3. Preverbs: an overview

3.1. Preverbs in Indo-European

3.1.1. Preverbs: definition and functions

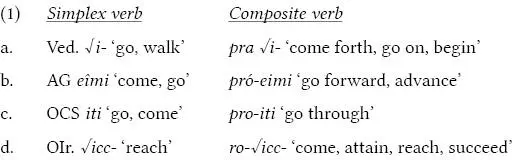

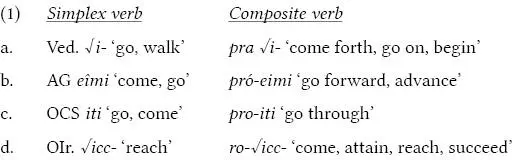

Preverbs are synchronically uninflected morphemes that occur in front of a verbal stem and modify its meaning, as shown in (1).1

Examples (1)a-d contain the reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European local adverb *pr-ó ‘forward, forth’ (LIPP II 636–637) occurring in front of a motion verb and modifying its meaning accordingly.2 Vedic, Ancient Greek, and Old Church Slavic motion verbs of (1)a-d go back to the same PIE root, i.e. *h 1ei̯- ‘go, walk’ (IEW 293–296; LIV 2232), whereas the Old Irish one is related to PIE *h 2nek̂- ‘reach’ (IEW 316–318; LIV 2282).

Though the notion of preverb was coined and is traditionally employed in the field of Indo-European studies (Booij & Van Kemenade 2003: 1; the term “preverb” itself is a calque from the post-Classical Latin lemma prae-verbium , attested in Varro, De lingua latina 6.38, and in Gellius 6.7.5), many non-Indo-European languages also exhibit an array of uninflected morphemes that have the same functions as Indo-European preverbs (cf. Section 3.3). The functions of Indo-European preverbs are described in what follows (cf. Bader 1997; Booij & Van Kemenade 2003).

In the first place, preverbs operate at the semantic level: they modify the meaning of the verb onto which they attach in different ways. Primarily, they provide a verbal root with spatial information: preverbs can give indication to location events, or specify the direction of motion. For example, the Ancient Greek and Old Irish simplex caused motion verbs phérō ‘bring, carry’ and beirid ‘carry, bring’ (< PIE * b her- ‘carry, bring’; cf. IEW 128ff.; LIV 276ff.) can be combined with a number of preverbs, resulting in the different composites displayed in (2) and (3) (this list of composites is illustrative but not exhaustive for either language; the added preverb and its semantic contributions are highlighted in bold):

1 AG composites with phérō ‘bring, carry’ ana - phérō ‘bring up, bring back, report’ apo - phérō ‘bring away, bring back, hand in’ dia - phérō ‘carry in different ways, differ’ ek - phérō ‘carry out of’ em - phérō ‘carry in’ eis - phérō ‘carry in(to), contribute, introduce’ epi - phérō ‘bring upon’ kata - phérō ‘bring down’ meta - phérō ‘carry across, translate’ pro - phérō ‘bring forward, utter’ pros - phérō ‘bring to, offer, pay’ huper - phérō ‘carry over, be preeminent’

2 OIr. composites with beirid ‘bring, carry’ ar · beir (literally) ‘before bring’ → ‘live, eat, use’ as · beir (literally) ‘out_of bring’ → ‘say, speak’ con · beir ‘bring together, conceive’ do · beir ‘bring to, give’ fo · beir ‘bring under, subdue’ for · beir (literally) ‘bring over’ → ‘grow, surpass’ fris · beir (literally) ‘bring against’ → ‘oppose, resist, obstruct’ imm · beir ‘carry around, put, employ’

