In (11)a from Hittite, the verb imiya- ‘mix’ and the preverb anda ‘in’ indicate an object-oriented spatial reciprocal situation. In (11)b from Vedic, a canonical intransitive reciprocal is expressed by means of the preverb ví ‘in two spaces, in two times, in different directions’. In the Homeric passage in (11)c, the reciprocal meaning emerges from the preverb-verb construction with amphí ‘around’, detached from the plural verb héponth’(i) ‘follow’. In the Old Irish passage in (11)d, a personal reciprocal construction is formed with the verb taking the plural verbal endings, and preceded by the preverb imm- , which in this context surfaces as -mu- .5

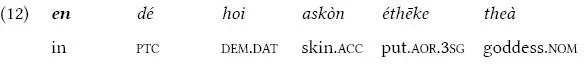

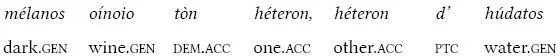

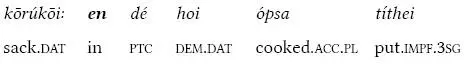

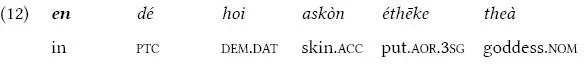

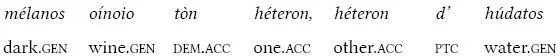

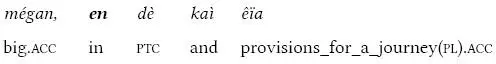

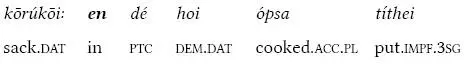

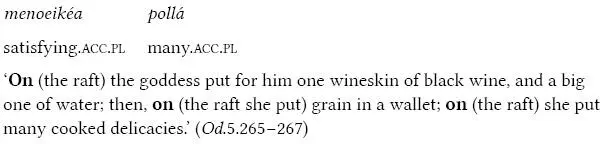

Together with the semantic and syntactic functions outlined above, preverbs can also serve discourse-related purposes. Specifically, Boley (2004: 56–58) describes Hittite, Vedic, and Homeric preverbs (i.e. place words in her terms; cf. Section 3.1.4.1) as elements able to draw anaphoric reference, and thus to contribute to textual cohesion. The following example from the Odyssey is instructive in this respect:

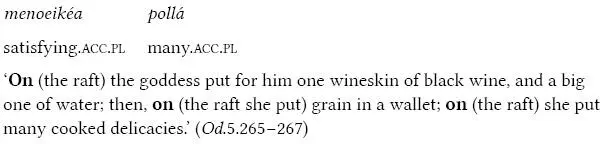

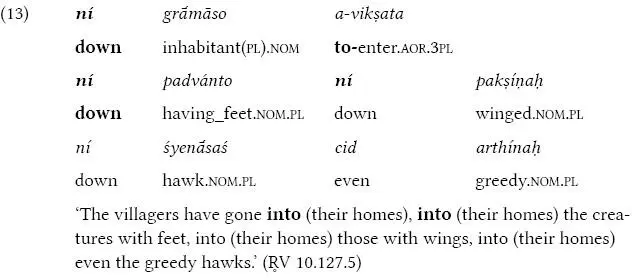

In (12), no overt referent occurs accompanying the preverb en in clause-initial position (cf. Section 3.1.2), though one understands from the preceding context that the preverb en refers to a previously mentioned raft. Boley’s remark is supported by the quantitative analysis carried out by Viti (2008a) on Homeric poems: Viti showed that the majority of referents linked to preverbs are topical, and thus either previously mentioned in the discourse context, or known within speakers’ encyclopedic knowledge. The cohesive function of preverb repetition in Vedic and Homeric Greek has been investigated by Dunkel (1976, 1979), and Klein (e.g. 1987, 2007, 2008). A relevant Vedic example follows: in (13), the preverb ní ‘down’ is repeated three times in the stanza, specifically at the beginning of each verse.

3.1.2. The positional properties of preverbs

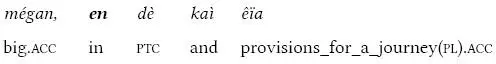

In Indo-European, the same morpheme that functions as a preverb can also occur outside the preverbal context as an adverb or as an adposition. Garde (2004: 104–105) lists a number of such morphemes from five Indo-European languages: Ancient Greek, Latin, German, Russian, and Lithuanian. To Garde’s language sample, I add Vedic, Old Church Slavic, and Old Irish, which are relevant for this work (see Whitney 1955[1879]: 396ff.; and Renou 1952: 316ff. for Vedic; Aitzetmüller: 1991: 154ff.; and Lunt 1965: 82, 151 on Old Church Slavic; VKG II 242ff.; and GOI 495ff. on Old Irish). Following Garde, I mark the morphemes that can only function as prepositions differently from those that only occur in preverbal position: the former are assigned the label Prep, the latter Prev. Morphemes carrying both labels, Prep-Prev, also feature both functions.1

