Rachel A. Powsner - Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rachel A. Powsner - Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In a manner analogous to that for excess neutrons, an unstable nucleus with too many protons can undergo a decay that has the effect of converting a proton into a neutron. There are two ways this can occur: positron decay and electron capture. In general, these proton rich nuclei decay by a combination of these two processes.

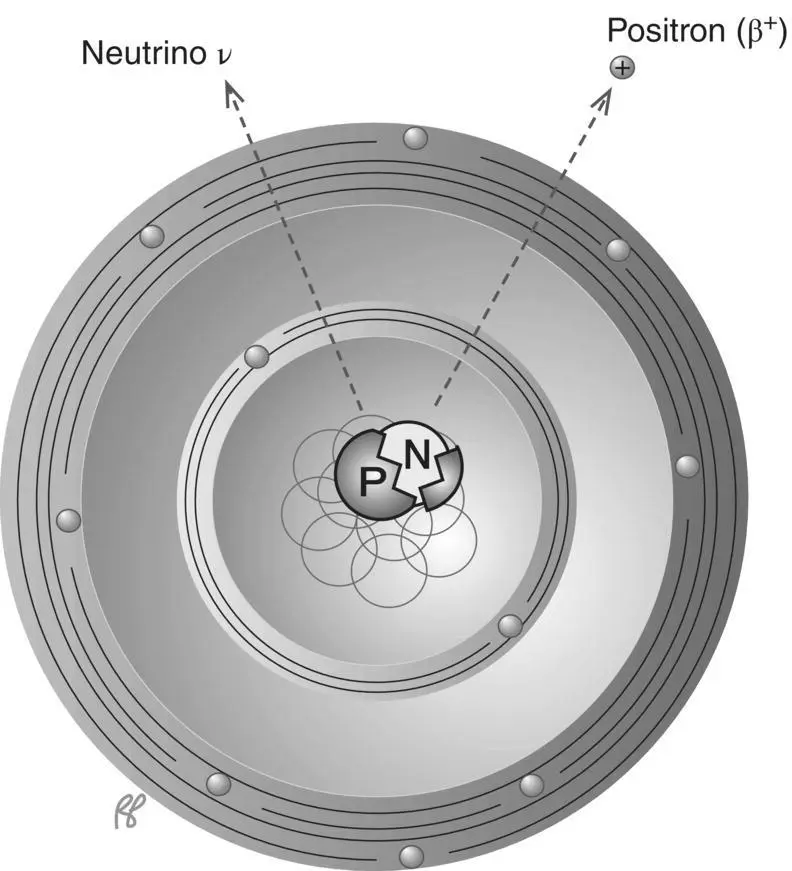

Positron decay:

A proton can be converted into a neutron and a positron, which is an electron with a positive, instead of negative, charge ( Figure 1.16). The positron is also referred to as a positive beta particle or positive electron or anti‐electron. In positron decay, a neutrinois also emitted. In many ways, positron decay is the mirror image of beta decay: positive electron instead of negative electron, neutrino instead of antineutrino. Unlike the negative electron, the positron itself survives only briefly. It quickly encounters an electron (electrons are plentiful in matter), and both are annihilated(see Chapter 8, Figure 8.1). This is why it is considered an anti‐electron. Generally speaking, antiparticles react with the corresponding particle to annihilate both. During the annihilation reaction, the combined mass of the positron and electron is converted into two photons of energy equivalent to the mass destroyed, each with an energy of 511 keV or a total of 1.022 MeV. Following ejection of a positron from a nucleus the atom must also shed an orbital electron to keep the overall charge of the atom neutral. So, in essence, the atom is losing the mass equivalent of two electrons (remember positrons are basically positively charged electrons). Positron emission will only occur when the difference in mass between the parent (original) and daughter atoms is at minimum the mass of two electrons, which, as we will see in Chapter 2, Figure 2.12is equal to 1.02 MeV of energy.

Figure 1.16 β +(positron) decay.

