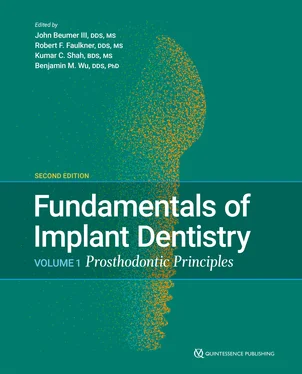

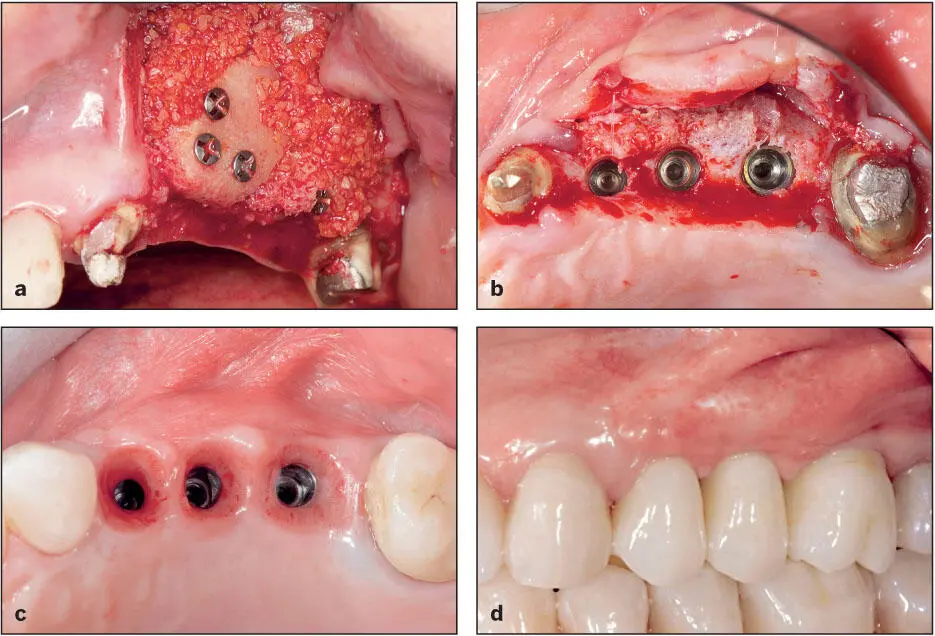

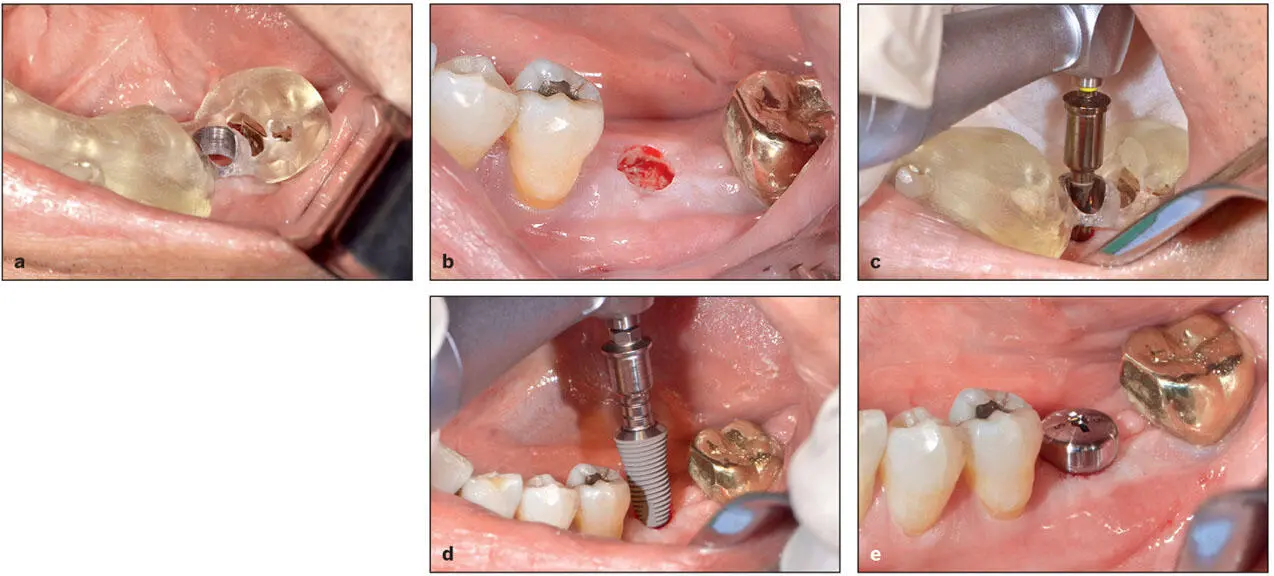

Fig 1-15 (a) Grafting defects lacking width has been predictable, and a number of different techniques have evolved (see Moy et al 3). (b and c) The zone of attached keratinized mucosa around the implants can also be increased predictably. (d) Definitive prosthesis. (Courtesy of Dr A. Pozzi.)

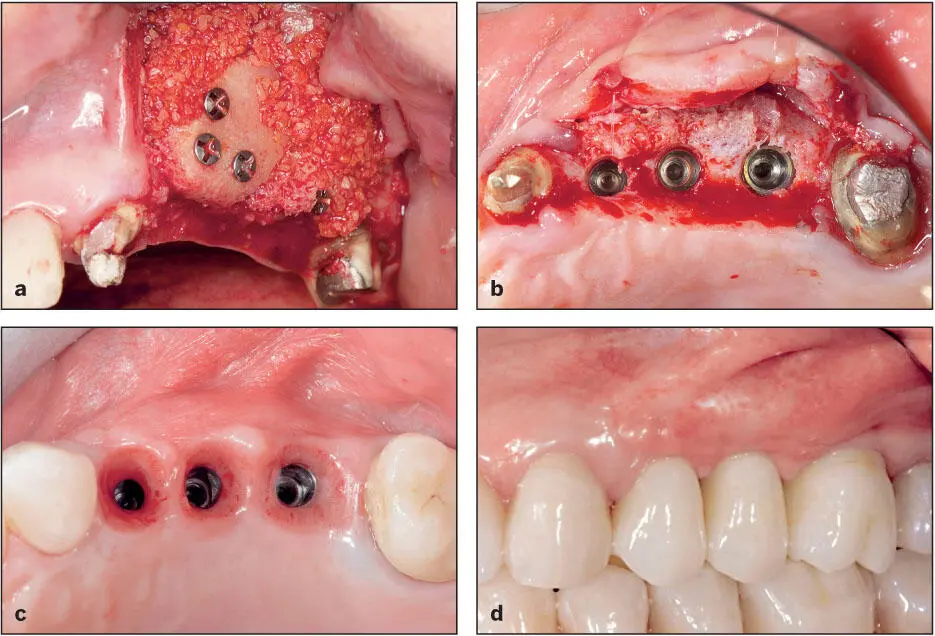

Fig 1-16 Fully guided implant surgery enables flapless surgery in select patients with ample bone and keratinized attached tissue volume. (a) The tooth-borne fully guided surgical template in position. (b) A circular patch of tissue was removed from the implant site with a tissue punch before the osteotomy site was prepared. (c) The osteotomy site is prepared. (d) The implant is inserted. (e) A healing abutment has been secured to the implant.

Implant manufacturers are increasingly introducing shorter and narrower-diameter implants with the promise of reducing the need for bone grafting. Despite short-term data, there is a lack of clinical evidence that these implants will enjoy the same long-term success as traditional-sized implants in properly grafted sites.

