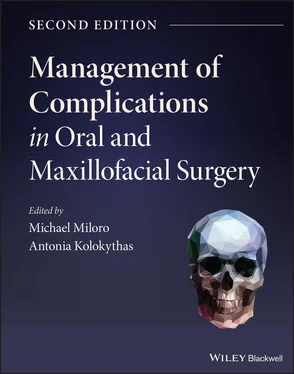

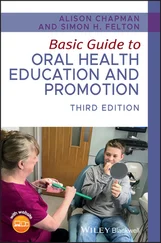

Algorithm 3.3: Implant Displacement and Migration

Dental Implant Aspiration

Aspiration of a dental implant or implant components is one of the possible complications during implant placement. Coughing, choking, wheezing, and hoarseness, chest pain, and shortness of breath are the signs and symptoms of respiratory distress secondary to aspiration, and this represents a medical emergency. In such cases, basic life support should begin immediately, and patient monitors should be applied including noninvasive blood pressure monitoring, pulse oximetry, three‐lead electrocardiogram, end‐tidal carbon dioxide monitoring, and supplemental oxygen; endotracheal intubation could be considered to secure the airway in extreme circumstances. Some authors have described the use of simple finger sweep technique to remove the aspirated material, but only if the implant or foreign body is visible in the oral cavity, or else further displacement into the airway may result. If accidental ingestion is suspected, the Heimlich maneuver should be performed and the patient should be placed on supplemental oxygen, if necessary. If an aspirated implant or implant component can be visualized, an attempt at removal can be made with the use of Magill forceps and laryngoscope. If there is a decline in oxygen saturation, endotracheal intubation or emergent surgical cricothyroidotomy may be indicated [29]. In most cases of aspiration, the foreign body (dental implant) becomes lodged in the right mainstem bronchus due to the more vertical course from the trachea, as well as its greater diameter compared to the left mainstem bronchus. A chest X‐ray must be obtained to confirm the location of an aspirated object, and this will likely include a visit to the Emergency Department. Once confirmed that the implant has been aspirated, appropriate consultations should occur with respiratory therapy or pulmonology and bronchoscopy should be carried out urgently to retrieve the implant.

Ingestion of a dental implant or implant component can pose several concerns. Due to their small size, implants and components are smaller than coins, and usually do not become lodged in the esophagus; most often, they are found in the stomach on radiographs and then move on through the digestive tract without incident; most of the time (90%), the ingested foreign object passes through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract without complications, and they also rarely become lodged at the ileocecal valve. About 10% of the time, an endoscopic retrieval may be required if the implant does not move completely through the GI tract spontaneously. Although most data show that small and blunt objects pass through the GI tract uneventfully, it is estimated that in 1% of cases a GI surgical procedure is required to retrieve an ingested object [29]. A conservative approach to this complication should include a clinical abdominal examination, obtaining abdominal X‐rays, and timely stool inspection for documentation that the implant has passed. Perforation within the GI tract is rare, but more likely to occur with sharp foreign objects, and this warrants a referral to a gastroenterologist for an early open or endoscopic assessment of the GI tract and removal of the object. Surgical intervention is recommended if the object has not passed spontaneously, has been present for >2 weeks, or if the patient becomes symptomatic with abdominal pain or rebound tenderness, guarding, nausea, or vomiting [29]. Such cases require a prompt referral to a gastroenterologist for diagnosis and management.

