The logistics are as follows:

An accessory archwire, custom‐designed eruption spring or elastic chain is ligated in active mode between a convenient location on the main arch and the attachment on the impacted tooth, the aim being to erupt the tooth.

In order to overcome the tendency of the reactive force to intrude the teeth on that side of the dental arch of that jaw, vertical elastics are prescribed to be placed by the patient between convenient and easily accessible hooks or buttons between upper and lower appliances.

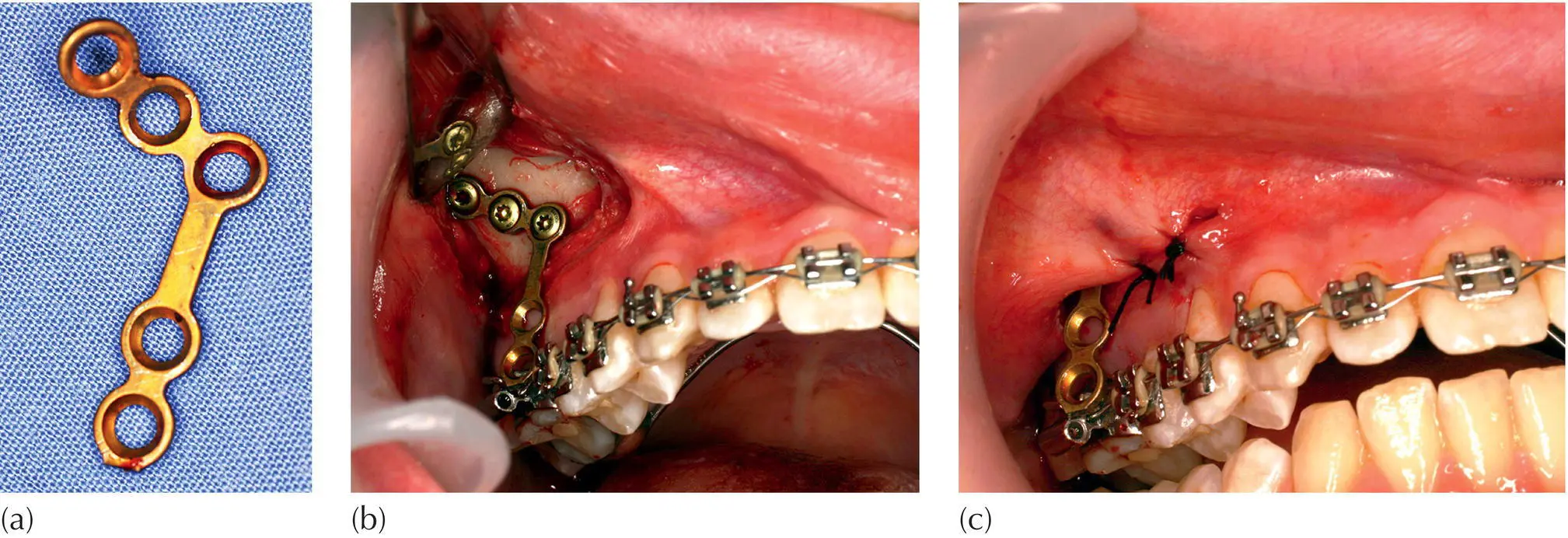

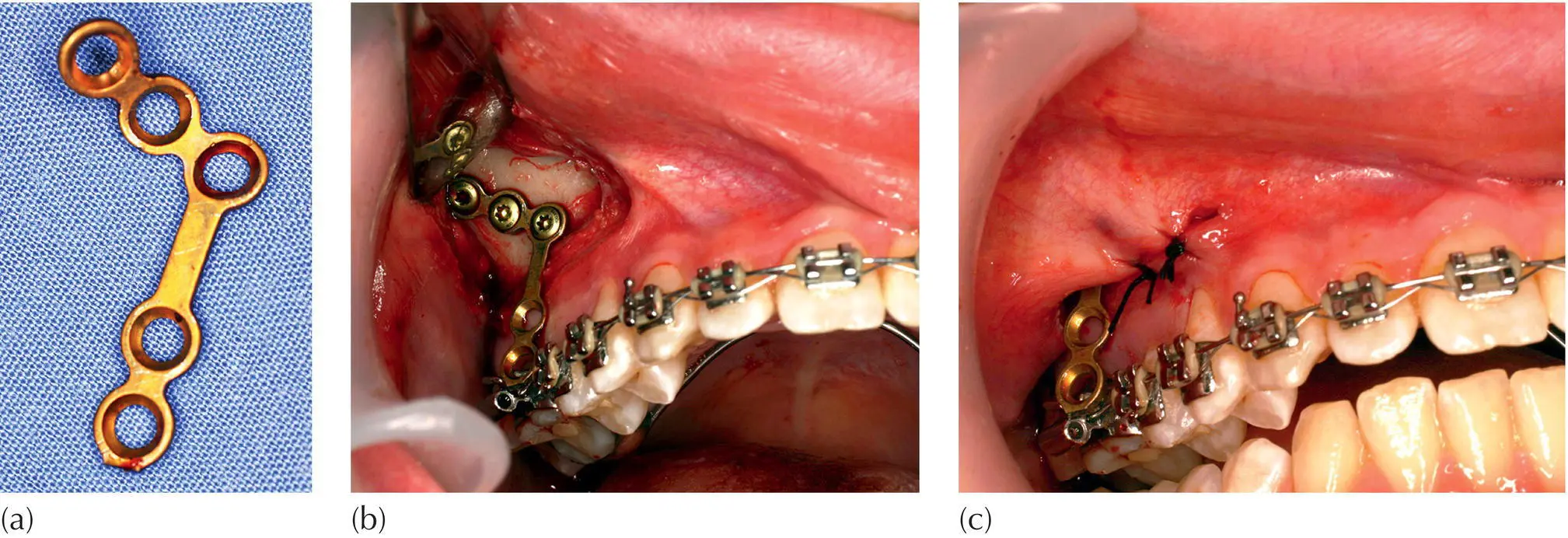

An indirect anchorage system is thus created in which active extrusive forces are applied and controlled by the orthodontist. Loss of anchorage in the same jaw (intrusion of the teeth) is combatted by the patient placing intermaxillary vertical elastics. Loss of anchorage in the opposite jaw (extrusion of the teeth) is prevented by ligation to a TAD in that jaw ( Figure 2.8a–c).

When a maxillary impacted canine does not respond to extrusive forces that are applied from a molar‐to‐molar, fully bracketed orthodontic set‐up, it may be due to ankylosis or to invasive cervical root resorption (ICRR). As the result, a distinct cant of the occlusal plane is produced, due to intrusion of all the teeth ligated to the archwire, but mostly of the immediately adjacent teeth ( Figure 2.8), illustrating severe loss of anchorage. If the orthodontist then looks to include the mandibular dental arch to increase the anchorage, while maintaining the extrusive force on the canine, there will be no improvement, but the teeth in the lower jaw will begin to over‐erupt and a cant will develop in that jaw.

