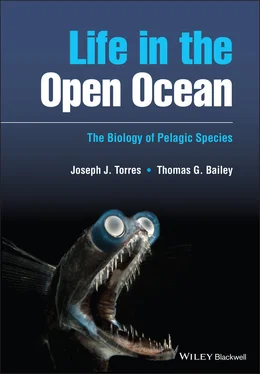

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Vertical Distribution

As truly open‐ocean species, siphonophores are found throughout the water column from the pleustonic surface layers to very great depth (8000 m, Vinogradov 1970). Though vertical distributions for individual species can be extensive, most siphonophores exhibit depth ranges over which they are typically most abundant. Those ranges are the same as seen with most other open‐ocean taxa: epipelagic (0–250 m), mesopelagic (250–1000 m), and bathypelagic (>1000 m) (Pugh 1999).

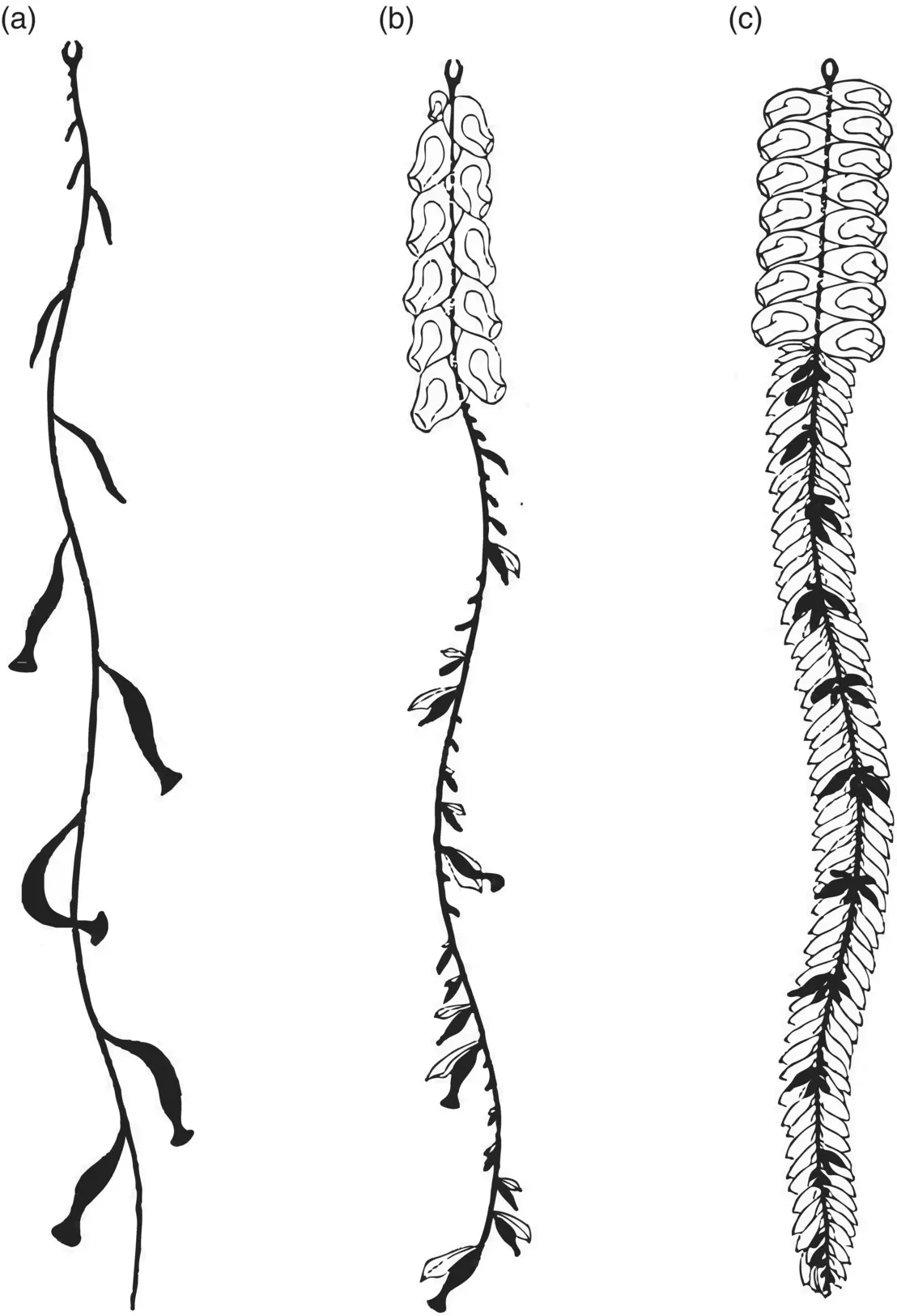

Figure 3.35 Degrees of dependence on gelatinous parts for flotation. (a) Rhizophysa filiformis is completely dependent on the apical float for support and lacks gelatinous parts; (b) Nanomia bijuga has gelatinous nectophores and bracts but is largely dependent on the float; (c) Agalma elegans is buoyed mainly by gelatinous parts with the float only supporting a short anterior portion of the stem.

Source: Jacobs (1937), figure 7 (p. 594).