Impact of tilted implants

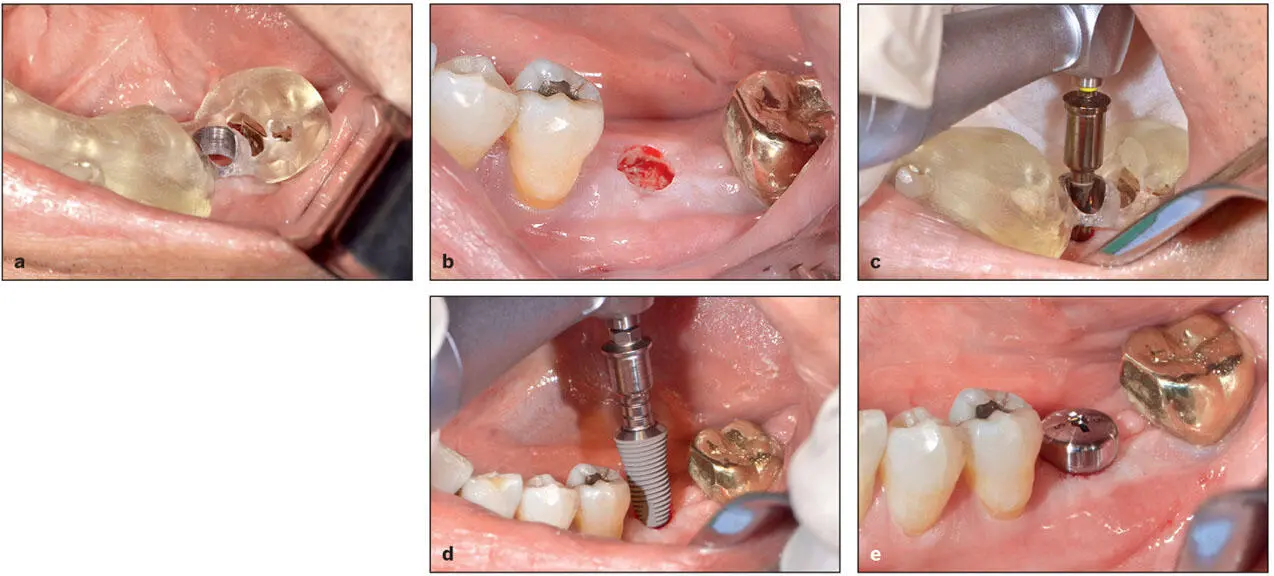

The use of tilted implants has emerged as a viable alternative to sinus augmentation, 45– 48especially in edentulous patients ( Fig 1-17). This improves the biomechanical configuration in edentulous patients (see chapters 7and 8) and recently has also been employed to restore extended edentulous areas in the posterior maxilla of partially edentulous patients ( Fig 1-18). When this concept was first introduced, the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus was exposed in order to precisely postion and angle the implant. However, with the recent improvement in the precision of fully guided implant surgery, the use of tilted implants has become a less invasive and more attractive alternative. Tilted implants can also be used for immediate loading when cross-arch stabilization is possible. The use of this design concept will be discussed in several chapters.

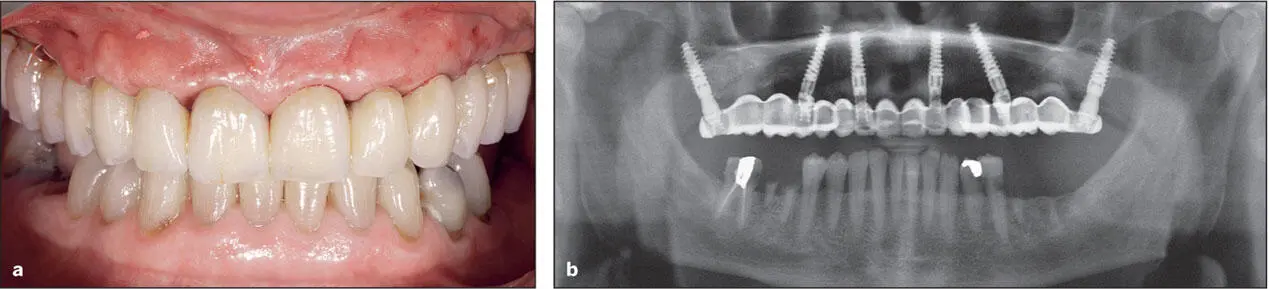

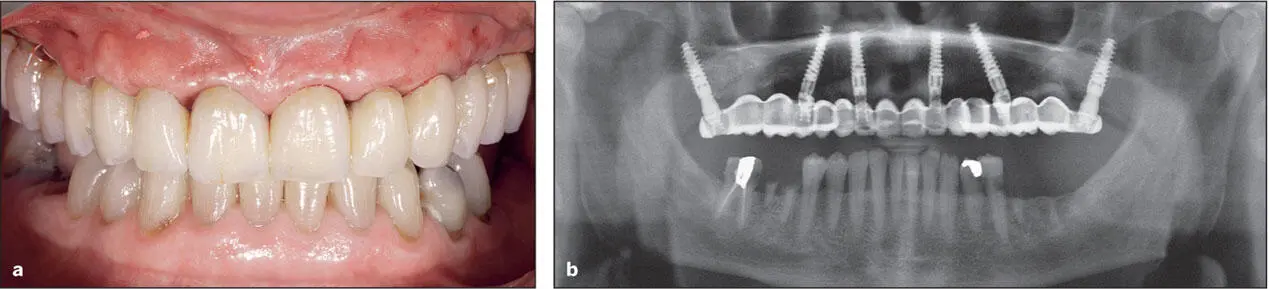

Fig 1-17 (a and b) Tilted implants have been placed to support this immediate load prosthesis. (Courtesy of Dr A. Pozzi.)

