If we are aware that an error is more likely we can be more proactive in detecting them. Alongside distractions, two common situations that make errors more likely are stress and fatigue. Stress is not only a source of error when we are overworked and overstimulated, but also, at the other end of the spectrum, when we are understimulated we become inattentive.

The acronym HALThas been used to describe situations when error is more likely:

| H |

Hungry |

| A |

Angry |

| L |

Late |

| T |

Tired |

Consider how many times in the last week you have been hungry, angry, late or tired and still worked in a setting where errors could have had significant implications. Unfortunately, in many work cultures these emotional and/or physical states are seen as inevitable.

I’M SAFEhas been used as a checklist in the aviation industry, asking whether the individual may be affected by:

| I |

Illness |

| M |

Medication |

| S |

Stress |

| A |

Alcohol |

| F |

Fatigue |

| E |

Eating |

Ideally, individuals who are potentially compromised need to be supported appropriately, allowed time to recover and the team made aware. How this can be achieved in the middle of a night shift can be problematic.

Humans are prone to several ‘cognitive biases’ (examples include normalcy, confirmation, conformity and fixation biases). Normalcy bias is the tendency to underestimate both the seriousness of a situation and the likelihood of a poor outcome – i.e. you rule out the worst‐case scenario.

Confirmation bias is also common and is the tendency to only pay attention to information that fits in with your own ‘mental model’ of the situation in hand. There is a reluctance to change one’s mind even in the presence of contradictory evidence. When this occurs, people favour information that confirms their preconceptions or hypotheses regardless of whether the information is true. This may be observed within the healthcare setting during the process of a referral or handover. An example of this might be a clinician receiving a phone call requesting them to attend the ward to review an acutely deteriorating postnatal woman. The clinician is advised that the woman has collapsed. On their way to the ward the clinician builds up a series of preconceived expectations around what they will find upon their arrival. They may even formulate a management plan whilst travelling to the scene, based upon their expectations. Once this ‘mindset’ is established it can be difficult to shift. On arrival, the clinician examines the systems affected by the presumed diagnosis. They seek to confirm their expectation of collapse due to PPH by focusing on palpating the uterine fundus at the expense of a thorough systematic assessment. They do not pick up the fact that the woman is having difficulty breathing and their preconceived ideas that this is due to PPH mean that the remainder of the assessment is completed without due attention and more as a rehearsed exercise rather than an open‐minded exploration. In this case the eventual diagnosis was pulmonary embolism which was a very late consideration in the diagnostic pathway.

Apart from thorough history and clinical assessment, using the expertise within your team by carefully listening to alternative views or challenges can minimise the effects of these cognitive biases.

Cognitive aids: checklists, guidelines and protocols

Cognitive aids such as guidelines or checklists are important because the human memory is not infallible. They also confer team understanding through the use of a standardised response. This reduces stress. This is especially true where an uncommon emergency event occurs. The team may be unfamiliar with one another and each member will be trying to remember what to do, what treatments are required and in what order. A good team leader will use the available cognitive aids as a prompt and the team’s members can use it as a resource so that they can plan ahead. Safe practice is promoted through the use of these tools in an emergency rather than relying on memory.

Trainees in all disciplines are often reluctant to call for senior help, partly due to not recognising the severity of the situation and partly due to concerns about wasting the time of seniors. With all emergency events, and in particular with obstetric emergencies, escalation and appropriate help should be summoned as soon as possible. Remember, help will not arrive instantly.

Using all available resources

Team resources include staff, observations, equipment, cognitive aids and the facilities in the local area. It is the team leader’s role to continually consider the appropriateness of utilising available, untasked staff or equipment to optimise the patient’s care and prevent a bottleneck in the treatment pathway.

Wherever possible it helps to have a facilitated debrief following an adverse clinical event. It is best if the debrief is viewed as a normal part of the process of dealing with all obstetric emergencies rather than being reserved for catastrophic events. The aim of a debrief is to summarise any particular issues or problems that the team had, and reflect on how the team performed. Some organisations have set templates to facilitate this. It gives the opportunity for individuals, teams and organisations to continually develop.

Whilst a ‘hot’ debrief immediately after the event may be useful in certain situations, it is not always ideal. Some situations in obstetrics can be emotionally draining, especially when maternal or neonatal outcome is poor. A balance must be established whereby formal debrief and feedback to all involved team members occurs within a reasonably short timeframe. All team members must be aware of looking out for the emotional needs of colleagues who may have been particularly emotionally traumatised during an emergency situation.