Preverb-verb combinations can result in non-compositional (idiomatic or unpredictable) meanings: put another way, the meaning of the resulting composite verbs cannot always be inferred from the sum of the meanings of their elements. Among composites in (2) and (3), the following show non-compositional semantics: AG ana-phérō ‘report’, apo-phérō ‘hand in’, dia-phérō ‘differ’, meta-phérō ‘translate’ , pro-phérō ‘utter’, and huper-phérō ‘be preeminent’; OIr. ar·beir ‘live, eat, use’, as·beir ‘say, speak’, con·beir ‘conceive’, for·beir ‘grow, surpass’, imm·beir ‘employ’. Several similar non-compositional developments occur across different languages: for example, in both Ancient Greek and Old Irish, the root for ‘bring’, combined with different preverbs (AG pro- ‘forth, forward’, OIr. ess- ‘out of’), produces a communication verb ( pro-phérō ‘utter’(2)j; as·beir ‘say, speak’ (3)b; cf. also Rus. pro-iz-nosit’ ‘ forth-out_of-bring’ → ‘say, pronounce, utter’ that contains the Slavic equivalents for both preverbs, and a verbal base for bringing). Arguably, these similarities are byproducts of the lexicalization of the Container metaphor, according to which human body is conceptualized as a container (cf. Chapter 2). In a number of formations, preverbs develop lexical meanings beyond the etymological spatial ones: for example, the preverb apo- ‘away from’ basically expresses ablativity, but it comes to mean ‘back’ in apo-phérō ‘bring back’. The same preverb also gains more abstract meanings. For example, in combination with the communication verb eîpon ‘say’, apo- expresses refusal, such as in ap-eîpon ‘deny’ (< apo- ‘ away’ + eîpon ‘say’).

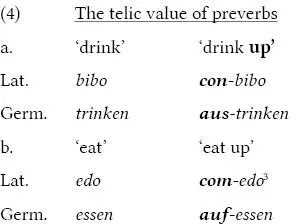

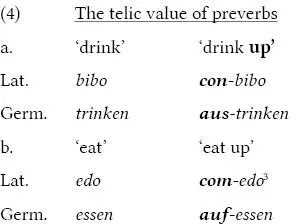

Importantly, preverbs can also carry out more grammatical functions than those outlined above. To begin with, preverbs frequently modify the actionality or lexical aspect of the verb onto which they attach, from durative to punctual or from atelic to telic. This function has been ascribed to preverbs of Indo-European languages, including Vedic, Homeric Greek, Old Church Slavic, and Old Irish (cf. the relative discussions in Chapters 4–7). Relevant examples also come from other Indo-European languages, both ancient and modern, as is shown in (4).

In addition, preverbs can bring about other types of actional meanings such as iterative (e.g. AG ana-metrḗsthai ‘start again’), distributive (OR po-jati ‘take for multiple times’), delimitative (OR po-sěděti ‘sit for a while’), and ingressive (e.g. Ved. prá√an ‘ startbreathing’, ní√svap- ‘ fallasleep’; AG hupo-perkázō ‘ begin inch by inchto assume a dark color’; OCS vъs-po-męnǫti ‘ startremembering’; OR raz-bolětisja ‘ fallill’).

In Slavic languages, it is noteworthy that preverbs not only modify the lexical aspect of verbs, but have developed into fully-fledged markers of grammatical aspect: preverbs underwent grammaticalization into “bounder perfectives” (Bybee 1985; Dahl 1985; Bybee & Dahl 1989; Bybee, Perkins & Pagliuca 1994; cf. the thorough collection of references contained in Ruvoletto 2016: 8–33). Such a typologically unusual development and its motivations are discussed in Chapter 6: even in the most anciently attested variety of Slavic, Old Church Slavic, one can find evidence for the subsequent expansion of the so-called “Slavic-style aspect” (cf. also Eckhoff & Haug 2015; Wiemer & Seržant 2017). As is shown in Chapter 7, Old Irish preverbs also carry out grammatical functions: specifically, the preverb ro (< PIE *pr-ó ‘forward, forth’) is paradigmaticized to express perfectivity; the contentless preverb no (< PIE * nú ‘now’; LIPP II 577) behaves as a verbal auxiliary under certain morphosyntactic conditions.

Читать дальше