Once the diagnosis has been made, the canine needs to be disconnected from the extrusive element and the cant must be corrected. In order to achieve this, a TAD screw should be placed in the lower jaw and linked by an elastic chain to the full lower archwire. This indirect anchorage system guarantees the anchorage potential of the mandibular dentition. The over‐eruption and asymmetry may be corrected by vertical intrusion in the mandible and, with intermaxillary up‐and‐down elastics, vertical extrusion in the maxilla, to restore the occlusal plane and the occlusion to normal. Only if the ICRR or ankylosis of the canine can be treated successfully can vertical forces then be reapplied, with the expectation of a positive outcome.

The phenomenon of non‐eruption of a tooth in one jaw is often accompanied by over‐eruption of its antagonist, particularly in the molar region. The ostensibly successful resolution of an impacted mandibular second molar may actually be prejudiced by being prevented from reaching the occlusal plane, due to its elongated opposite number. To treat the over‐erupted tooth, a simple titanium screw implant may be inserted on the palatal side of the alveolus adjacent to the second molar and an elastic chain stretched from this TAD to the zygomatic plate, across the occlusal surface of the tooth. In this manner, intrusive force is applied by the chain and a rapid reduction in the height of the tooth may be achieved. This reduction in height will then permit the vertical elastic from the plate to the mandibular second molar to erupt the tooth to its ideal height in relation to the occlusal plane, without the need to involve conventional multibracketed orthodontics in the eruption process.