1 Preverb catalogue in a number of Indo-European languagesVedic (cf. Chapter 4)Prep-Prev – 17: áchā, áti, ádhi, ánu, ántar, ápa, ápi, abhí, áva, úpa, tirás, nís, pári, purás, prá, práti, sám Prep – 3: upári, parás, púrā Prev – 4: úd, ní, párā, ví Ancient Greek (cf. Chapter 5)Prep-Prev – 19: amphí, aná, antí, apó, diá, eis, ek, en, epí, katá, metá, pará, perí, pró, prós, sún, hupó, hupér Old Church Slavic (cf. Chapter 6)Prep-Prev – 16: bedъ, do, iz(ъ), na, nadъ, o(b), ot(ъ), po, podъ, prědъ, pri, sъ, vъ(n), vъz(ъ), u, zа Prep – 1: kъ Prev – 4: prě-, prо-, raz-, vy- Old Irish (cf. Chapter 7)Prep-Prev – 15: air, com, dí, ess, eter, fo, for, frith, íar, imb, in, re, sech, tar, tri Prep – 1: ó Prev – 6: ad-, aith-, ne-, uss-, ro-, to- LatinPrep-Prev – 14: ab, ad, ante, cum/con-, de, ex, in, ob, per, prae, pro, sub, super, trans Prep – 1: post Prev – 2: dis-, red- GermanPrep-Prev – 15: ab, an, auf, bei, durch, in/ein-, mit, nach, über, um, unter, vor, wider, zu Prep – 5: für, gegen, ohne, seit, von Prev – 5: be-, ge-, ver-, zer- RussianPrep-Prev – 15: v, do, za, iz, na, nad, o/ob, ot, pered/pred-, po, pod, pri, pro, s, u Prep – 3: bez, k, čerez Prev – 4: vz-, vy-, pere-, raz- LithuanianPrep-Prev – 10: ant-, apie/ap-, į, iš, nuo, po/pa-, per, prie, su, už Prep – 4: arti, be, iki, tils PrevP – 1: at-

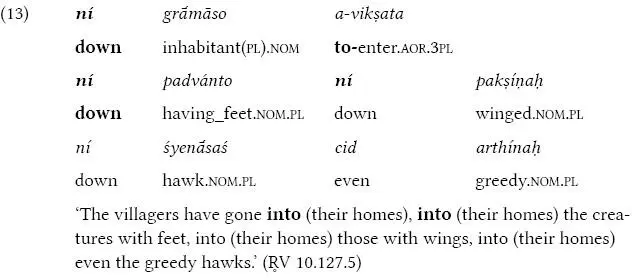

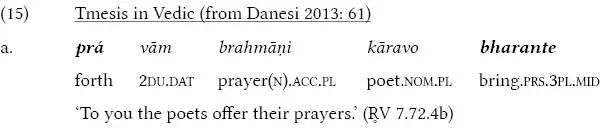

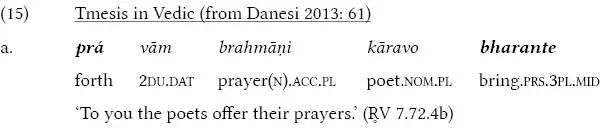

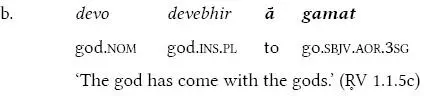

In a number of ancient Indo-European languages – notably in Hittite, Vedic, Old Avestan, Homeric Greek, Early Latin, Archaic Old Irish, and Gothic – preverbs can be separated from the verb that they modify, despite retaining their semantic cohesion with it. This apparent split is usually called “tmesis” (< AG témnō ‘cut’), and is exemplified in (15):

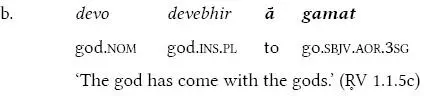

In (15)a, the preverb prá modifies the meaning of the root √bhr̥- ‘carry, bring’, resulting in ‘offer’. The two elements of the composite are separated from one another: prá is sentence-initial, whereas the main verb bharante is sentence-final. In (15)b, instead, the preverb ā́, which reverses the deictic orientation of √gam- ‘go to, approach’, shows up immediately in front of the verb gamat, but remains a constituent independent of it, as is proved by the accentuation. As demonstrated by Watkins (1963, 1964), in some ancient Indo-European languages, tmesis is not a literary artifact, but rather a testimony of the fuzzy categorial status of a class of morphemes which can function as free adverbs, adpositions or preverbs (on tmesis, cf. further De Angelis 2004 and references therein).2 Hence, “tmesis” (literally) ‘cutting apart’ is a misleading label assigned by ancient grammarians to the apparent split exemplified in (15)a.

The papers by Watkins (1963, 1964) describe the following types of verbal tmesis:3

1 #PN(E) …V(…)# (cf. (15)a).4 This type of tmesis has already been described by Wackernagel (1924: 171f.; translation mine): “From ancient times, tmesis mostly occurs if the preverb shows up at the beginning of the sentence.”5 In addition to Vedic, Hittite, Homeric Greek, Archaic Latin, and Archaic Old Irish allow this pattern (Watkins 1964).

Читать дальше