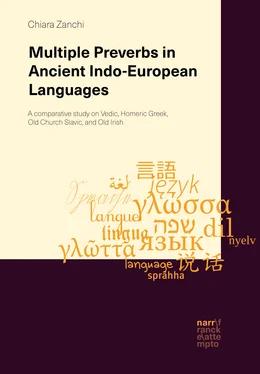

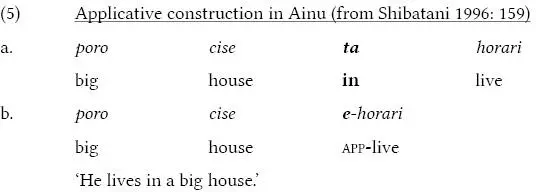

Since the publishing of the work of Hopper & Thompson (1980), it has been acknowledged that a linkage exists between telicity-perfectivity and transitivity: in particular, a high degree of telicity-perfectivity is implied by prototypical transitivity (cf. Section 2.3.2.2). Therefore, as preverbs can mark telicity and perfectivity, they are also candidates to function as so-called “applicative” markers. Applicatives are overt verbal morphemes that “allow the coding of a thematically peripheral argument or adjunct as a core-object argument” (Peterson 2007: 1). In (5), an example from Ainu (isolated, Hokkaido, Japan) is shown:

The same state of affairs is denoted in (5)a-b: in the former example, Location is expressed through a postpositional phrase introduced by ta ‘in’; in the latter sentence,, Location is promoted to direct object of the composite verb e-horari , which contains the crucial applicative prefix e-.

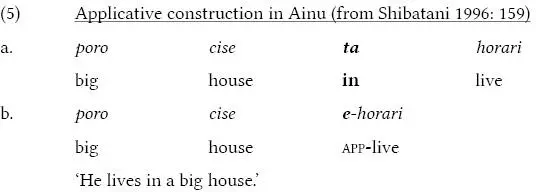

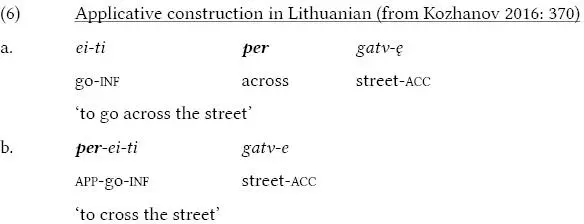

A typological parallel has been drawn between Indo-European preverbs and applicatives, as Indo-European preverbs also seem able to promote an adjunct to argumental status (on Vedic, cf. Chapter 4; Danesi 2009; and reference therein; on Ancient Greek, cf. Chapter 5; Horrocks 1981; Viti 2008a; on Lithuanian, cf. Kozhanov 2016). In (6), it is shown that Lithuanian preverbs can function in the same way as the applicatives in (5): the simplex verb eiti ‘go’ is intransitive, and takes an optional PP per+ ACC expressing Path in (6)a. By contrast, the same morpheme per occurs in front of eiti as a preverb in (6)b: accordingly, the Path-participant is promoted to direct object.

The preverb/applicative per- of Lithuanian is etymologically connected with the corresponding preposition per : they both go back to the same Proto-Indo-European adverb * pér (LIPP II 607). The linkage just outlined between Lithuanian preverbs/applicatives and prepositions is common within the Indo-European languages, in which preverbs can usually also function as adpositions (that is, pre- and postpositions) and adverbs (cf. Sections 3.1.2 and 3.1.3). This linkage also displays typological parallels: the same morphemes that function as applicatives can also occur out of the preverbal context, as adpositions or adverbs, in non-Indo-European languages, including for example Ayoreo (Zamucoan, Paraguay, Bolivia; Ciucci 2014 with references). Switching to the diachronic plane, it is worth mentioning that adpositions constitute one of the possible sources for applicatives (cf. Seiter 1979 on Oceanic languages; Weir 1986 on Nadëb, Nadahup, Amazonas, Brazil; Craig & Hale 1988 on Algoquian languages; Peterson 2007: 125ff.). This development is accounted for as a discourse-oriented grammaticalization: according to Craig & Hale (1988), what has triggered the reanalysis of an adposition as a preverb (i.e. applicative) is the null anaphora of the noun phrase taken by the preposition. Though a grammaticalization path triggered by null anaphora is difficult to hypothesize for Indo-European preverbs, due to the presence of a developed case system complicating the whole picture, a number of scholars also believe that pragmatic features, such as topicality, are essential to account for certain developments of Indo-European preverbs (cf. Sections 3.1.2 below and 3.1.3; Viti 2008a, 2008b).