Siphonophores are quite delicate, particularly prone to damage from midwater trawls and even gentle plankton nets. The damage usually involves breaking the animal into its constituent parts, and with particularly delicate forms, the damage may preclude identification altogether. Delicate forms can literally pass through the meshes of a scientific net. Thus, conclusions drawn from a net sampling survey will tend to be biased toward the more robust species. Surveys done primarily with visual observations, by either SCUBA or submersible, will also have bias, usually toward slower moving, larger species. Both types of sampling have their shortcomings, but without question, far more sampling has been done with nets. Trawling techniques have been around longer, trawls sample greater volumes, and they are far cheaper to execute. It is important to recognize the pros and cons of all sampling methodologies and to take away from each what is most useful.

Pugh (1999) observed that calycophophoran species tend to dominate in net samples, but that over 70% of the specimens collected by submersibles are the larger, more delicate, and more highly pigmented physonects. An interesting, though disturbing, corollary to his observations on relative numbers was that about half of the physonects collected by submersibles were new to science. Clearly there remains a lot to learn about the siphonophores.

Data from Pugh (1999) for 93 widely distributed Atlantic siphonophore species are summarized in Table 3.9. Forty‐one species are considered to be mainly epipelagic (0–250 m), 17 are epipelagic–upper mesopelagic (<100 m to >250 m), 31 are mesopelagic (200–1000 m), and 4 are bathypelagic (>1000 m). The best information to date suggests that the majority of siphonophores reside in the most productive upper 250 m of the ocean.

Table 3.9 Vertical distribution of Siphonophore species in the South Atlantic.

Source: From the data in Pugh (1999).

| Primary depth range | Number of species | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Order Cystonectae | Order Physonectae | Order Calycophorae | |

| Epipelagic (0–250 m) | 3 | 4 | 34 |

| Epi‐upper Mesopelagic (<100 m to >250 m) | 0 | 5 | 12 |

| Mesopelagic (200–1000 m) | 0 | 7 | 24 |

| Bathypelagic (>1000 m) | 0 | 0 | 4 |

Diurnal Vertical Migration

As discussed, swimming ability within the siphonophores varies widely. The idea that siphonophore populations move up to the surface at dusk and back to depth at dawn in response to the waning and waxing illumination in near‐surface waters is not a compelling one, especially for the suborders with more limited mobility. Nonetheless, there is a substantial amount of data for many species that suggest precisely that. Moore (1949, 1953) reported vertical excursions of 30–40 m for many species of calycophorans in both the Florida current and in the vicinity of Bermuda on a day–night basis. Similar results were obtained by Musayeva (1976) for calycophorans in the Sulu Sea.

An alternative to a directed vertical migration triggered by sunset and sunrise is a slowly undulating change in vertical profile over a 24‐hour period (Pugh 1977). Siphonophores gradually move up and down with the changing photoperiod. This sinusoidal pattern of migration would explain the unusual depth profiles obtained for some weakly swimming species such as Hippopodius hippopus . The theory is still somewhat speculative.

Without question, a changing vertical distribution over the diel cycle is a characteristic of many siphonophore species. However, even among the calycophorans the vertical excursions are usually quite limited in scope (<50 m), a situation to be expected in an order that is morphologically adapted more for ambush predation than long‐distance swimming. Because of their float, the physonects are not only good acoustic targets, they face the same problems that fish with swimbladders do when moving vertically: expansion and compression of gas in their flotation system when moving up and down in the water column.

Geographical Distribution

Siphonophores are pan‐oceanic; they are found from the equator to the polar oceans in all the major ocean basins. Mackie et al. (1987) concluded that siphonophore distributions coincide reasonably well with the biomes and provinces described in the biogeography literature (e.g. Briggs 1995; Longhurst 1998), which in turn coincide with the earth’s major climatic zones. The best data describing faunal relationships with latitude and longitude come from Atlantic waters. Margulis (1976) recognized seven faunal groups among the siphonophores of the Atlantic, which correspond well to the latitudinal zones of Briggs ( Figure 3.36): Arctic species, Northern Boreal species (cf. cold temperate), Antarctic species, Bipolar species (found in the Arctic and Antarctic), Tropical species (which include equatorial and warm temperate components), Eurybiotic species (those which live in all biogeographic areas), and Neritic species. An excellent compendium of Atlantic species’ latitudinal ranges may be found in Pugh (1999). Most (60 of 96 species) were very wide‐ranging, with distributions encompassing 80° of latitude or more, roughly half on each side of the equator.

Mackie et al. (1987) provide a summary of diversity and numbers for 21 common species of calycophoran siphonophores in the North Atlantic. The data show a peak in both numbers and diversity at about 18 °N with a gradual decline in species numbers further north. A second peak in abundance is obvious between 40 and 53 °N.

Organization and Sensory Mechanisms

No sensory apparatus has been detected in the siphonophores, i.e. no ocelli, statocysts, or mechanoreceptors such as those observed in the medusae. However, siphonophores are sensitive to touch, light, chemicals, and, in some cases, to waterborne vibration. How? It is likely that the nerves themselves act as receptors although mechanisms effecting the receptor‐like responses are undescribed.

Two types of conduction are recognized in the siphonophores, epithelial and neural. Both contribute to coordinated movement and responses. Epithelial conduction is similar to the spread of depolarization in myogenic hearts and is present in the nectophores of physonects and calycophorans. Epithelial conduction was effectively demonstrated in Nanomia when its nectophores remained coordinated after severing their nervous connection to the stem (Mackie 1964).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.