Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Georges Bank is a shallow (45 m depth) hummock in the Gulf of Maine, USA, made famous by its former bountiful harvests of cod ( Gadus morhua ), sadly now depleted. The area was the subject of an intensive multidisciplinary 1990–2000 oceanographic study as part of the international GLOBEC ( GLOB al Ocean EC osystem Dynamics) program, funded by the USA’s National Science Foundation. The mission of GLOBEC was to describe the interaction of physical and biological processes in the life history of important species. In the case of George’s Bank, the target species was cod.

A GLOBEC sampling cruise in May of 1994 revealed large numbers of suspended hydroid colonies in the zooplankton over the shallows of Georges Bank (Madin et al. 1996). The colonies were typically fragments of 2–5 polyps each, were widely distributed over the bank, and were the overwhelming dominant component of the net‐caught zooplankton, reaching densities of 10 000 m −3in the water column and 25 000 m− 3nearer the bottom. Colonies were found to be the polypoid life stage of the hydromedusan genus Clytia , predominantly Clytia gracilis , which normally grows attached to rocks, seaweed, or other available benthic substrate. The polyps suspended in the water column instead of being attached to substrate were not only alive, they were actively hunting. Examination of gut contents and shipboard experiments revealed that the hydroids were catching and digesting larval cod as well as copepod eggs and larvae. Madin et al. (1996) estimated that the hydroids were capable of ingesting half the daily production of copepod eggs and a quarter of the standing stock of copepod larvae per day: an impressive figure for a benthic life stage.

Feeding in the Cubomedusae

The cubomedusae are well known as having a potent sting, particularly the Australian sea wasp Chyronex fleckeri , a large jelly (football‐sized bell and bigger) that can cause open welts in humans and, with severe stings, even respiratory distress and death. The virulence of cubomedusan venom allows the group to take large prey.

