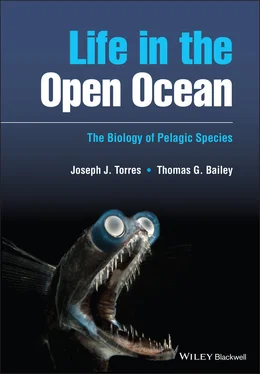

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

3 Reverse swimming, usually resulting from a stimulation to the float. In this case contraction of muscles at the velar openings directs the jet anteriorly, propelling the siphonophore to the rear.

Table 3.7 Abundance of siphonophores relative to other gelatinous zooplankton, estimated primarily by direct observation.

Source: Mackie et al. (1987), table 17 (pp. 242–243), with the permission of Academic Press (Elsevier).

| Location | Siphonophores | Medusae | Ctenophores | Method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gulf of Mexico(no./10 000 m 3) | Physonects | Calycophorans | ||||

| Spring (4) a | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 0 | 1.7 ± 2.2 | 10.2 ± 9.9 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1984) |

| Summer (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1984) |

| Fall (11) b | 8.8 ± 7.1 | <0.8 ± 1.0 | <8.7 ± 20.7 | 36.6 ± 51.0 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1984) |

| Winter (8) c | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 3.5 | 31.2 ± 53.8 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1984) |

| North Atlantic(no./10 000 m 3) | Total | Calycophorans | ||||

| Temperate (4) | 15.2 ± 24.5 | 27% d | 14.2 ± 13.4 | 38.5 ± 31.9 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1981) |

| Transitional (6) | 6.2 ± 10.4 | 62% d | 11.5 ± 9.7 | 24.7 ± 36.1 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1981) |

| Subtropical (7) | 8.0 ± 4.5 | 90%d d | 2.6 ± 3.0 | 2.1 ± 3.2 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1981) |

| Bahamas(no./10 000 m 3) | Total 8.3 ± 13.1 | 9.0 ± 7.8 | 52.3 ± 59.9 | Grid | Biggs et al. (1981) | |

| Southern California(no./m 3) | Polygastric | Eudoxids | ||||

| Sphaeronectes gracilis | 8.3 ± 4.6 | 6.3 ± 5.4 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | Net | Purcell and Kremer (1983) |

| Muggiaea atlantica | 6.7 ± 3.7 | 17.3 ± 11.5 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | Net | Purcell and Kremer (1983) |

| Apolemia sp. at 450 m | 0.2 ± 0.02 | — | 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | Submersible | Alldredge et al. (1984) |

| Strait of Georgia(no./m 3) | Polygastric | Eudoxids | ||||

| Muggiaea atlantica (October) | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 8.0 ± 3.8 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | Net | Purcell (1982) |

| Muggiaea atlantica (November) | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 7.2 ± 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.08 | Net | Mackie and Mills (1983) |

| Muggiaea atlantica (November) | 2.0 ± 2.6 | Common | 2.9–10 | 0.8–5.5 | Submersible | Mackie and Mills (1983) |

Numbers in parentheses following Gulf of Mexico seasons and North Atlantic zones are the number of SCUBA dives.

a Agalma, Physophora .

b Forskalia, Agalma, Athorybia, Cordagalma, Rosacea, Stephanophyes .

c Forskalia, Agalma, Nanomia, Cordagalma .

d Diphyes, Chelophyes, Rosacea .

