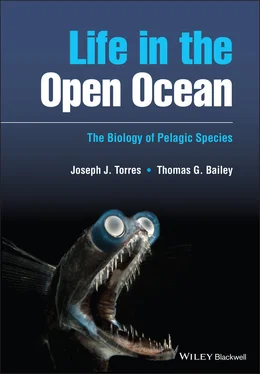

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

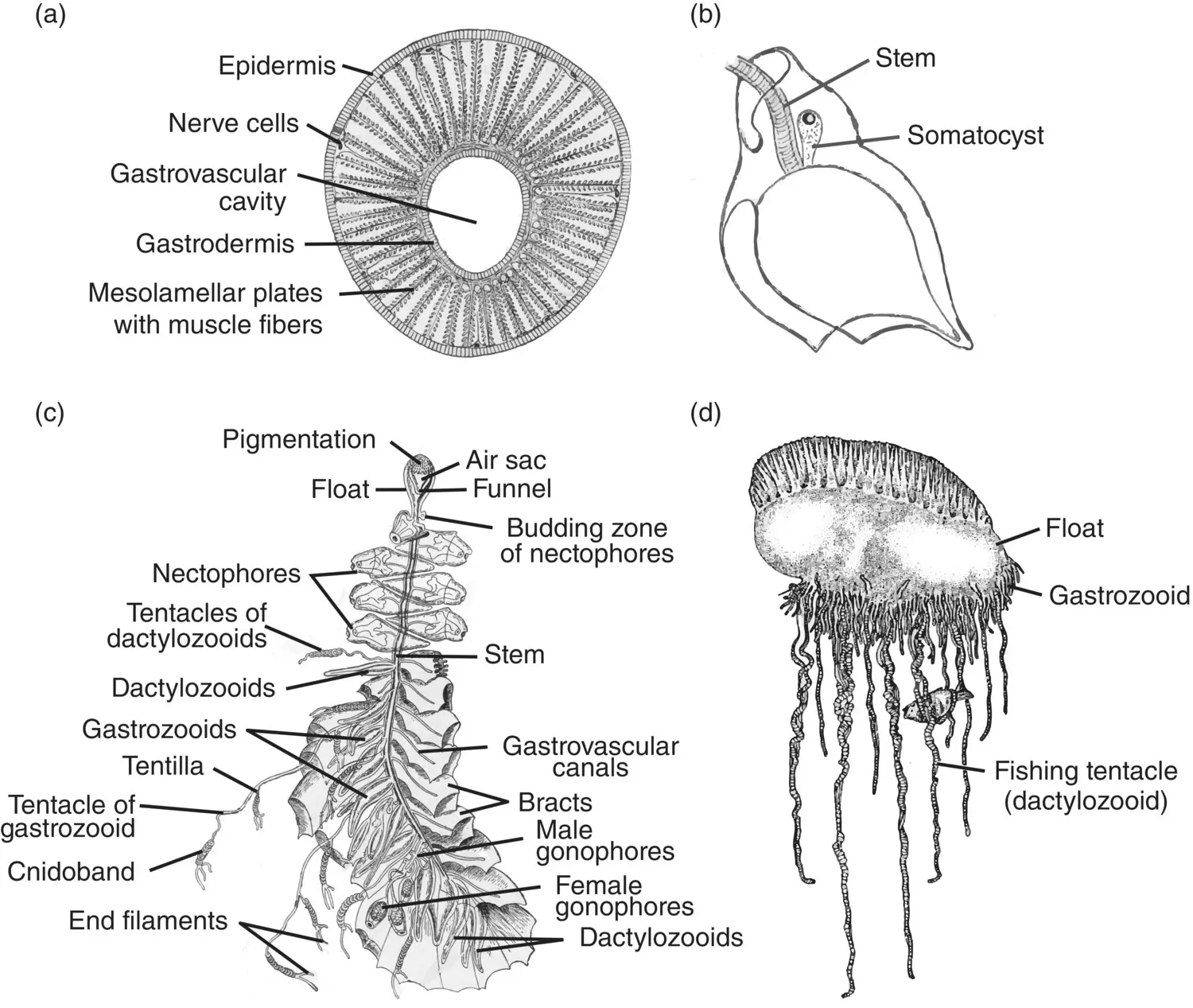

The stem is divided into two sections, the nectosome and siphosome (formerly siphonosome). In physonect siphonophores ( Figure 3.25c and d), the nectosome extends from the base of the float to the bottom of the swimming bells or nectophores. In the calycophorans, lacking a float, the nectosome is apical ( Figure 3.25e and f). The cystonects, which lack swimming bells altogether ( Figure 3.25a and b), have no nectosome at all.

