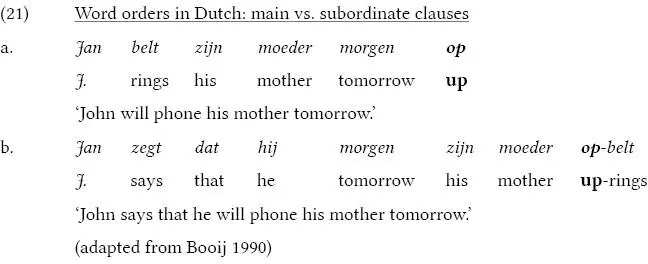

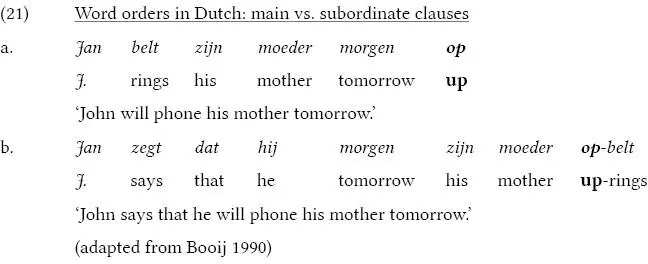

As Booij & Van Kemenade (2003: 6) remark, the separability of separable complex verbs also manifests itself in the position of the infinitival particle te, which occurs between the two elements of separable complex verbs (e.g. op tebellen ‘to call up’), as well as in the form of the perfect passive participle, with the prefix ge- placed in between the preverb and the verbal stem ( op- ge-beld ‘called up’). Separable complex verbs also behave similarly in derivational morphology: for example, the ge- nominalization of opbellen is op- ge-bel ‘phone call’, with the nominalizing prefix occurring between the preverb and the verbal base.

3.1.3. The origin of preverbs

As discussed in Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2, in a number of Indo-European languages, the same set of morphemes can occur in adverbial, preverbal and adpositional (pre- and post-positional) position. From Kuryłowicz (1964: 171) onward, the relation among adverbs, preverbs and adpositions has been interpreted at the diachronic level as follows: “The fact that in the Indo-European languages many an indeclinable may function both as preverb and as preposition has been a sufficient reason for attributing to them an adverbial origin. Such an assumption fully accounts for their subsequent functional bifurcation. On the one hand, a group consisting of adverb + verb may develop into a compound […]. On the other hand, within a construction [(verb + adverb) + oblique case] a syntactic shift may entail a new articulation [verb + (adverb + oblique case)], i.e. (preposition + oblique case)” (italics are Kuryłowicz’s). Before Kuryłowicz, the adverbial origin of Indo-European preverbs was also posited by Brugmann (1890: 758ff.), Meillet (1903: 158ff., 193), Saussure (1922: 246ff.), and Wackernagel (1924: 153ff.). After Kuryłowicz, many scholars embraced his theory, including Chantraine (1953: 82ff.), Baldi (1979), Krisch (1984: Ch. 3) Beekes (1995: 218), Rousseau (1995:12), Hoenigswald (1998: 257), and Fortson (2004: 139).

Thus, in the early stages of Indo-European, preverbs were independent constituents of an adverbial character. Later on, these adverbs started gravitating semantically toward a verb, or toward an inflected NP: adverbs either came to modify the meaning of a verb, or to specify the value of a case. After such adverb+verb or adverb+NP combinations became conventionalized, adverbs began to lose their autonomy, and to be part of proper syntactic constituents with verbs or noun phrases: they underwent grammaticalization. The functional bifurcation of local adverbs into preverbs or adpositions is mirrored by their increasing obligatorification for the structure of the constituents in which they occur.

From the adpositional side, such an obligatorification undergone by previously free-standing adverbs has been interpreted as a piece of evidence demonstrating the rise of configurational syntax among Indo-European languages (cf. Hewson & Bubenik 2006; Luraghi 2009, 2010, forthc.b, forthc.c; Reinöhl 2016, and references therein). The grammaticalization of adpositions can thus be framed within a larger picture, whereby non-configurational languages, exhibiting originally (i) free constituent order, (ii) discontinuous nominal expressions, and (iii) null anaphora (Hale 1983), such as ancient Indo-European languages, undergo a series of changes that bring about features of configurationality. In fact, a number of scholars (Meillet & Vendryes 1924: 520; Hewson & Bubenik 2006) regard the creation of adpositional phrases as crucial in creating configurationality in Indo-European.