It has been shown that titanium screws have a success rate in excess of 80% [20], although this author is unable to reach that level of success. Notwithstanding the fact that the screws are easily and rapidly replaced in the event of failure, the very failure itself creates a nuisance in the smooth running of the treatment. Accordingly, in cases where considerable movement is needed on a fairly long‐term basis, a good alternative is the use of a malleable titanium plate onlay. This may be adapted to the shape of an area of bone surface, such as in the palate or the inferior surface of the zygomatic process of the maxilla [21]. Titanium screws are then used to secure the plate to the strategically selected area, and the flap sutured to leave only the extremity of the plate exposed at one end, for use as an elastic attachment device. The zygomatic plate TAD appears to be much more successful in terms of its reasonably long‐term usefulness and has been shown to have a much lower failure rate than screws [22].

Fig. 2.8 An indirect anchorage system. (a) Extra‐oral view to show tipped occlusal plane due to anchorage loss during the attempted active eruption of the non‐responsive left maxillary canine. (b) Intra‐oral view of the same case shows the exposed canine ligated with elastic ligature to the first premolar. The space was held open by a steel tube tied between the incisor and premolar brackets. The extrusive force had resulted in the lateral open bite and cant of the occlusal plane. (c) Vertical intermaxillary bite‐closing (blue) elastics were used to support the anchorage of the maxillary arch. The mandibular canine bracket was ligated to a titanium screw temporary anchorage device with an elastic chain, to prevent unwanted reactive eruption of the lower teeth.

Zygomatic plates ( Figure 2.9a–c) may be used as the direct source of anchorage for intermaxillary and intramaxillary elastic attachment. Their placement is surgically more demanding than the bone anchor screw and they are generally inserted by an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Notwithstanding this disadvantage, the zygomatic plate has several inherent advantages over screw TADs. In the first place, since it is not placed on the alveolar ridge, it can be used as the base from which to apply traction to move teeth in the mesio‐distal plane over long distances, without impediment and without the need to alter their positions in the light of progress. Thus, if placed bilaterally in a young adult patient, they may be employed in place of the much‐hated, user‐contentious and under‐worn extra‐oral headgear for efficient horizontal distal movement of all the posterior teeth, en bloc , in the treatment of a class II case.

Fig. 2.9 Zygomatic plate. (a) An onplant plate. (b) The plate is held in place by three screws into the inferior surface of the zygomatic arch. (c) The extension portion is drawn through the edges of the fully replaced and resutured surgical flap.

Zygomatic plates also have excellent application in the vertical plane, as in the treatment of open bite cases that are due to or in association with forward tongue posture and abnormal swallowing behaviour. In these patients there is an increase in the height of the lower third of the face and the maxillary posterior teeth are over‐erupted, with elongated alveolar processes. To close the anterior open bite by extrusion of the incisor teeth is both counterproductive in terms of the face height and highly unstable. On the other hand, it is easy to apply vertically intrusive force to the posterior teeth and achieve a significant reduction in the lower facial height. It should be remembered that 1 mm of molar intrusion is reflected as 3 mm of anterior open bite closure, simply because the incisors are that much further away from the temporomandibular joint centre of the mandibular rotation. The plate should be supported by placing a transpalatal bar between the molars, to prevent buccal ‘rolling’ of these teeth that would occur by applying the intrusive force from the zygomatic onplant plate to an unsupported single molar. The intrusively directed force is then distributed to the bracketed posterior teeth through the agency of an archwire that must reach all the way to the last erupted molar on each side. Intrusion of posterior teeth, rather than extrusion of anterior teeth, may produce more stable results in what seems to offer a greater chance for correction of the abnormal tongue and swallowing anomalies. It should be understood that the prognosis is still in doubt but, if considerable clinical experience (in the declared absence of solid evidence) is anything to go by, probably improved.

Читать дальше