Figure 3.30 Siphonophore colony structure. (a) Cross section of a siphonophore stem; (b) helmet‐shaped bract. (c) Colony of the physoncect Agalma . (d) Colony of the cystonect Physalia .

Sources: (a) Hyman (1940), figure 151 (p. 476); (b) Hyman (1940), figure 148 (p. 470); (c) Redrawn from Mayer (1900), plate 32; (d) Adapted from Brusca and Brusca (1990), figure 9 (p. 224).

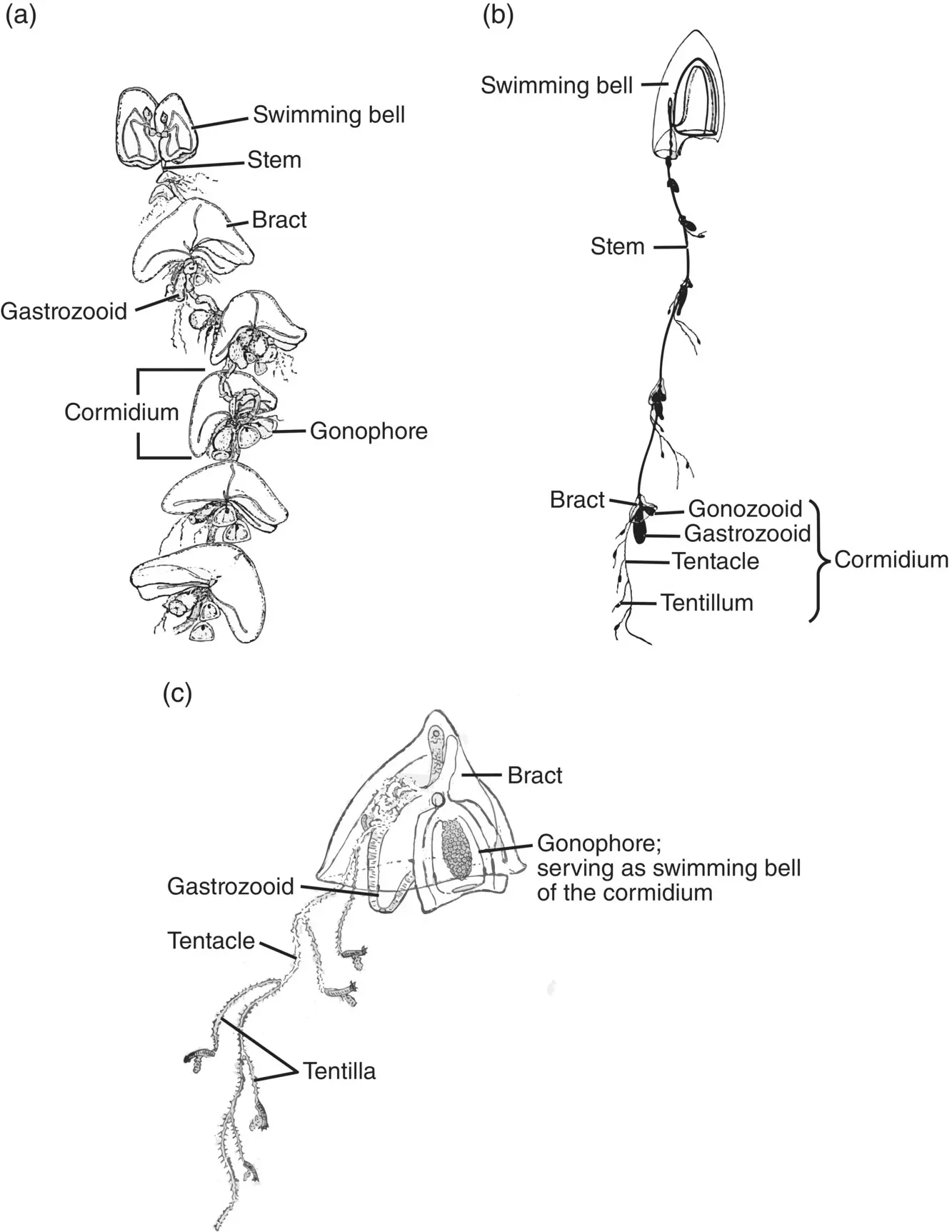

The remaining portion of the siphonophore stem is termed the siphosome. It makes up the majority of the stem in most species of physonects and calycophorans and the entire stem in the cystonects. Nectophores are budded from a zone of proliferation just below the float in the physonects. Similarly, the siphosome proliferates from a budding region just below the nectosome, producing repetitive groups of medusoid and polypoid persons called cormidia ( Figure 3.31). Within the Calycophorae, a cormidium often consists of a single gastrozooid, to the base of which is attached a tentacle along with one to several gonophores (Pugh 1999). Overlying the cormidium is a bract that has a characteristic shape and is often useful in identifying species ( Figure 3.31c). Cormidia within the physonects are larger and more complex, usually possessing several leaf‐like bracts, a gastrozooid, dactylozooids, and clusters of gonophores. The cystonects have simple cormidia consisting of a gastrozooid and clusters of gonophores radiating from a gonodendron or stalk. The cystonects have no bracts.

In the calycophorans, the terminal mature cormidia on the stem break away to form free‐swimming “eudoxids.” Until their true origins were resolved, eudoxids were thought to be a distinct group within the siphonophores (Hyman 1940). Limited propulsion within the eudoxids is achieved by the gastrozooids pinch‐hitting as nectophores. Shedding of cormidia for a brief free‐swimming existence is limited to the Calycophorae; neither the physonects nor the cystonects produce eudoxid s .

Figure 3.31 Siphonophore cormidia. (a) Calycophoran Nectocarmen antonioi . (b) Diphyid Muggiaea sp. (c) Enlarged cormidium of Muggiaea .

Sources: (a) Adapted from Alvarino (1983), figure 1 (p. 342); (b) Kaestner (1967), figure 4‐34 (p. 74); (c) Adapted from Hyman (1940), figure 150 (p. 174).

