The development of shock is due to a dysregulated systemic inflammatory and immune response to microbial invasion that results in vasodilatation, hypotension and organ dysfunction. Septic patients have a metabolic acidosis with a raised lactate, detectable on sampling of arterial or venous blood.

In trauma patients, sepsis is unlikely to cause shock at presentation. It is most likely to develop later in patients with penetrating abdominal injuries and in whom the peritoneal cavity has been contaminated by intestinal contents.

The key to management is a high degree of suspicion, rapid diagnosis and urgent treatment, as perinatal sepsis is a rapidly progressive disease. Pregnant women with septic shock will require early referral to critical care. See Chapter 7for further information on maternal septic shock.

Cardiogenic shock in pregnancy is a life‐threatening condition due to failure of the ventricles to produce an adequate cardiac output. Ischaemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy and pulmonary and amniotic fluid embolism are the main causes of cardiogenic shock in pregnancy.

In trauma, patients can develop cardiogenic shock due to penetrating injury, cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax and myocardial contusion.

There is a significant overlap in the signs and symptoms between these forms of shock and hypovolaemic shock. One distinguishing feature is the extreme air hunger and orthopnoea seen in patients suffering cardiogenic shock. Listening to the chest may give clues of congestion due to increased pressure in the pulmonary circulation causing pulmonary oedema.

Cardiogenic shock has a high mortality and mandates multidisciplinary consultant management with involvement from cardiology, cardiac surgery and critical care. Transfer to a centre able to offer complex invasive cardiac support may be required.

The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds and should be considered if the patient develops:

Unexplained hypotension or bronchospasm

Unexplained tachycardia or bradycardia

Angioedema (often absent in severe cases)

Unexplained cardiac arrest where other causes are excluded

Cutaneous flushing in association with one or more of the above signs (often absent in severe cases)

Box 6.1Management of anaphylactic shock

Stop administration of drug(s)/blood product likely to have caused anaphylaxis

Resuscitation as for any collapse following ABC principles with reassessment

The key treatment therapies are oxygen, adrenaline and fluids. Adrenaline is very effective and should be given as early as possible

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be considered when systolic blood pressure is <50 mmHg or the patient is in cardiac arrest

Source : Adapted from AAGBI (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland). Quick Reference Handbook 3‐1 Anaphylaxis , 2019

Treatment of anaphylactic shock ( Box 6.1) is as follows:

1 Call for help and note the time.

2 Call for cardiac arrest trolley, anaphylaxis treatment and investigation pack (should be in theatre recovery – familiarise where it is kept in your unit).

3 Remove all potential causative agents.

4 Manual uterine displacement.

5 Open and maintain airway. Give high‐flow/100% oxygen and ensure adequate ventilation. Intubation may be required for severe stridor or cardiorespiratory collapse.

6 Elevate the legs if there is hypotension.

7 If systolic blood pressure is <50 mmHg or there is cardiac arrest start CPR.

8 Give drugs to treat hypotension:Adrenaline 0.5 mg (0.5 ml of 1:1000) intramuscularly every 5 minutes until there is improvement in the pulse and blood pressure. Intravenous adrenaline may be used by experienced (anaesthetic) staff in a monitored patient in 50 microgram boluses (0.5 ml of 1:10 000) titrated against response.If intravenous access proves difficult obtain intraosseous access. Hypotension may be resistant and require prolonged treatment.Consider starting an adrenaline infusion after three boluses: 5 mg in 500 ml dextrose (1:100 000) titrated to effect, or 3 mg in 50 ml 0.9% saline started at 3 ml/h (= 3 micrograms/min) titrated to maximum of 40 ml/h (40 micrograms/min).Glucagon 1 mg repeated as necessary in beta‐blocked patient unresponsive to adrenaline.If hypotension resistant give alternate vasopressor: metaraminol, noradrenaline or vasopressin.

9 Intravascular volume expansion with crystalloid 20 ml/kg: initial bolus repeated until hypotension is resolved.

10 Other drugs that can be given:Hydrocortisone 200 mg intravenously.Chlorphenamine 10 mg intravenously.

11 If there is persistent bronchospasm despite an adequate dose of adrenaline to stabilise the blood pressure, consider bronchodilators, e.g.:Salbutamol 5 mg via oxygen‐driven nebuliser, or 250 micrograms diluted intravenous slow bolus.Magnesium sulphate 2 g intravenously over 20 minutes.Aminophylline 5 mg/kg intravenously over 20 minutes if not already taking theophylline.

12 Check fetal heart and continuously monitor by cardiotocography. If in cardiac arrest, perform perimortem section. If not in cardiac arrest, consider timing and method of delivery once maternal status is stabilised.

13 Take a 5–10 ml clotted blood sample for serum tryptase as soon as the patient is stable. Plan for repeat sample at 1–2 hours and >24 hours.

