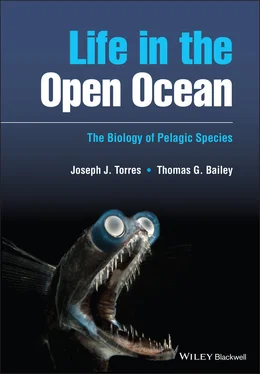

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

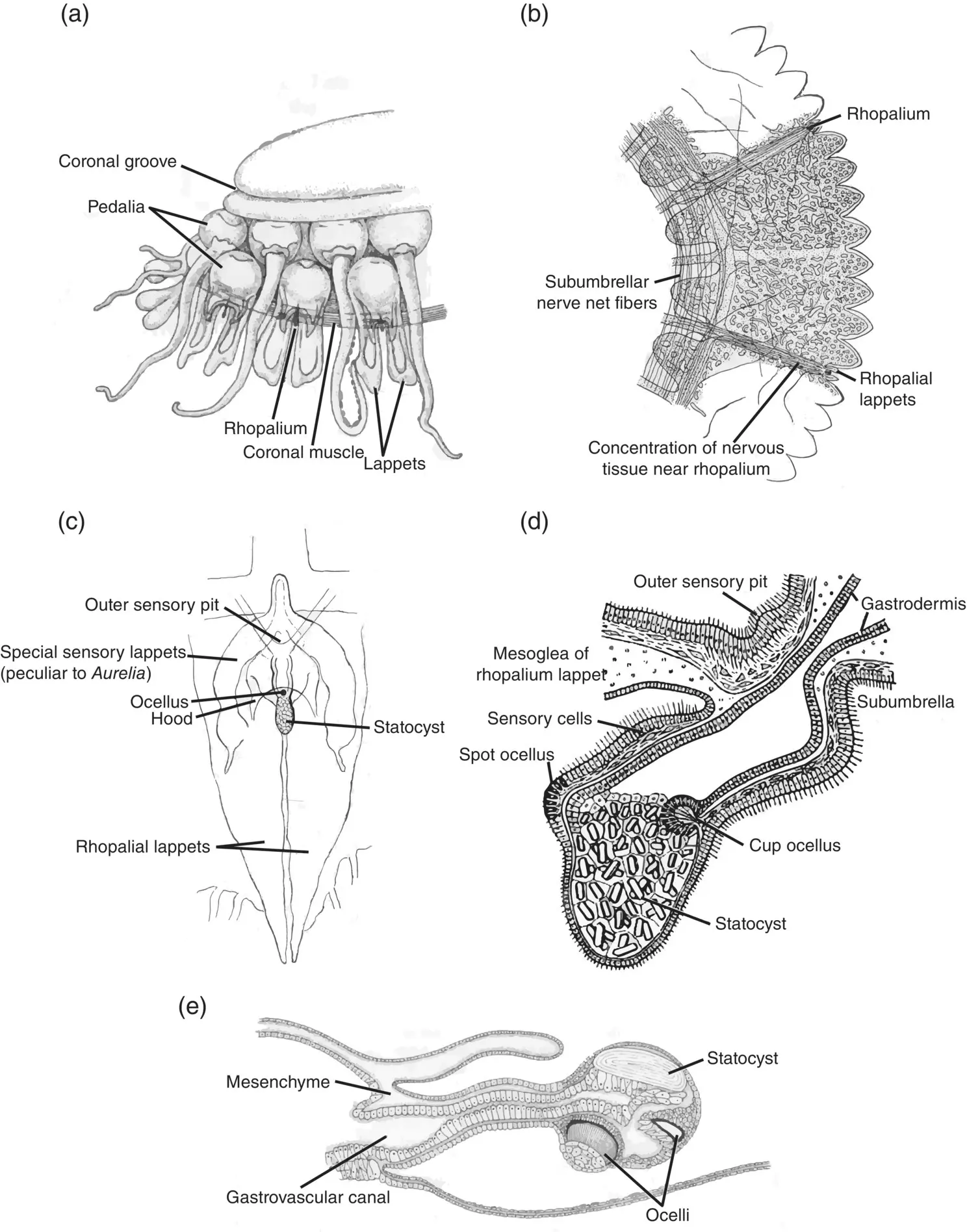

Figure 3.23 Sensory mechanisms: rhopalia. (a) Position of the rhopalia of the scyphomedusa Atolla , located between the marginal lappets. (b) Sector of the bell of Rhizostoma, showing nerve plexus and gastrovascular network (stippled); (c) rhopalium and surrounding structures in Aurelia . (d) Section of the rhopalium of Aurelia aurita ; diameter at ocelli is 0.4 mm. (e) section of a cubomedusan rhopalium.