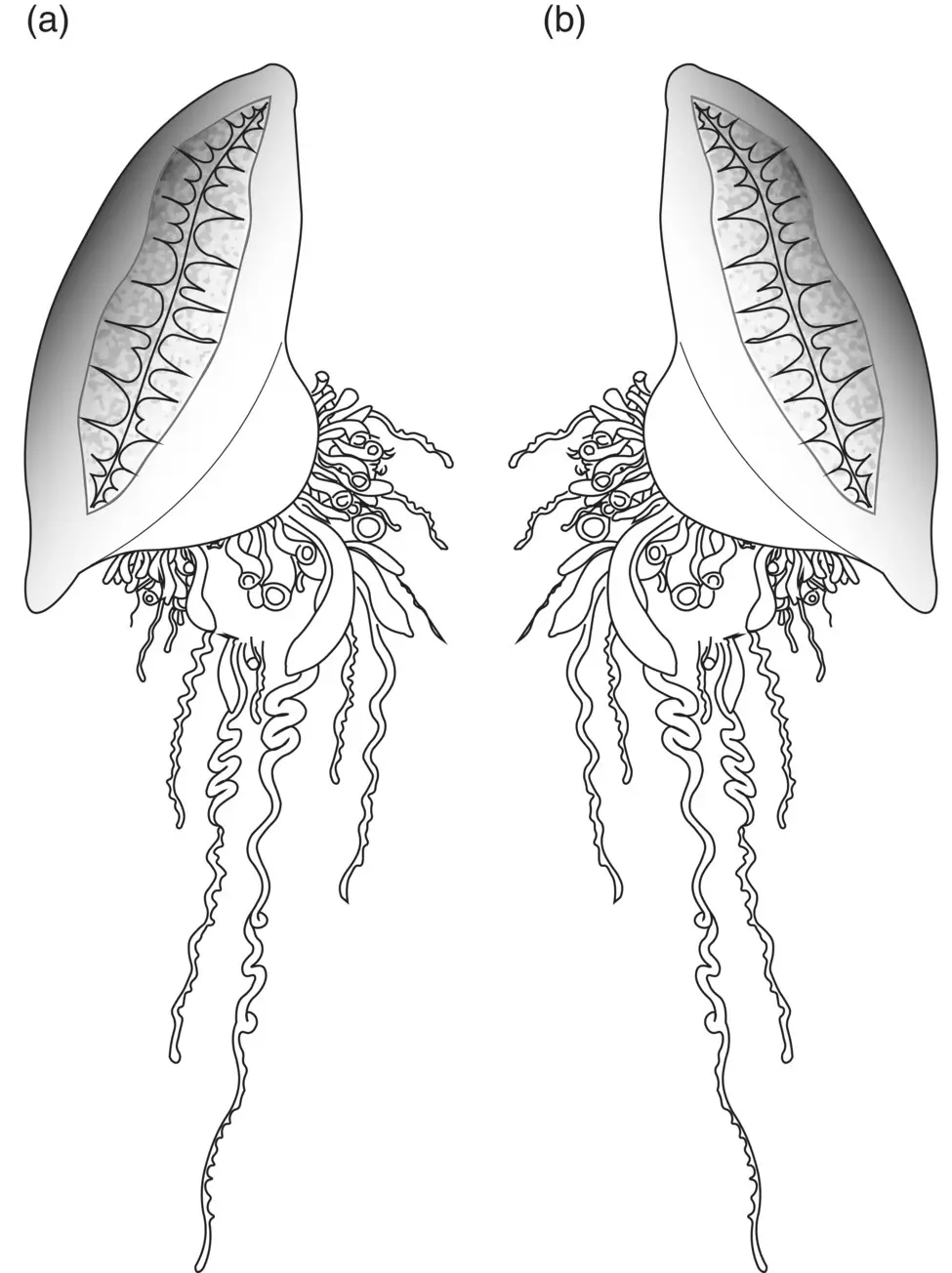

Figure 3.34 Dimorphism of Physalia . (a) Right handed (left sailing); (b) left handed (right sailing).

The calycophorans are the Olympic swimmers of the siphonophores. They lack a pneumophore and are often much smaller than the cystonects and physonects, but are, with a few exceptions, very capable swimmers. In the diphyids particularly, the nectophores have powerful swimming muscles and face directly backward, resembling a miniature spacecraft ( Figure 3.27d). Table 3.8gives the swimming speeds of several siphonophores. The diphyids may cruise using only the smaller posterior nectophore (Bone and Trueman 1982), keeping the larger anterior nectophore in reserve for escape. Keep in mind that for small species such as Chelophyes, the escape swimming velocities are many body lengths per second.

Buoyancy

As Mackie (1974) observed, “Cnidarians are fishermen, not hunters.” As a group, the siphonophores are the most committed to a fisherman’s lifestyle, the best examples being the very large species such as Apolemia, which are several meters in length. When observed from a submersible with their feeding tentacles extended, they even resemble a drift net, ambushing their prey in the dimly lit waters of the mesopelagic zone. Flotation is therefore particularly important to the siphonophores’ lifestyle. Neutral or positive buoyancy is achieved in two ways: by the use of floats, as in the cystonects and physonects, and by exclusion of heavy ions, as in the calycophorans.

Table 3.8 Swimming speeds (cm s −1) of siphonophores as estimated in situ by divers.

Source: Field Studies of Fishing, Feeding, and Digestion in Siphonophores, D. C. Biggs, Marine & Freshwater Behaviour & Physiology, 1977, table 1 (p. 263). Reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com).

| Species | Number measured | Undisturbed (“normal” speed) | Escape speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agalma okeni | 27 | 2–5 | 10–13 |

| Nanomia bijuga | 2 | — | 25 |

| Forskalia spp. | 10 | 1–3 | 2–5 |

| Stephanophyes superba | 3 | 10–15 | — |

| Rosacea cymbiformis | 5 | 1–3 | 3 |

| Sulculeolaria monoica | 5 | 2–5 | 12–16 |

| Chelophyes appendiculata | 6 | 7–16 | 23 |

| Diphyes dispar | 3 | 1–3 | 5–10 |

The cystonects are entirely dependent on their float for buoyancy ( Figure 3.35a). For genera such as Rhysophysa that remain in the midwater, the ability to adjust their position in the water column may come either from secretion of gas into the float or release of gas from it. An apical pore in the float allows for gas release. In Physalia , the large pneumophore is kept inflated as it fishes from the surface. In both species the gas within the float is carbon monoxide, secreted by gas glands intimately associated with the float.

The physonects depend to a varying degree on the float for buoyancy. Streamlined genera such as Nanomia that have much of their mass in the nectophores and little gelatinous tissue below them ( Figure 3.35b) are apparently quite dependent on the float to maintain their position in the midwater, being negatively buoyant without it. In contrast, genera such as Agalma with considerable gelatinous tissue below the nectophores ( Figure 3.35c) depend to a much greater degree on the lift provided by the gelatinous tissue.

Calycophorans, having no float, must swim constantly, sink, or rely on their own tissues for lift. Jacobs (1937) first demonstrated that the gelatinous tissues of siphonophores provided lift, and later studies (Robertson 1949; Bidigare and Biggs 1980) provided the mechanism: selective replacement of heavier ions within the tissue, notably the replacement of sulfate with chloride. The lift provided by sulfate exclusion is sufficient in siphonophores and other nearly neutral gelatinous species to enable station‐keeping in the water column. It is worth noting that other important pelagic groups, such as the Crustacea (e.g. Sanders and Childress 1988), also exploit sulfate exclusion as a buoyancy mechanism.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.