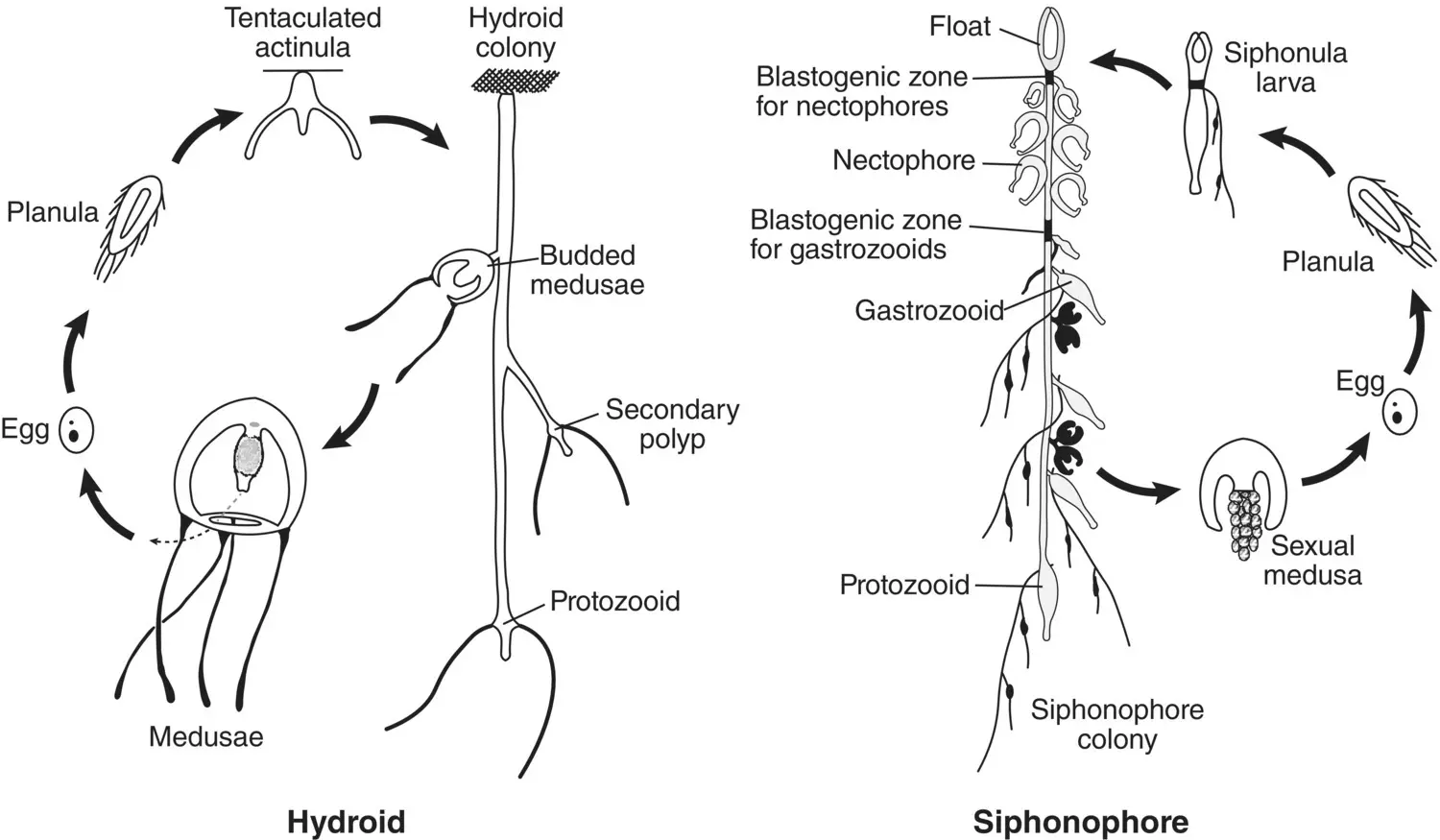

Life Histories

Development proceeds from a planula larva and differs between groups. In the physonects, the planula becomes a siphonula larva as summarized in Figure 3.32from Mackie (1986). The two budding zones produce the nectophores and the gastrozooids, gonophores, and bracts as the stem elongates during development. Development in the Calycophorae is somewhat different, with the initial production of a larval nectophore followed by development of the stem and gastrozooid. The larval nectophore is retained in some taxa (e.g. Sphaeronectes ) and lost in others (e.g. Hippopodius ). Early development in the cystonects is currently undescribed but defined budding zones beneath the float have been identified in both Physalia and Rhyzophysa .

The Siphonophore Conundrum

Is a siphonophore an individual or a colony? Siphonophores develop from a single egg, differentiating during development into a complex organism that is made up of parts that at some point in the distant past were probably free‐living polyps and medusae. How they came together and whether they are best considered as a colony or individual are questions that have piqued the interest of such luminaries as Ernst Haeckel, T. H. Huxley, E. O. Wilson, and S. J. Gould (cited in Mackie et al. 1987). However, for ease of understanding based on a lifetime of perspective, the observations of G. O. Mackie himself are the most cogent. In Mackie et al. (1987), he observed that “siphonophores … are linear in form with little branching, and are polarized, with a distinct anterior end. They are also bilaterally symmetrical. They grow by addition of modules at localized growth zones. The result is a high degree of determinacy of form.” Earlier (Mackie 1963), he offered this elegant observation.

Figure 3.32 Comparison of the life cycle of an agalmid siphonophore with that of an athecate hydroid.

Source: Reproduced from G. O. Mackie (1986), From Aggregates to Integrates: Physiological Aspects of Modularity in Colonial Animals, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences , 1986, Vol 313, No. 1159, page 179, by permission of the Royal Society.

They have developed colonialism to the point where it has provided them with a means of escaping the diploblastic body plan. The higher animals escaped these limitations by becoming triploblastic using the new layer, the mesoderm, to form organs. The siphonophores have reached the organ grade of construction by a different method – that of converting whole individuals into organs.

It is important to understand the concept that siphonophores function as highly coordinated individual organisms and not as a loosely collected gaggle of different zooids. Natural selection acts on the whole individual.