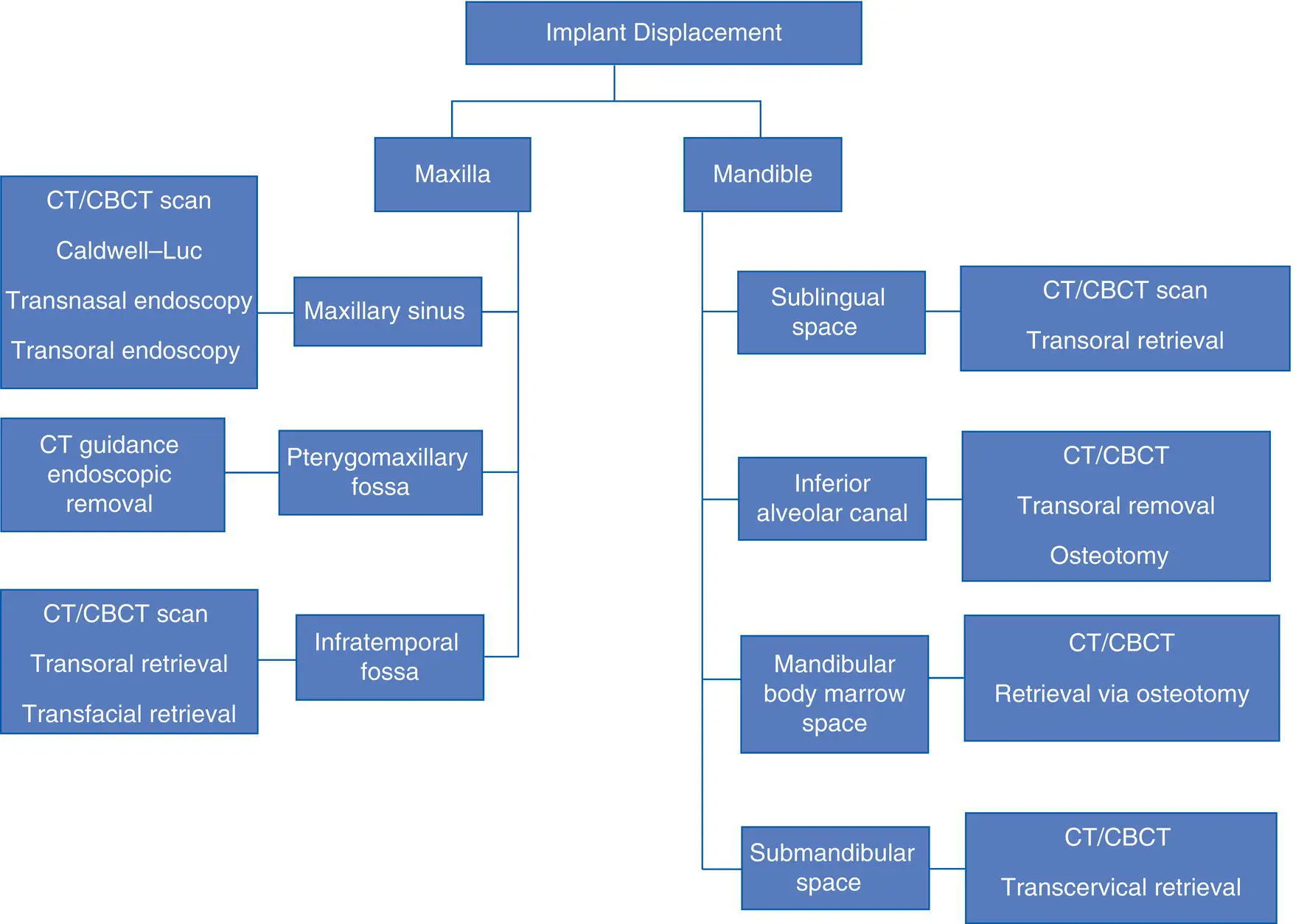

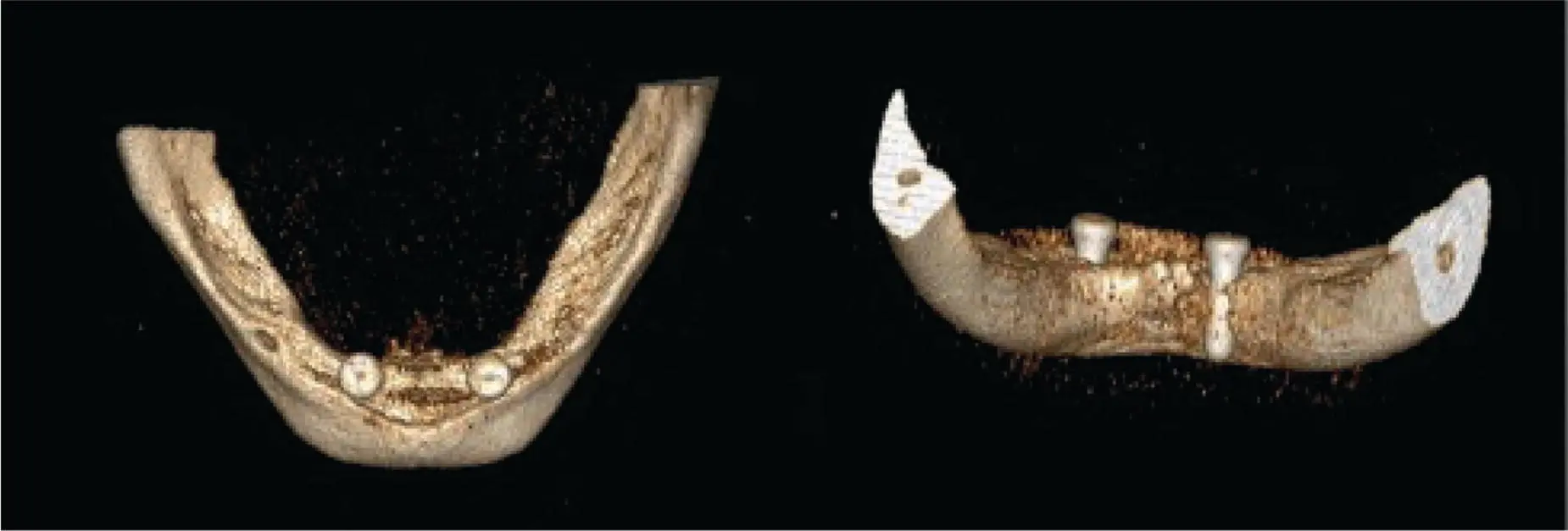

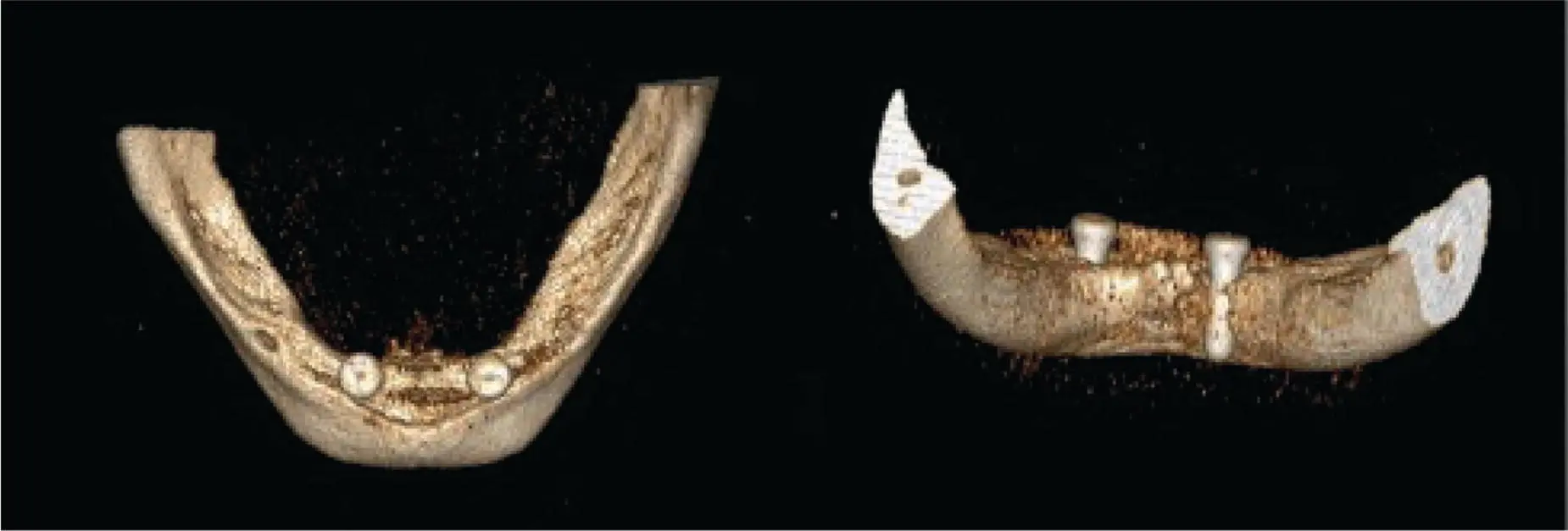

Major bleeding during dental implant placement is a rare complication, but can occur and may be life‐threatening. Failure to acknowledge the anatomical vascular variations in the maxilla and mandible can lead to iatrogenic vascular injury and major hemorrhage during implant placement. Many publications have reported that life‐threatening hemorrhage occurred most commonly when implants were placed in the anterior region of the mandible. Most patients experienced some degree of airway compromise necessitating intubation or the creation of a surgical airway ( Figure 3.10). The bleeding is believed to be caused by lingual plate violation with the drill or implant with vascular injury to the terminal branches of the sublingual or submental artery ( Figures 3.11and 3.12) [30]. There may be tributaries of the terminal branches of the sublingual