Energy of beta particles and positrons

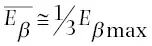

Although the total energy emitted from an atom during beta decay or positron emission is constant, the relative distribution of this energy between the beta particle and antineutrino (or positron and neutrino) is variable. For example, the total amount of available energy released during beta decay of a phosphorus‐32 atom is 1.7 MeV. This energy can be distributed as 0.5 MeV to the beta particle and 1.2 MeV to the antineutrino, or 1.5 MeV to the beta particle and 0.2 MeV to the antineutrino, or 1.7 MeV to the beta particle and no energy to the antineutrino, and so on. In any group of atoms the likelihood of occurrence of each of such combinations is not equal. It is very uncommon, for example, that all of the energy is carried off by the beta particle. It is much more common for the particle to receive less than half of the total amount of energy emitted. This is illustrated by Figure 1.17, a plot of the number of beta particles emitted at each energy from zero to the maximum energy released in the decay. E βmaxis the maximum possible energy that a beta particles can receive during beta decay of any atom,  is the average energy of all beta particles for decay of a group of such atoms. The average energy is approximately one‐third of the maximum energy or

is the average energy of all beta particles for decay of a group of such atoms. The average energy is approximately one‐third of the maximum energy or

Figure 1.17 Beta emissions (both β –and β +) are ejected from the nucleus with energies between 0 and their maximum possible energy ( E βmax). The average energy (  ) is equal to approximately one third of the maximum energy.

) is equal to approximately one third of the maximum energy.