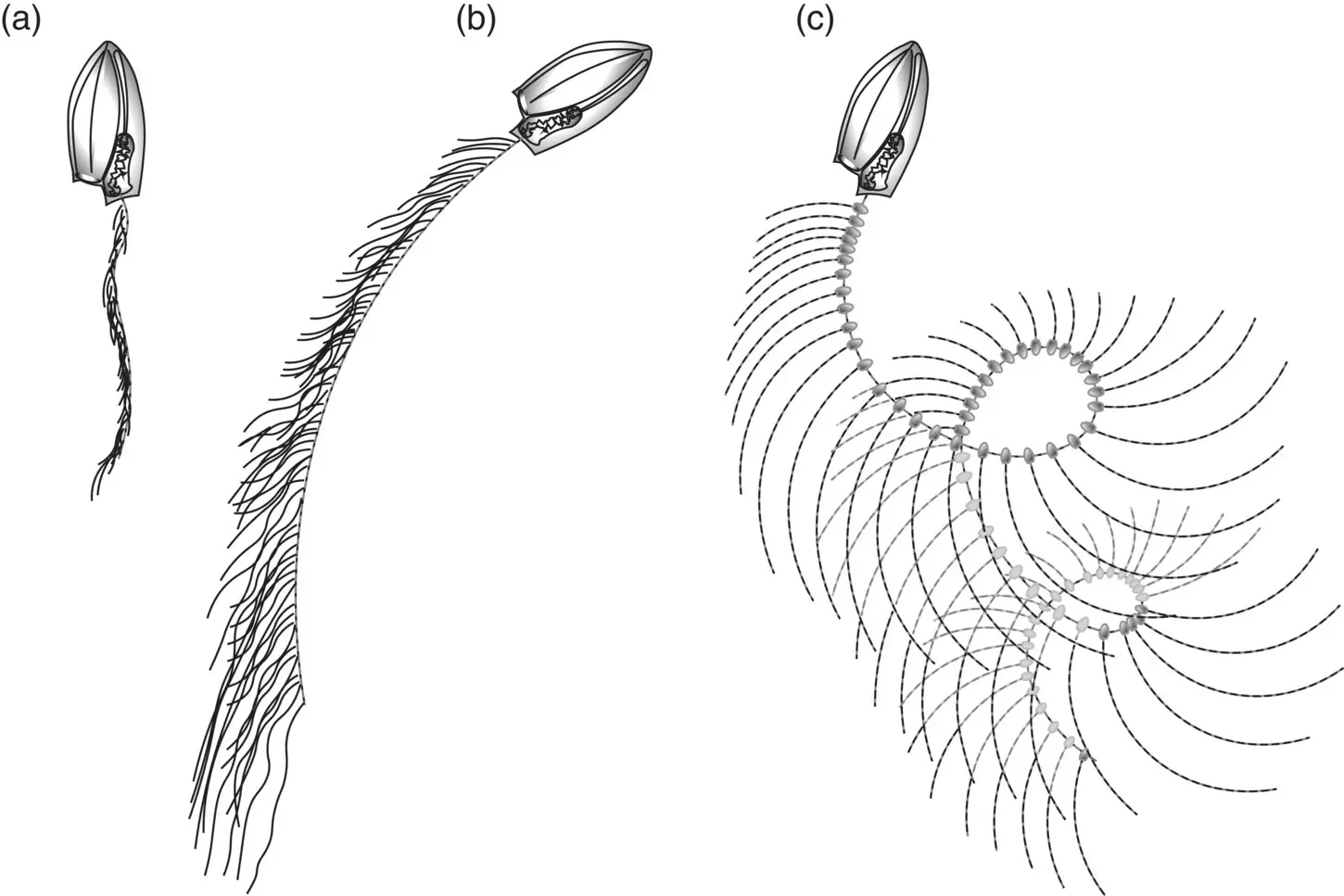

Figure 3.33 Cyclic fishing behavior and optimization of feeding space. (a) The Calycophoran Muggiaea atlantica begins a feeding cycle by swimming upward with contracted stem and tentacles; (b) it releases the stem and curtain of tentacles and swims in a circle; (c) swimming stops, with fully extended stem and tentacles; the stem then sinks under its own weight creating a corkscrew shape that slowly moves downward through the water column until the stem is vertical again, where it contracts, and the cycle begins again. This deployment cycle results in the fishing array moving through a maximum volume of water.

Feeding

Fishing Behavior

Unlike many of the medusae, siphonophores feed while drifting motionless, creating a “curtain of death” with their extended tentacles. Prey must blunder into the “curtain” for siphonophores to feed. Most calycophorans and physonects spread their tentacles for short bouts of swimming ( Figure 3.33) followed by longer periods of drift, usually several minutes in larger species. The frequency of swimming episodes for the purpose of tentacle‐reset scales roughly inversely with size, with the larger physonects swimming every few minutes and smaller calycophorans every minute or less. Species with large siphosomes, e.g. Apolemia at 20 m or greater, assume a horizontal position with the tentacles hanging down in a curtain. Swimming is less important for spreading the tentacles in the longer species (Mackie et al. 1987). Changes in the tentacle net happen gradually as structures sort themselves by density, sinking or rising with time. In some physonects, prey are tempted by periodic contractions of tentilla, mimicking the motion of zooplankters. In some cases, structures on the tentacle such as nematocyst batteries resemble “prey of the prey” and bring unwary prey species within the kill zone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.