de 2001]; V. Shiva, The Violence of the Green Revolution, Londres, 1991; J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure, and Social Change in England, 1700-1820, Cambridge, 1993.

[7]G. Esteva y M. S. Prakash, Grassroots Post-Modernism, Nueva York, 1997; R. Patel, The Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy, Nueva York, 2009; L. Hyde, Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership, Nueva York, 2010; M. Hardt y A. Negri, Commonwealth, Cambridge, 2009 [ed. cast.: Commonwealth, el proyecto de una revolución del común, Madrid, 2011]; D. Graeber, Debt: The First 5.000 Years, Nueva York, 2011; H. Reid y B. Taylor, Recovering the Commons: Democracy, Place and Global Justice, Urbana, IL, 2010; D. Bollier, Silent Theft: The Private Plunder of Our Common Wealth, Nueva York, 2002; I. Boal, J. Stone, M. Watts y C. Winslow (eds.), West of Eden: Communes and Utopia in Northern California, Oakland, 2012; M. De Angelis, Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformations of Postcapitalism, Londres, 2017; G. C. Caffentzis, «On the Scottish Origin of “Civilization”», en S. Federici (ed.), Enduring Western Civilization: The Construction of the Concept of Western Civilization and Its “Others”», Westport, CT, 1995.

[8]S. Federici, Re-enchanting the Commons: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons, Oakland, 2018 [ed. cast.: Reencantar el mundo. El feminismo y la teoría de los comunes, Madrid, 2020].

[9]H. Mayhew, London Life and London Labour, Nueva York, 1968, vol. 2, p. 256.

[10]E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Nueva York, 1963 [ed. cast.: La formación de la clase obrera en Inglaterra, Madrid, 2012]; D. Worrall, Radical Culture: Discourse, Resistance and Surveillance, 1790-1820, Detroit, 1992; I. McCalman, Radical Underworld: Prophets, Revolutionaries, and Pornographers in London 1795-1840, Cambridge, 1988; M. Elliott, «The “Despard Conspiracy” Reconsidered», Past and Present 75, 1977; A. Hone, For the Cause of Truth: Radicalism in London, 1796-1821, Oxford, 1982; M. Chase, The People’s Farm: English Radical Agrarianism, 1775-1840, Londres, 2010; C. D. Conner, Colonel Despard: The Life and Times of an Anglo-Irish Rebel, Conshohocken, PA, 2000; M. Jay, The Unfortunate Colonel Despard: Hero and Traitor in Britain’s First War on Terror, Londres, 2004; R. Wells, Wretched Faces: Famine in Wartime England, 1763-1803, Gloucester, 1988.

[11]J. Zalasiewicz, A. Cearreta, P. Crutzen, E. Ellis, M. Ellis, J. Grinevald, J. McNeill, C. Poirier, S. Price, D. Richter, M. Scholes, W. Steffen, D. Vidas, C. Waters, M. Williams y A. P. Wolfe, «Response to Austin and Holbrook on “Is the Anthropocene an Issue of Stratigraphy or Pop Culture?”», Geological Society of America Groundwork 22, octubre de 2012, e21-22.

[12]S. Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonimous History, Nueva York, 1969.

[13]J.-J. Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, Londres, 1754.

[14]J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure, and Social Change in England, 1700-1820, Cambridge, 1993, p. 3.

[15]J. C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, New Haven, 2017.

[16]A Dictionary of the English Language, Londres, 1755.

[17]T. More, Utopia, Londres, 1923, pp. 43-44 [ed. cast.: Utopía, Madrid, 2011].

[18]J. Locke, Two Treatises of Government, Nueva York, 1956, p. 145.

[19]J. S. Scott, The Common Wind: Currents of Afro-American Communication in the Era of the Haitian Revolution, Londres, 2018.

[20]S. Buck-Morss, Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History, Pittsburgh, 2009, p. 60.

Primera parte

La búsqueda

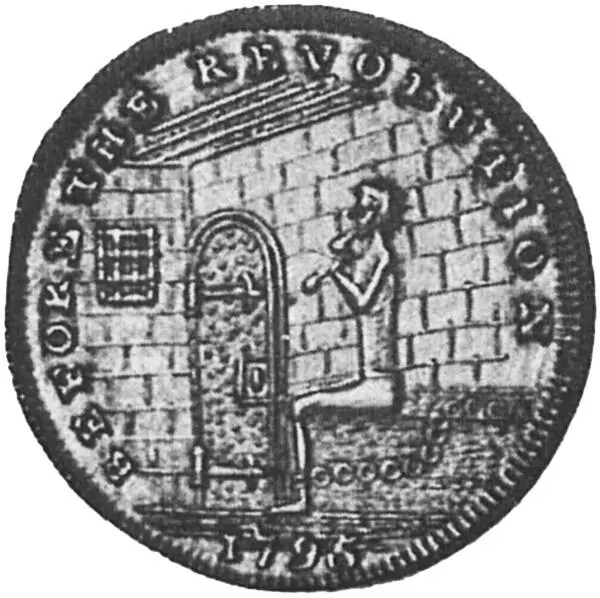

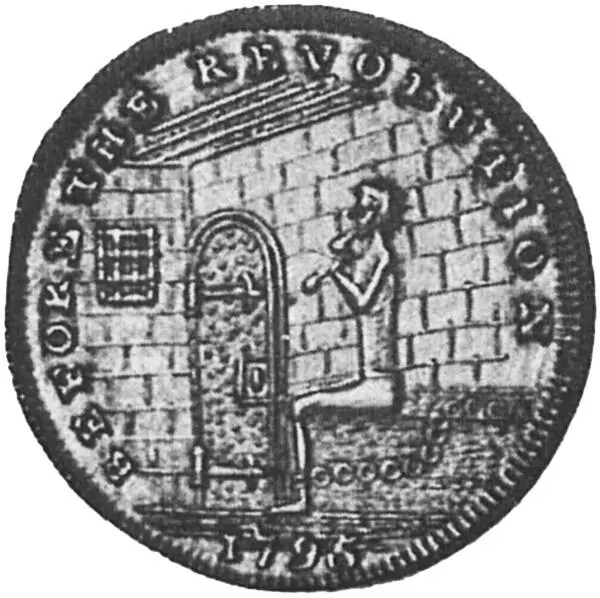

Figuras 1 y 2. «Antes de la revolución» y «Después de la revolución». Dos fichas monetiformes acuñadas por Thomas Spence.

A

LA BÚSQUEDA

1. La tumba de una mujer

Un ventoso día otoñal del año 2000 fui a dar un paseo con mi familia y unos amigos por el camino de sirga del Gran Canal, a las afueras de Dublín. Nos estábamos tomando un fin de semana de descanso en el trabajo de documentación de archivo sobre la Rebelión irlandesa de 1798. El 98 fue el momento crucial de esa época revolucionaria. La idea era combinar una excursión agradable con un reconocimiento preliminar. En el camino me paré ante un rosal silvestre. Tenía una sola rosa roja, con los pétalos relucientes en la luz del atardecer por las gotas de un chaparrón reciente. Además de formar parte de una época revolucionaria, el 98 se produjo durante el Romanticismo, y esa rosa, en ese lugar, en ese momento, me pareció una señal de ánimo.

Читать дальше