As even in the oldest Indo-European languages it is relatively unusual for these morphemes to display the purely adverbial function (cf. e.g. Dunkel 1976, 1980; Luraghi 2001), preverb+verb and adposition+NP combinations have been reconstructed Proto-Indo-European itself. Specifically, in his pioneering works on Old Indo-Aryan and Proto-Indo-European word order, Delbrück (1878: 13, 1888: 15–16) formulated the following rule: preverb/adposition usually precedes its verb, but follows its case (cf. further McCone 2006: 41ff.). However, Delbrück’s observation on word order, whether correct or not (cf. fn. 15 in this Chapter, and Chapter 4 on Vedic), does not imply that either bound preverbs (i.e. prefixes) proper or adpositions proper (i.e. obligatory adpositions selecting the case that accompanies them) can be assumed for Proto-Indo-European (on the development of configurational syntax and the internal structure of Indo-European PPs, see Hewson & Bubenik 2006; Luraghi 2009, 2010, forthc.b, forthc.c; Reinöhl 2016, and references therein). Rather, in the oldest branches of Indo-European, the relationship that holds between preverbs+verbs and adpositions+NPs can be described primarily as modification, rather than as specification or government (cf. further Boley 2004: 34; Chapters 4 and 5). In her work on tmesis in Hittite, Vedic and Homeric Greek, Boley (2004: 52) summarizes this view as follows: “the preverb/preposition [“place word” in her terminology] is clearly an addition to what we regard as a basic sentence.” By contrast, in most Indo-European languages less ancient than Vedic and Homeric Greek, including Old Church Slavic and Old Irish (Chapters 6 and 7), adpositions seem to already function as heads of the phrases in which they occur: their omission brings about agrammaticality and/or alterations in meaning.

3.1.4. Preverbs as a terminological and a typological problem

3.1.4.1. The terminological side of the issue

As discussed in Sections 3.1.2 and 3.1.3, the same Proto-Indo-European morphemes that developed into preverbs also developed into adpositions in later languages. Additionally, these morphemes originally functioned as free constituents of an adverbial character, thus being able to modify whole sentences, nouns and verbs. Furthermore, preverbs encompass a wide range of meanings and functions, different from their basic contribution of adding spatial specifications to verbal stems (cf. Section 3.1.1). This multiplicity of functions is mirrored in a high variability in the terminology referring to these morphemes, as I discuss in what follows.

Precisely because of such widely varying placements, meanings, and functions, Cuzzolin et al. (2006) consider these morphemes to constitute a problematic morphological category. Accordingly, the authors call the morphemes that belong to this category “adverbs-adpositions-preverbs” (ADVs-ADPs-PREVs). Equally descriptive labels are employed by Bolinger (1971) and Friedrich (1987): the former, in his work on English, uses the abbreviation “adprep” to combine their adverbial and prepositional function; the latter employs the same label to refer to these morphemes across the whole Indo-European language family.

Friedrich (1987), in the heading of the same paper, explains what he means by “adprep”: in the subheading, within brackets, he adds the term “spatio-temporal auxiliaries”. The “spatio-temporal” part specifies the original semantics of these elements, whereas the “auxiliaries” part indicates that that they are usually added as adverbial modifiers to a predicate or a noun. The primary spatial value of Hittite, Vedic, and Homeric ADVs-ADPs-PREVs also supports Boley’s (2004) choice, who calls these elements “place words”, as mentioned above .

The fact that ADVs-ADPs-PREVs originally functioned as modifiers, and not as syntactic heads, is also emphasized in Ivanov (1973) and in Friedrich (1976), who opt for “locative auxiliaries”. The label “satellites” also points out the fact that these elements functionally gravitate toward a verbal center as its modifiers. The term “satellite” is used in the literature on the typology of motion events as well (from Talmy 1983 onward), and occasionally in works on the Old Irish verbal complex (e.g. McCone 2006: vii titles a section of his monography “The Verb and its Satellites in Proto-Indo-European”). Patri (2007) also focuses on the modifier character of preverbs, by calling them determinant adverbial(s) ‘adverbial determiner(s)’.

Читать дальше