14 Plan to insert arterial and central venous pressure lines and transfer the patient to a critical care area.

15 Prevent readministration of possible trigger agents (allergy band, update notes and drug chart, liaise with anaphylaxis lead regarding ongoing investigation and referral ( www.bsaci.org) to identify causative agent). Inform the patient, obstetric consultant and GP and report to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA, www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard).

Hypovolaemia is the most common cause of shock in obstetric and trauma patients

A high index of suspicion is essential during assessment to ensure early recognition and prompt resuscitation

In haemorrhagic shock, management requires replacement of lost volume and oxygen carrying capacity, prevention of coagulopathy and immediate control of haemorrhage either by direct compression, splintage or, where necessary, by urgent surgery

Other forms of shock require equal vigilance and early resuscitative measures to restore circulation and tissue perfusion

1 Kemp HI, Cook TM, Harper NJN. UK anaesthetists’ perspectives and experiences of severe perioperative anaphylaxis. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119: 132–9. (Gives details of the Sixth National Audit Project (NAP6).)

2 NAP (National Audit Projects). https://www.nationalauditprojects.org.uk/NAP6home(last accessed January 2022). (Gives resources for the management, investigation and communication required following life‐threatening anaphylaxis.)

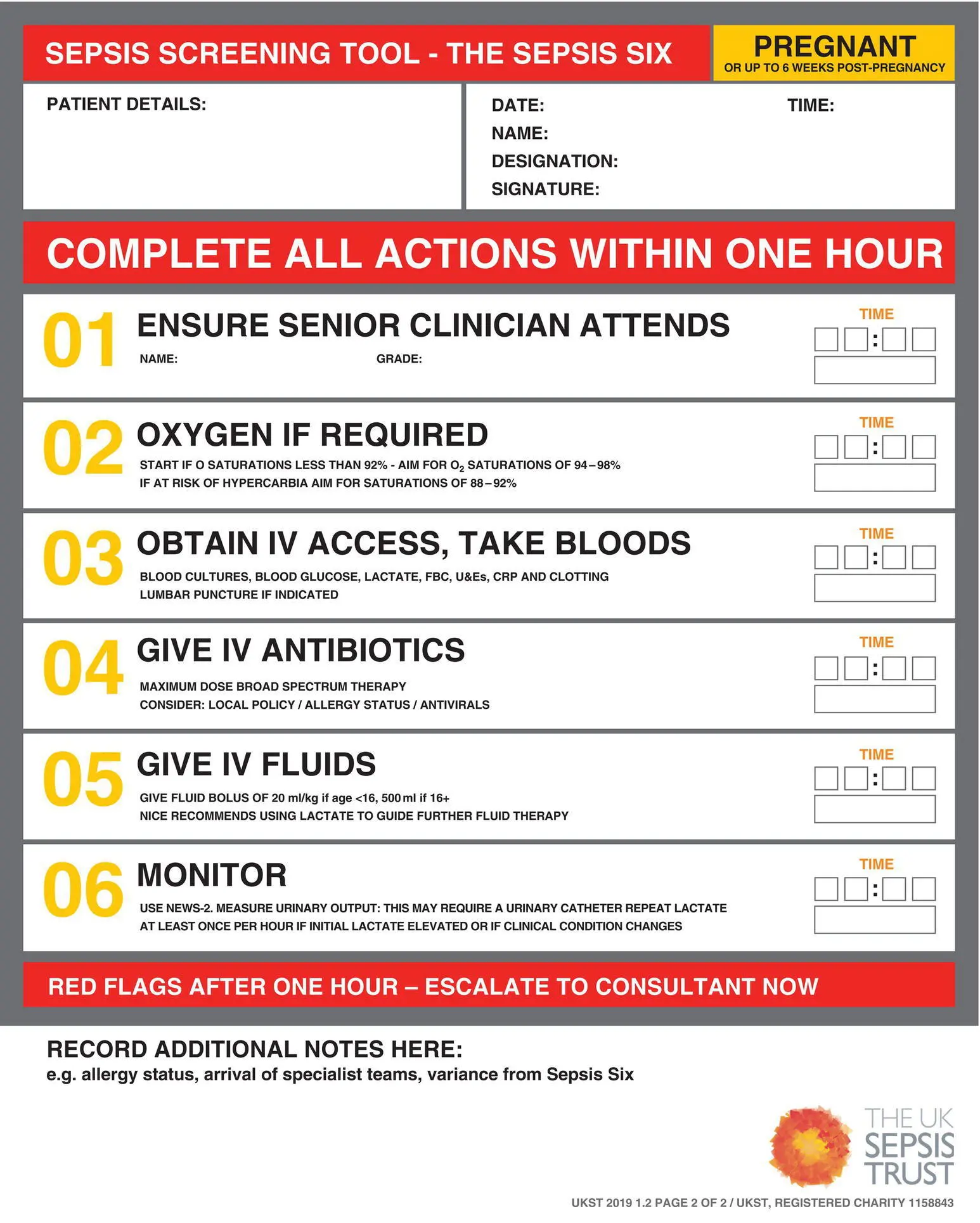

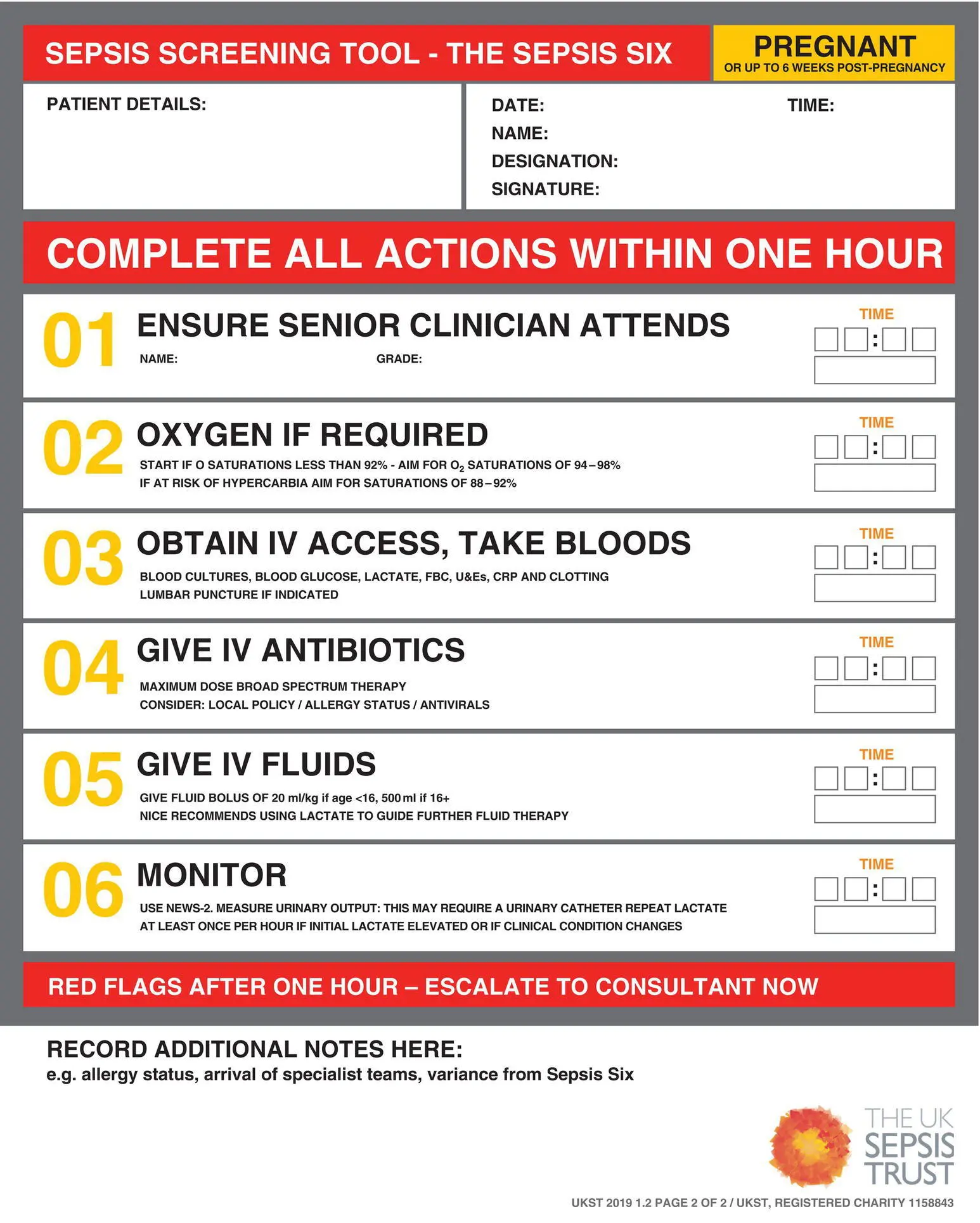

Algorithm 7.1 The Sepsis Six

Source : Nutbeam T, Daniels R on behalf of the UK Sepsis Trust. © 2019 UK Sepsis Trust

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Recognise the septic woman

Commence emergency management

Arrange appropriate investigations and referral

7.1 Introduction and definition

Worldwide sepsis causes 1 in 10 maternal deaths and is the third commonest cause of direct maternal death (Turner, 2019). To reduce avoidable deaths, women with sepsis need to be recognised so that treatment can be initiated early .

Читать дальше