The assessment of the actual role played by Indo-European preverbs in promoting an adjunct to argumental status is complicated by the fact that Proto-Indo-European and many daughter languages possess the previously mentioned case systems. On the one hand, it is true that preverbs can centralize an adjunct, thus aligning themselves with applicatives. On the other hand, the centralized adjunct frequently does not exhibit all the coding and behavioral properties of direct objects proper: often, it does not receive the usual coding and does not play the usual role for direct objects, i.e. an accusative case expressing the Patient (e.g. Viti 2008a); in addition, these putative direct objects cannot always be passivized (e.g. Kulikov 2012).

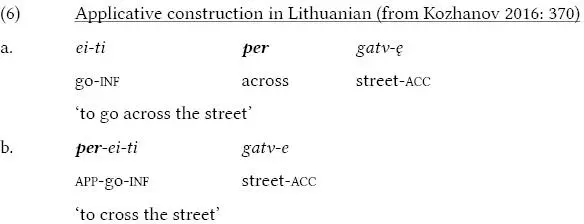

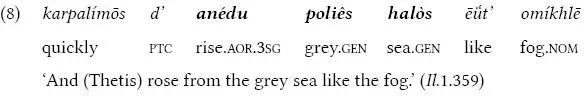

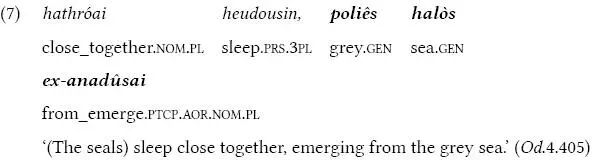

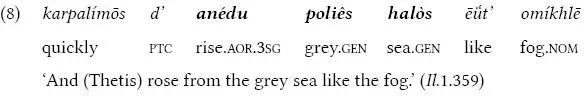

Moreover, in Proto-Indo-European and in a number of ancient Indo-European languages, cases not only serve the grammar (i.e. by distinguishing subjects from objects), but also retain parts of their concrete meanings (cf. especially Kuryłowicz 1964: 179ff. on the distinction between grammatical and concrete cases). Accordingly, in many contexts, preverbs are not strictly necessary to allow for an adpositionless second argument, though they certainly contribute to clarifying the meaning of verbs and adpositionless cases. For example, in Ancient Greek, the usage of the adpositionless genitive poliês halòs ‘gray sea’ is allowed both with a composite containing ex- ‘out of’ ( ex-ana-dúomai ‘emerge from’) and with a composite lacking it ( ana-dúomai ‘emerge’):

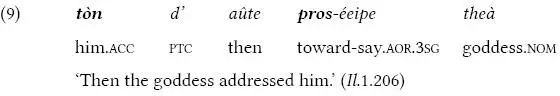

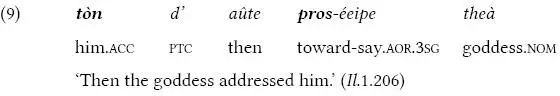

In addition, the extension of the transitive construction seems not always to be triggered by the occurrence of preverbs, but rather by the own frequency of this construction. This is true, for example, for Ancient Greek (cf. Luraghi 2010). Horrocks (1981: 41), alleging the applicative usage of Ancient Greek preverbs, mentions the composite pros-eîpon, which can take an accusative argument ( tòn ‘him’ expressing the Addressee) in the sense of ‘address someone’, as in (9):

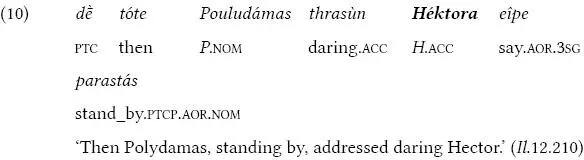

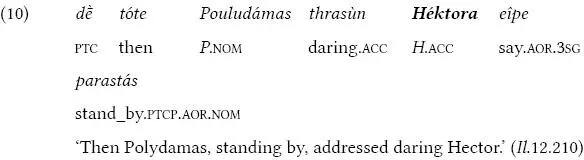

Horrocks remarks that the simplex eîpon cannot take a different direct object from the cognate épos ‘word’ (or its non-cognate synonym, mûthon ) or the indefinite pronoun ti ‘something’. However, the example in (10) contests this claim: the simplex verb eîpon takes the accusative of the Addressee, that is, Héktora .