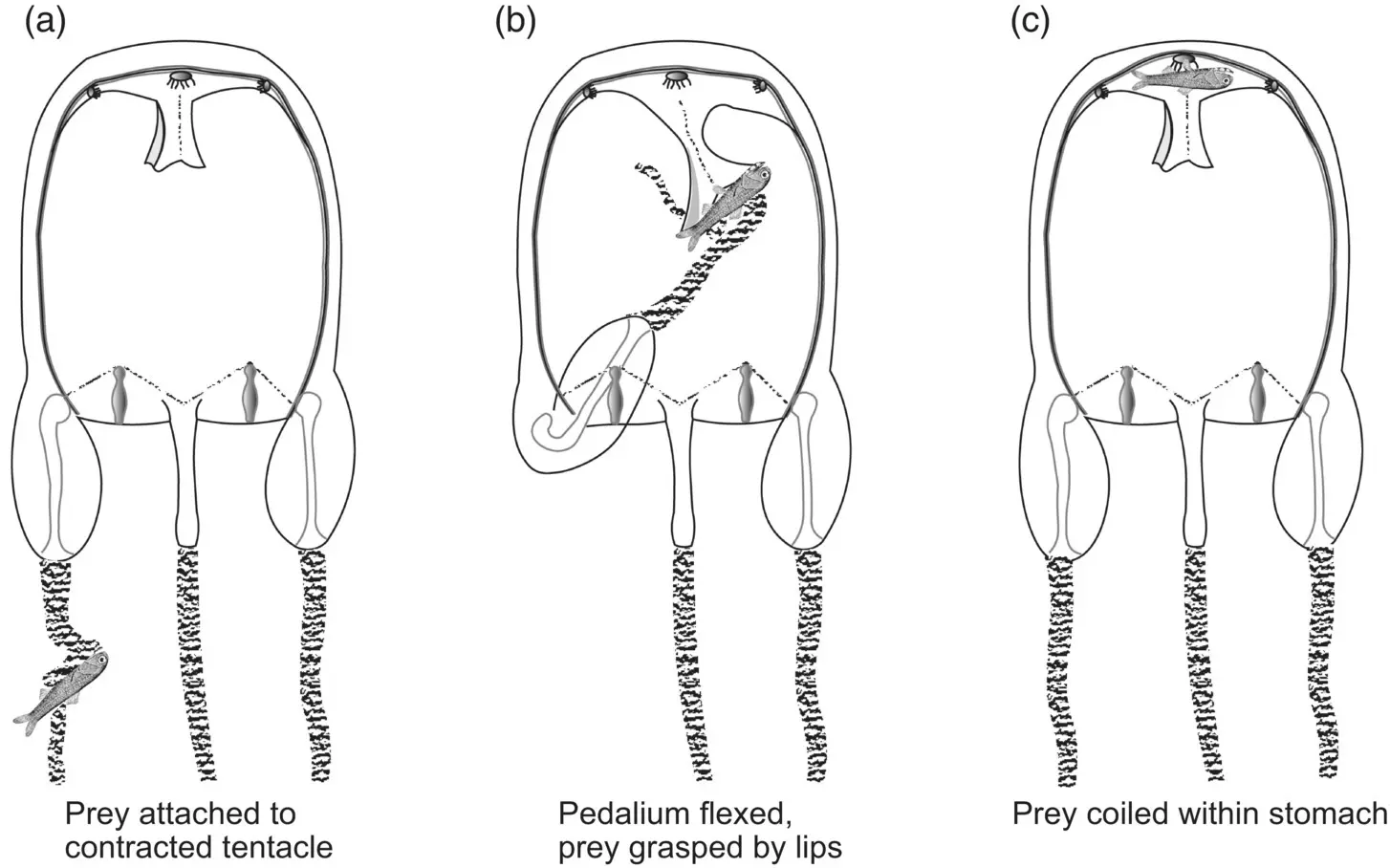

Figure 3.19 Prey capture and ingestion in Carybdea marsupialis . (a) Prey capture; (b) Prey transfer to mouth; (c) Prey ingestion.

Source: Adapted from Larson (1976).

The importance of a strong venom and nematocyst system in cubomedusae is underscored by a description of the feeding behavior of the Caribbean cubomedusa Carybdea marsupialis (Larson 1976). Carybdea has four robust tentacles that can reach 30 cm in length when extended or about 10 times the height of the bell. Prey are captured on the tentacles by annular nematocyst batteries that paralyze and trap the prey on the tentacle with considerable adhesive force. The “sticking power” of the nematocysts is so strong that fish too large for Carybdea to handle must break the tentacle to escape. Once the prey is subdued, it is conveyed into the bell cavity and onward to the digestive system by an inward flexion of the tentacle ( Figure 3.19). The outer digestive region, or manubrium, is short, and its outer lips are prehensile, so that when a prey item is contacted, it is quickly engulfed.

Though data are limited on the diets of cubomedusae, the little data available suggest a varied menu including polychaetes and small fish as well as the more typical small crustaceans ( Table 3.4). Observations reported in Larson (1976) suggested some selectivity for fish by Carybdea marsupialis .

Locomotion

Medusae are among the very few aquatic taxa that swim using jet propulsion. Though “jet propulsion” does not necessarily invoke the mental picture of a slowly swimming medusa, the medusae, the squids and octopi, and the salps and doliolids are major marine taxa that swim using jet propulsion. Scallops also use it to escape from starfish predators by rapidly closing their valves to expel a jet of water, allowing brief forays into the water column.

Table 3.4 Diets of cubomedusae.

Source: Larson (1976), table 2 (p. 242). Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature Customer Service Centre GmbH, Cubomedusae Feeding, author R. J. Larson, in Coelenterate Ecology and Behavior, G.O. Mackie editor, 1976.

| Species | Coelenteron contents | References |

|---|---|---|

| Carybdea alata | Polychaetes, mysids, crab megalopae | Larson (unpublished) |

| Carybdea marsupialis | Polychaetes, misc. crustaceans (copepods, isopods, amphipods, stomatopod larvae, mysids, caridean shrimp and larvae, crab zoeae), chaetognaths, fish | Berger (1900), Larson (unpublished) |

| Carybdea rastoni | Polychaetes, mysids, fish | Gladfelter (1973), Ishida (1936), Larson (unpublished), Uchida (1929) |

| Chiropsalmus quadrumanus | Misc. crustaceans (amphipods, cumaceans, stomatopod larvae, Lucifer spp., caridean shrimp, crab larvae), fish | Larson (unpublished), Phillips and Burke (1970), Phillips et al. (1969) |

| Chiropsalmus quadrigatus and Chironex fleckeri | Caridean shrimp ( Acetes spp.), other small crustaceans, fish | Barnes (1966) |