or submental arteries that enter the lingual aspect of the mandible through accessory lingual foramina in the lingual cortical bone ( Figure 3.13). Also, there may be an arterial anastomosis between the sublingual and submental arteries that occurs 10% of the time. In a systematic review [30], all patients who suffered massive bleeding had received implants ≥15 mm in length. Another contributing factor to an increased frequency of bleeding is a significantly elevated systolic blood pressure at the time of vascular injury and hematoma formation leading to expansion of the hematoma. Treatment includes airway management and control of the hemorrhage, and an evaluation in an emergency department with probable, hospital admission. Basic measures to control bleeding such as immediate application of pressure on the site of suspected vascular injury, as well as blood pressure control, should be performed. Administering a local anesthetic solution with a vasoconstrictor can be useful as well. It has been suggested that arterial ligation may be technically difficult due to the engorgement of the tissues and the retraction of the offending vessel into the deeper tissues of the floor of the mouth, and should only be performed in cases of uncontrollable bleeding with no other available acute treatment options. If surgical intervention is deemed necessary, an extraoral approach for arterial ligation is preferred, but angiography with embolization remains the mainstay of therapy in a hospital imaging center ( Algorithm 3.4). Medical management should involve the use of systemic antibiotics to prevent infection of the hematoma, and corticosteroids can help to reduce swelling and limit further airway compromise.

Fig. 3.10. Floor of mouth hematoma following anterior mandible implant placement.

Fig. 3.11. Implant violation of the lingual plate that may transect the sublingual or submental vessels leading to floor of mouth hemorrhage.