Sources: (a) Redrawn from Maas (1904), plate IV; (b and c) Hyman (1940), figure 163 (p. 504); (d) Kaestner (1967), figure 5‐4 (p. 91); (e) Redrawn from Mayer (1910), Vol III, plate 56.

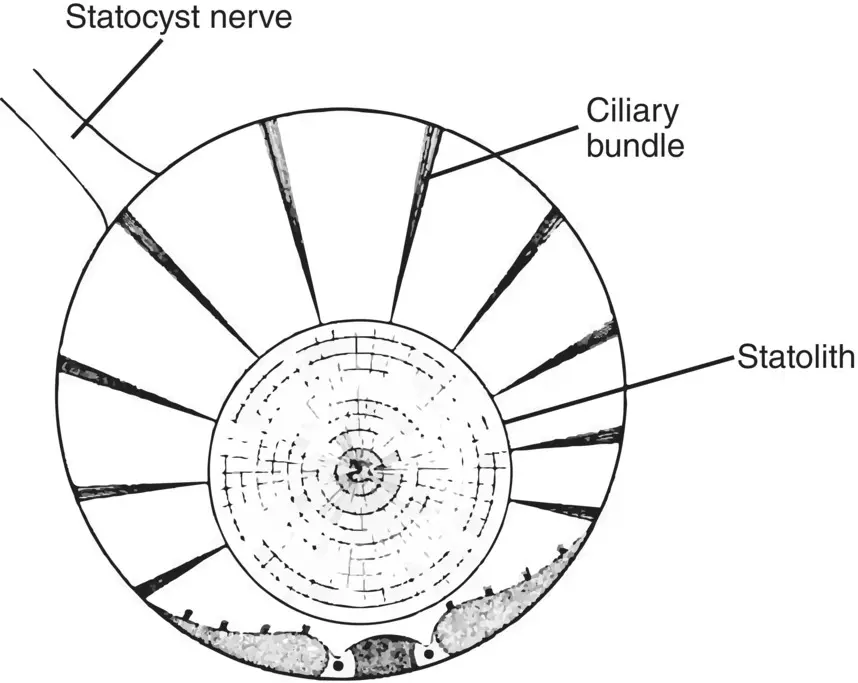

Statocysts, or equilibrium sensors, are an example of a class of sensory receptors known as mechanoreceptors. At their most sophisticated, mechanoreceptors detect vibration and sound using the same basic principles we observe in organs of equilibrium. The basic structure of a statocyst is depicted in Figure 3.24. In it is a dense body, or statolith, which can be thought of as a stone or concretion secreted by the animal. The sensory epithelium is made up of cells with hair‐like projections (“hair cells”) that are sensitive to deformation by the statolith. A change in position of the animal will change the position of the statolith on the sensory epithelium, providing information on attitude and equilibrium of the whole animal. Hair cells are present in virtually all types of mechanoreceptors, including those of our own inner ear.

The last type of sensory modality, chemoreception, has been inferred from the behavior of medusae, specifically by the orientation of medusae toward aggregations of prey or even to water that has been conditioned by the presence of prey (Hamner 1995). No specific structures associated with chemoreception have been identified yet, but the fact that cnidarians will show feeding behavior in response to chemical stimuli such as prey homogenates and the tripeptide reduced glutathione has been known for decades.