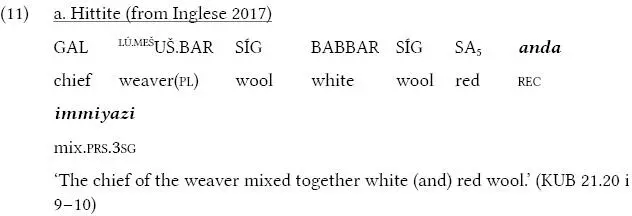

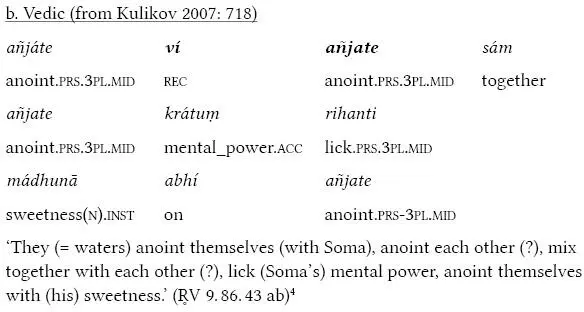

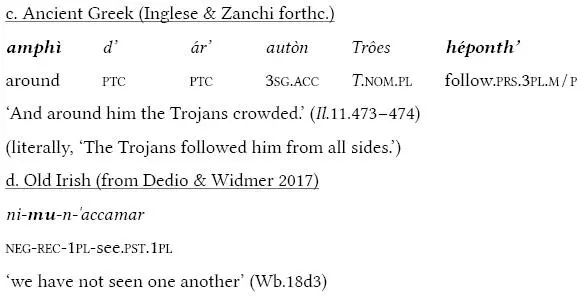

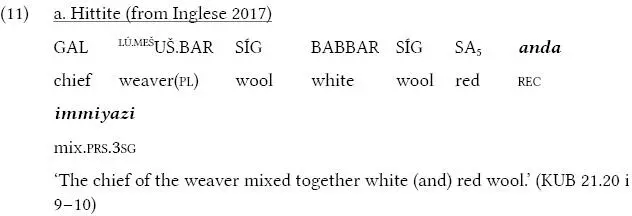

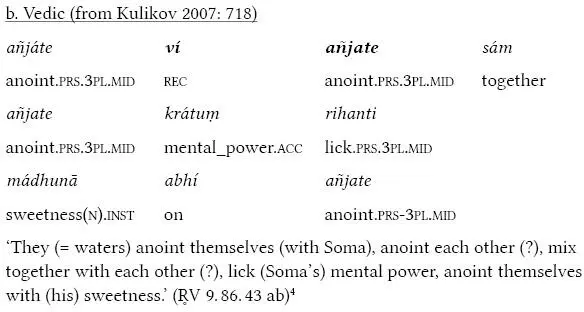

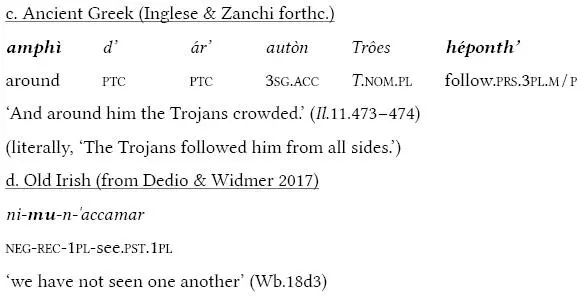

In fact, it is undeniable that preverbs are connected with valency-related formations, as they are involved in making up reciprocal constructions in different ancient Indo-European languages, as shown in (11)a-c:

Читать дальше