Fig 1-18 (a and b) Tilted implants have been used to restore an extended edentulous area in the posterior maxilla. (Courtesy of Dr A. Pozzi.)

Impact of Loading Protocols

The original treatment protocols for using machined-surface implants required several months’ delay after implant placement before the prosthesis could be delivered and placed into function. Most patients were required to use removable prostheses during this period. During the last several years, various immediate and early loading protocols have been proposed as implant macro shapes and implant surface textures have evolved (see Fig 1-17). Recent advances in CAD/CAM technologies have provided an additional stimulus to this trend. In this new edition, we offer guidelines regarding the various loading protocols currently in use, namely immediate loading, immediate provisionalization, early loading, and delayed (conventional) loading. The reader should understand that the immediate load prosthesis is a complex, technically demanding treatment and should be attempted only after the implant team has acquired the necessary experience. Mistakes in clinical judgment and execution can lead to a higher incidence of implant failure and loss of the prosthesis.

Impact of new prosthodontic materials

Several new materials and combinations of materials have been introduced to meet the unique demands placed upon implant-supported prostheses. Unfortunately, many materials used for tooth-supported prostheses have proven to be unsuitable for implant-supported prostheses. For example, the crazing and fracture of the resin-bonded systems used to restore extended edentulous areas with implant-supported fixed dental prostheses in the posterior quadrants was quite disappointing. In this edition, we have added an additional chapter ( chapter 4) devoted to materials and, where possible, we provide the reader with evidence-based guidelines regarding selection of the appropriate materials for any given application.