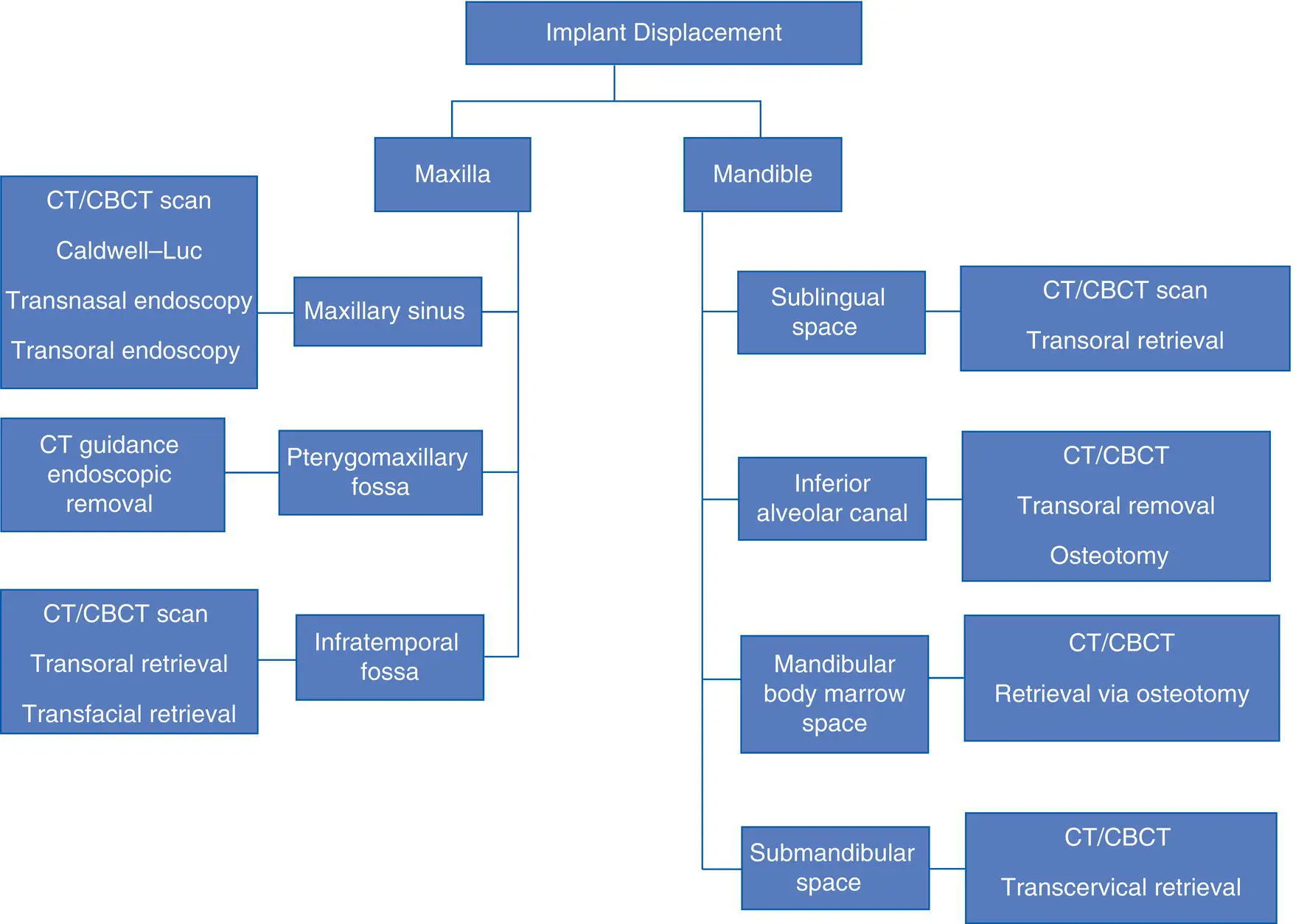

Fig. 3.12. CBCT view showing the violation of the lingual cortex by an implant.

Fig. 3.13. Lingual nutrient canal in the anterior mandible that may lead to floor of mouth bleeding from implant placement.

Brisk and pulsatile arterial bleeding can also occur during a maxillary sinus grafting procedure prior to an implant placement. The maxillary sinus receives blood supply from the posterior superior alveolar, infraorbital, and posterior lateral nasal arteries, and they are at risk of being injured with rotary instruments. The intraosseous course of the posterior superior alveolar artery, known as the alveolar antral artery, may be visible during exposure of the lateral maxillary wall for sinus grafting and attempts should be made to either avoid it, if possible, or cauterize it, prior to creation of the lateral bony window. The alveolar antral artery, or the intraosseous posterior superior alveolar artery (PSA) or anastomosis of the terminal branches of the infraorbital artery and PSA, is usually located 19 mm above the maxillary alveolar crest. Due to the caliber of the blood vessels and its retraction into the osseous canal, tamponade with gauze pressure may not be entirely effective. Bone wax may not adhere due to constant bleeding, and burnishing of the bone may not be possible. Therefore, use of hemostatic agents such as a topical thrombin sponge (or gelatin sponge [gelfoam]) or microfibrillar collagen (Avitene) should be considered [31] ( Algorithm 3.4).

Читать дальше