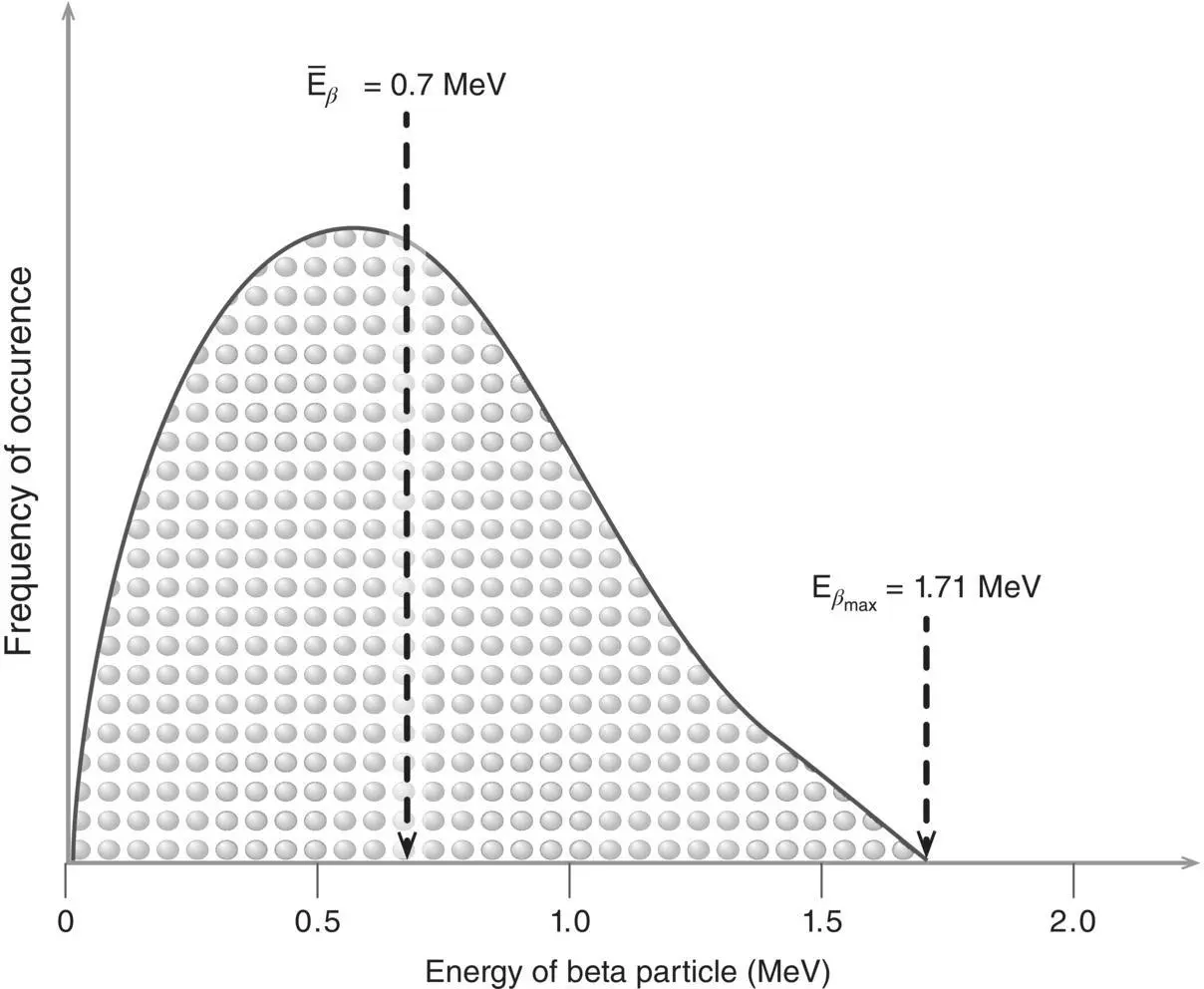

Electron capture:

Through a process that competes with positron decay, a nucleus can combine with one of its inner orbital electrons to achieve the net effect of converting one of the protons in the nucleus into a neutron ( Figure 1.18). An outer‐shell electron then fills the vacancy in the inner shell left by the captured electron. The energy lost by the “fall” of the outer‐shell electron to the inner shell isemitted as an X‐ray.

Figure 1.18 Electron capture.

Appropriate numbers of nucleons, but too much energy

Isomeric transition:

Following alpha and beta decay and electron capture, the nucleus has a more favorable physical configuration of nucleons but usually contains an excess of energy. The nucleus is said to be in an excited state when the energy of the nucleus is greater than its resting level. This excess energy is shed by isomeric transition. This may occur by either or both of two competing reactions: gamma emission or internal conversion. Most isomeric transitions occur as a combination of these two reactions.

Gamma emission:

In this process, excess nuclear energy is emitted as a gamma ray ( Figure 1.19). The name gamma was given to this radiation, before its physical nature was understood, because it was the third (alpha, beta, gamma) type of radiation discovered. A gamma ray is a photon (energy) emitted by an excited nucleus. Despite its unique name, it cannot be distinguished from photons of the same energy from different sources, for example X‐rays.

Internal conversion:

The excited nucleus can transfer its excess energy to an orbital electron (generally an inner‐shell electron) causing the electron to be ejected from the atom. This can only occur if the excess energy is greater than the binding energy of the electron. This electron is called a conversion electron. The resulting inner orbital vacancy is rapidly filled with an outer‐shell electron (as the atom assumes a more stable state, inner orbitals are filled before outer orbitals). The energy released as a result of the “fall” of an outer‐shell electron to an inner shell is emitted as an X‐ray ( Figure 1.20a) or as a free electron, an Auger electron( Figure 1.20b). The emitted X‐ray is called a characteristic X‐raybecause its energy always equals the difference in binding energies between the electron shells.

Decay notation

Decay from an unstable parent nuclide to a more stable daughter nuclide can occur in a series of steps, with the production of particles and photons characteristic of each step. A standard notation is used to describe these steps ( Figure 1.21). The uppermost level of the schematic is the state with the greatest energy. As the nuclide decays by losing energy and/or particles, lower horizontal levels represent states of relatively lower energy. Directional arrows from one level to the next indicate the type of decay. By convention, an oblique line angled downward and to the left indicates electron capture; downward and to the right, beta emission; and a vertical arrow, an isomeric transition. The dogleg is used for positron emission. A dogleg with a “ Z ” denotes alpha decay. Notice that a pathway ending to the left, as in electron capture or positron emission, corresponds to a decrease in atomic number. On the other hand, a line ending to the right, as in beta emission, corresponds to an increase in atomic number.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Physics, Instrumentation, and Radiation Biology» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.