Sensory mechanisms provide an animal’s windows into the physical world. The most telling evidence for the presence or absence of a sensory modality is in a species’ behavior. Even if a sense such as touch does not have a discrete, obvious, and easily identified receptor, if a medusa responds to touch, e.g. by suddenly retracting its tentacles, the animal is obviously capable of discriminating touch. Even in more advanced species such as the vertebrates, sensory mechanisms exist that are not easily discriminated, those for heat and cold being two. As different open‐ocean dwellers are described in further chapters, we will observe more sophisticated sensory organs in more sophisticated taxa. Sensory mechanisms, and neural processes in general, are exquisitely complex.

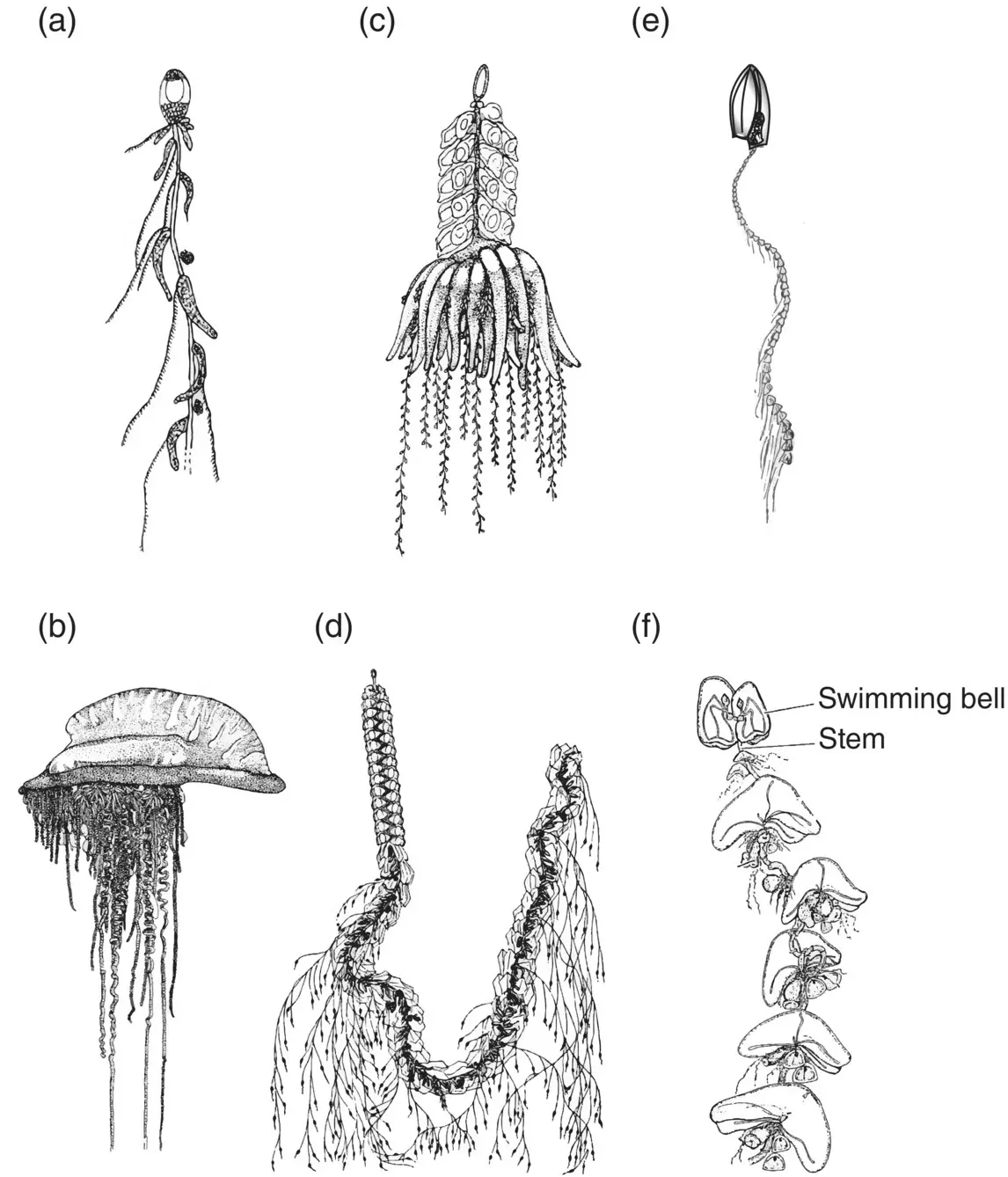

The Siphonophores

The Siphonophora comprise an order in the class Hydrozoa, subclass Hydroidolina, as shown in the classification scheme. They are quite distinct, differing from their hydrozoan brethren and the remainder of the pelagic Cnidaria in general morphology and basic organization. Three major biological groups are widely recognized within the Siphonophora, but there are disagreements about their relative taxonomic rank within the order. In this case we are following the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) and many decades of history in placing them each in their own suborder. The three suborders are the Cystonectae the Physonectae, and the Calycophorae ( Figure 3.25). Altogether, the three suborders contain about 190 species, with the lion’s share of them, about 60%, in the suborder Calycophorae. Suborders within the siphonophores are discriminated initially by the presence or absence of a gas‐filled float or pneumophore. The suborders Cystonectae and Physonectae ( Figure 3.25a–d) both have a gas‐filled float, whereas the calycophorans do not ( Figure 3.25e and f). The second division for classification is in the presence of swimming bells beneath the float. The physonects have swimming bells, or nectophores, beneath the float; cystonects do not. Table 3.5is a synopsis of siphonophore classification. The siphonophores are more diverse at the family level than the rest of the Cnidaria.

Figure 3.24 Basic statocyst structure showing the calcium carbonate statolith resting on sensitive sensory cells, which respond to changes in position of the statolith.

Source: Tschachotin (1908), text figure 5 (p. 358).