Impact of digital technologies upon the role of the restorative dentist

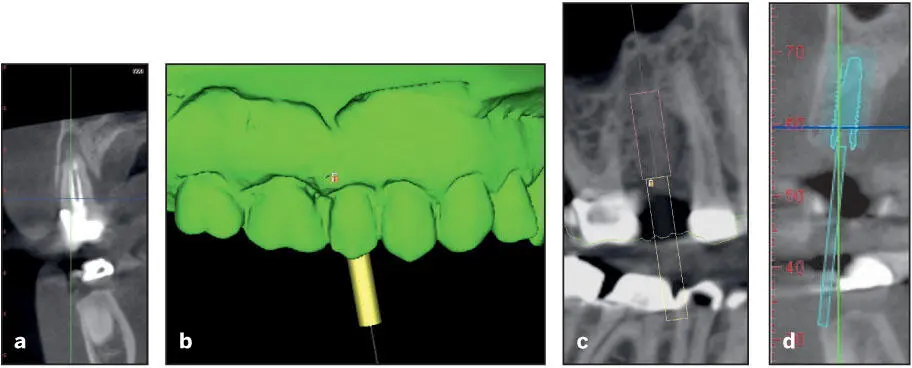

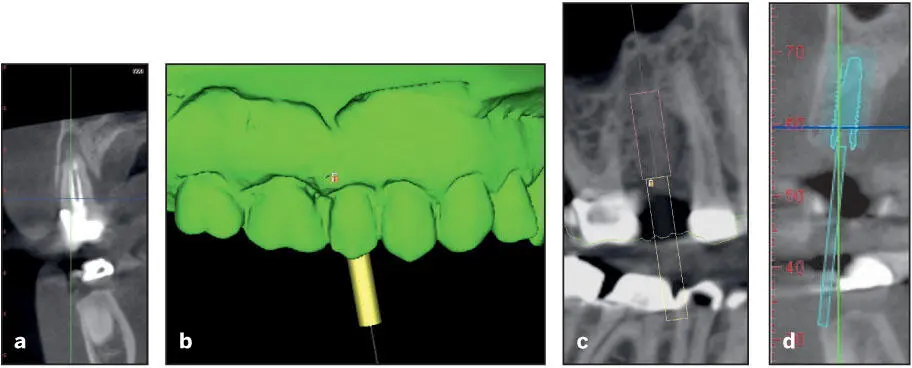

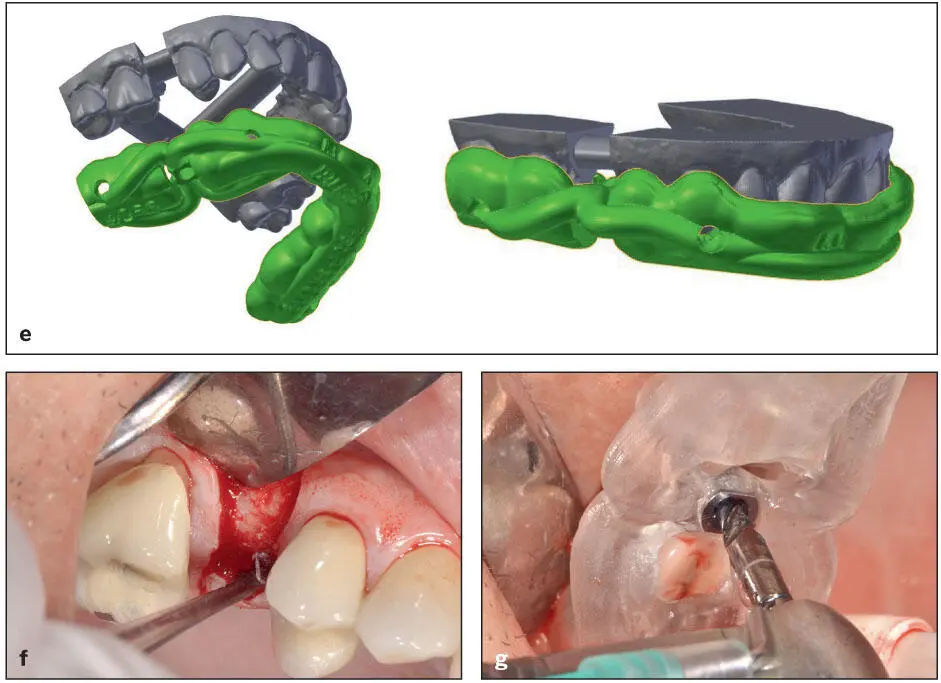

As mentioned previously, digital technologies have had a dramatic impact upon the means of implant site evaluation and implant surgery. These new technologies—CBCT scans and the associated software for guided surgery, navigation systems, and 3D jaw movement recording and analysis systems (electronic pantograph)—allow prosthodontists and restorative dentists to virtually analyze the 3D characteristics of the potential implant bone site and design and fabricate accurate surgical drill guides ( Fig 1-19). These new technologies also help prosthodontists and restorative dentists to better determine which patients are best served by referral to a periodontist or oral surgeon for implant placement as opposed to placing the implants themselves.

Fig 1-19 (a) The maxillary second premolar is to be extracted due to an endodontic failure. (b to d) CBCT scans are obtained, and the position, angulation, and size of the implant are selected. (e) The appropriate software permits the design and fabrication of a surgical template. (f) A fl ap is refl ected. (g) The surgical drill guide is positioned, and the osteotomy site is prepared.

Follow-up data analysis

In recent years, clinical study design has improved, and as a result, clinical decisions have become increasingly evidence based. However, still far too many studies rely on short follow-up times when assessing outcomes. Many current studies report data with only 1 or 2 years of follow-up data, which in most instances is quite insufficient. Even the traditional 5-year follow-up period may not enable clinicians to make truly evidence-based choices, especially when attempting to determine whether bone and soft tissue levels ever become stable. Even when implant treatment is executed properly and under ideal conditions, phenomena such as mesial migration and continued eruption of adjacent natural dentition and apical migration of bone and peri-implant soft tissues may render the outcome suboptimal. These phenomena are rarely recognized at 5-year follow-up and therefore have been largely ignored in the implant literature and by those presenting continuing education programs of instruction. However, these phenomena are often seen after 5 or more years of follow-up ( Figs 1-20and 1-21), and given their frequency, patients must be informed that it is likely that their implant-retained restoration may need to be remade at some future date. In addition, it is the clinician’s responsibility to be aware of and plan for these eventualities and design prostheses that will mitigate their effects.

Читать дальше