| Tripedalia cystophora | Copepods ( Oithona spp.) | Larson (unpublished) |

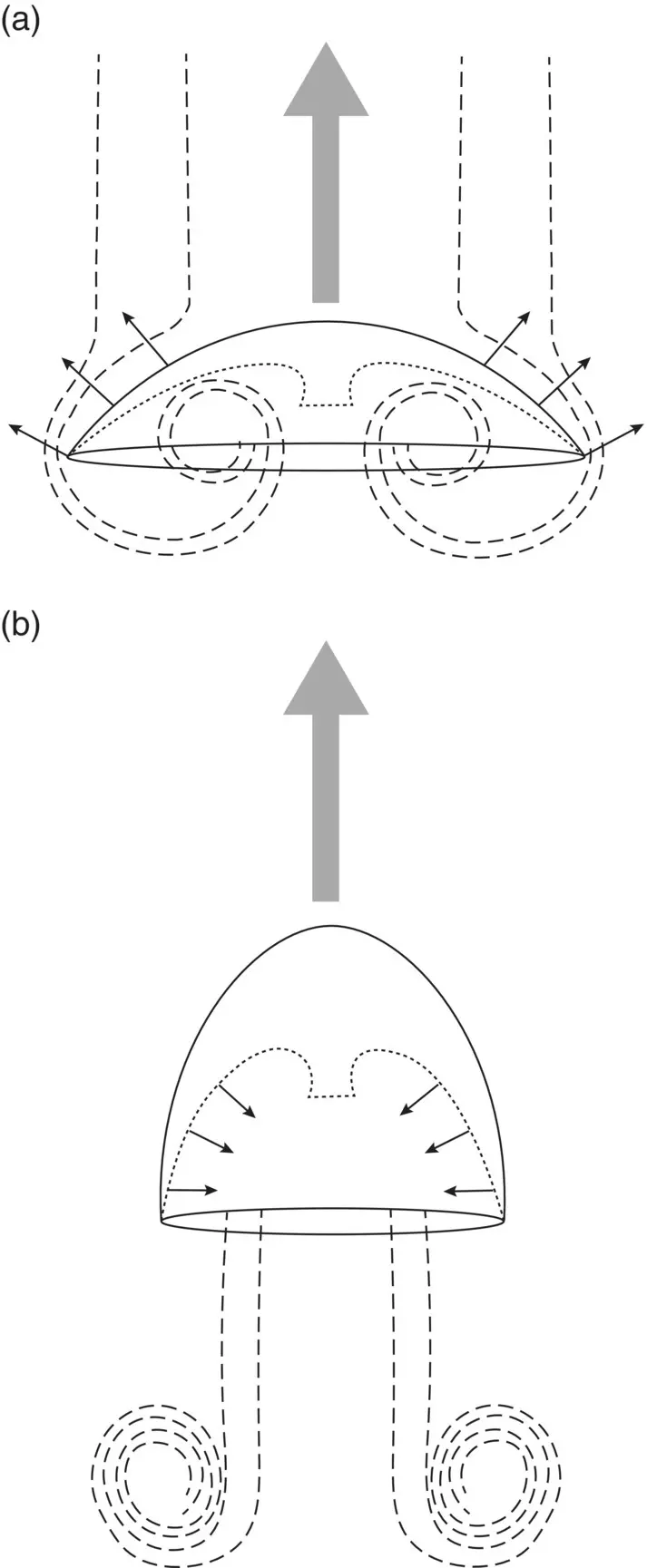

Medusae swim by ejecting the volume enclosed by the bell toward the rear with a forceful contraction, propelling the animal forward ( Figure 3.20). Alternate rhythmic contraction of muscles to propel the jet and elastic recoil of mesoglea to refill the jet allow a medusa to make its way forward. The basic locomotory system thus comprises the swimming muscles, the deformable mesoglea that gives the swimming bell its elastic character, and a pacemaker that sets the rhythm and assures that contraction is synchronous over the bell.

The swimming muscles are of two basic types: radial muscles aligned in the same axis as the radial canals, that is, from the center to the periphery of the bell; and the coronal muscles that form a ring parallel to the margin ( Figure 3.21). In the Scyphozoa, swimming is usually initiated by a contraction of the radial muscles, causing the bell to shorten, followed by a contraction of the coronal musculature, which cinches up the margin and forces a jet of water out the bell. In the Hydrozoa, swimming is effected in much the same way with the exception that the presence of a velum, or skirt, gives more direction to the stream of the jet. Direction of the swimming hydromedusa can thus be manipulated by differential contraction of the radial muscles.

Figure 3.20 Jet propulsion in medusae. (a) Bell expansion and water intake; (b) bell contraction with water expulsion. Direction of motion is indicated by the large arrows.

Unlike the continuous movement of fishes and shrimp, medusan swimming is intermittent in nature, alternating periods of thrust with the refilling of the jet. We know that in most cases the movement is fairly slow, with velocities of 5 cm s −1or less, but how efficient is it? The answer is, not very. A few studies have examined the swimming performance of medusae using both modeling (Daniel 1983) and empirical approaches (Daniel 1985). Daniel calculated a Froude efficiency of about 10% for the hydromedusa Gonionemus , which means that the work done by the muscle in creating the jet was about 10 times the drag that the jet needed to overcome in order to propel the medusa through the water (Alexander 2003). A medusa expends about 10 times as much effort to move through water as does a fish.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.