Siphonophores are possibly the most confusing group in the animal kingdom. A free‐floating individual siphonophore is considered to be a colony of various individuals working together to feed, reproduce, and move about, and within each siphonophore colony are individuals with either medusoid or polypoid affinities. Once the concept of a floating colony of individuals working together as a single entity is mastered, a lexicon of terminology replete with historical changes needs to be assimilated before life‐history questions can be resolved. How does a colony develop from a single propagule? How do the various bits and pieces work together? Fortunately, some of the great minds in the history of biology have been fascinated by the group: Ernst Haeckel for example. And two very cogent reviews of the group by some of the best talent in gelatinous zooplankton biology (Mackie et al. 1987; Pugh 1999) are invaluable resources.

Terminology and Affinities of Siphonophore “Persons”

As Hyman (1940) notes, siphonophore colonies represent the highest degree of polymorphism in the Cnidaria. Terminology is critical to understanding siphonophores. Individuals within the siphonophore colony are known usually as “zooids” or “persons.” To begin, it is best to differentiate between the polypoid and medusoid forms making up the individuals in the siphonophore colony.

Polypoid zooids comprise three basic types: the gastrozooids, the dactylozooids, and the gonozooids ( Figure 3.26).

Figure 3.25 Examples of the three suborders of siphonophores. Cystonectae; (a) Rhizophysa and (b) Physalia , respectively. Physonectae; (c) Physophora and (d) Agalma , respectively. Calycophorae; (e) Muggiaea and (f) Nectocarmen , respectively.

Sources: (a) Pugh (1999), figure 3.2(p. 495); (b) Pugh (1999), figure 3.1(p. 495); (c) Pugh (1999), figure 3.16(p. 497); (d) Kaestner (1967), figure 4‐35 (p.75); (f) Adapted from Alvarino (1983), figure 1 (p. 342).

Gastrozooids are the only members of a siphonophore colony that can ingest food and are sometimes called “siphons.” The name siphonophore means “siphon‐bearer,” a siphon in Greek and Latin being a tube or pipe. Gastrozooids have a tubular polyp‐like shape but no fringing tentacles at the mouth. Instead, a single long highly contractile tentacle emanates from the base with many side branches or tentilla ( Figure 3.26a). The tentilla often terminate in distinctive structures thought to resemble the “prey of the prey” of the siphonophore, as well as in nematocyst batteries.

Dactylozooids resemble gastrozooids without a mouth ( Figure 3.26b). They usually have a simple basal tentacle instead of one bearing tentilla and are often called palpons. Dactylozooids may sometimes resemble nothing more than a large, particularly robust tentacle, particularly when they are associated with gonozooids. In those cases they are known as gonopalpons.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.