In this chapter we have given a brief introduction to human factors and described how lack of awareness about the importance of communication, situation awareness, leadership, team working and decision making can lead to patient harm and adverse events. It is really important for you to use every opportunity to reflect on and develop your own performance and influence the development of others and the team. Appropriate debriefing is included in the scenarios for the mMOET course, which may be used to help you to incorporate this process into your own clinical practice.

1 Bromiley M. Just a Routine Operation. https://vimeo.com/970665. Clinical Human Factors Group, www.chfg.co.uk (last accessed February 2022).

2 Flin R, O’Connor P, Crichton M. Safety at the Sharp End: A Guide to Non‐technical Skills. Abingdon: CRC Press, 2008.

PART 2 Recognition

CHAPTER 5 Recognising the seriously sick patient

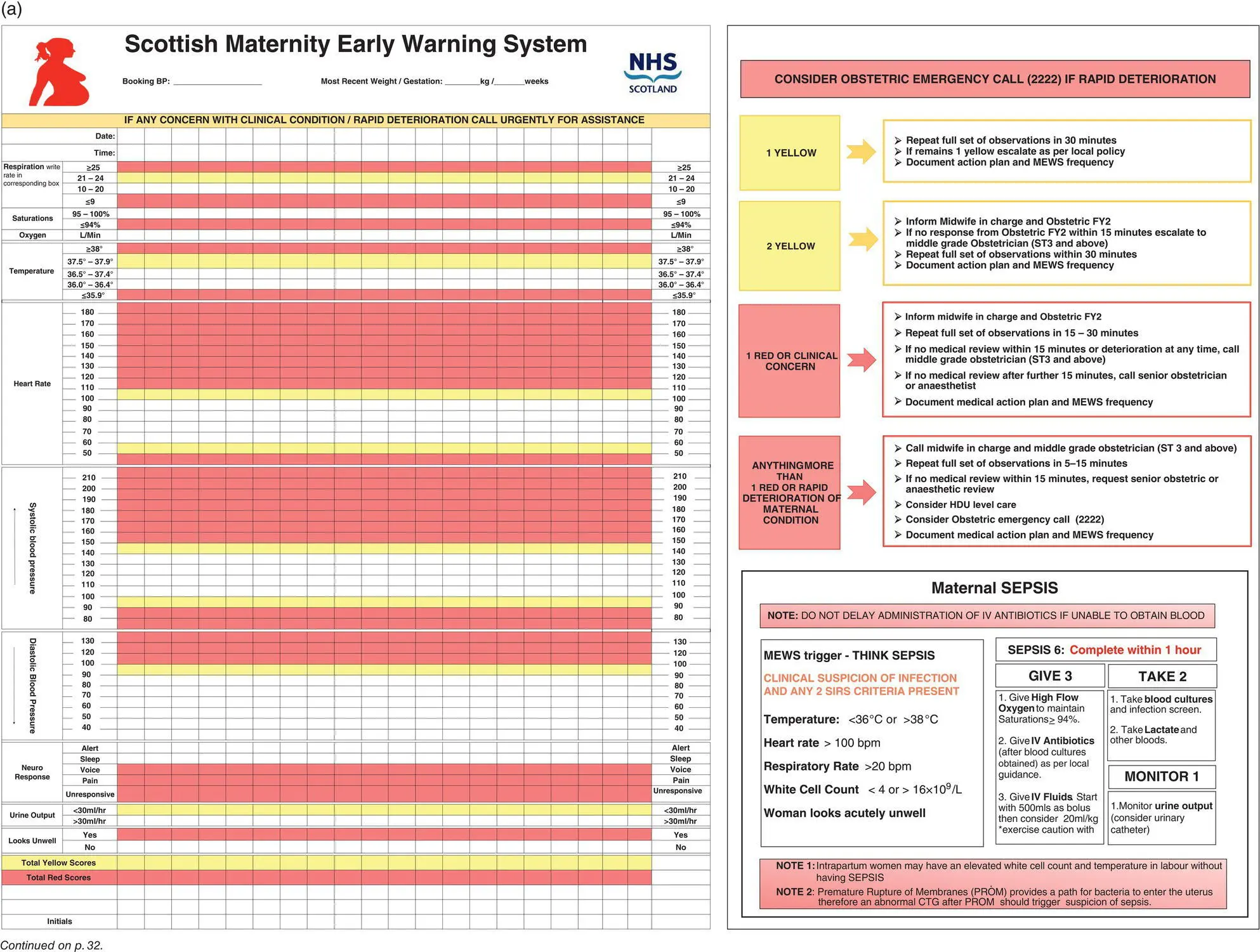

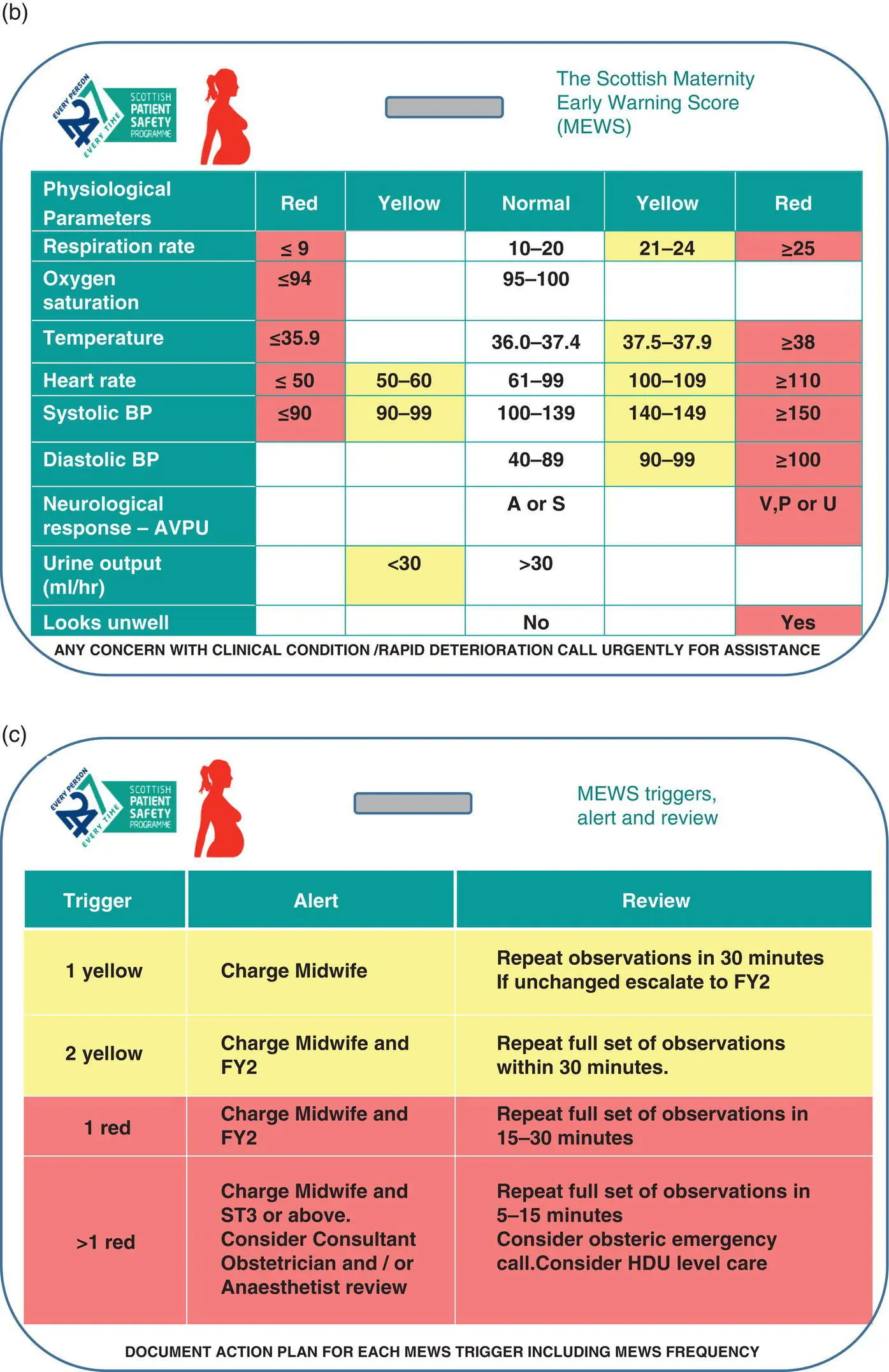

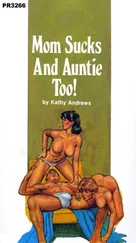

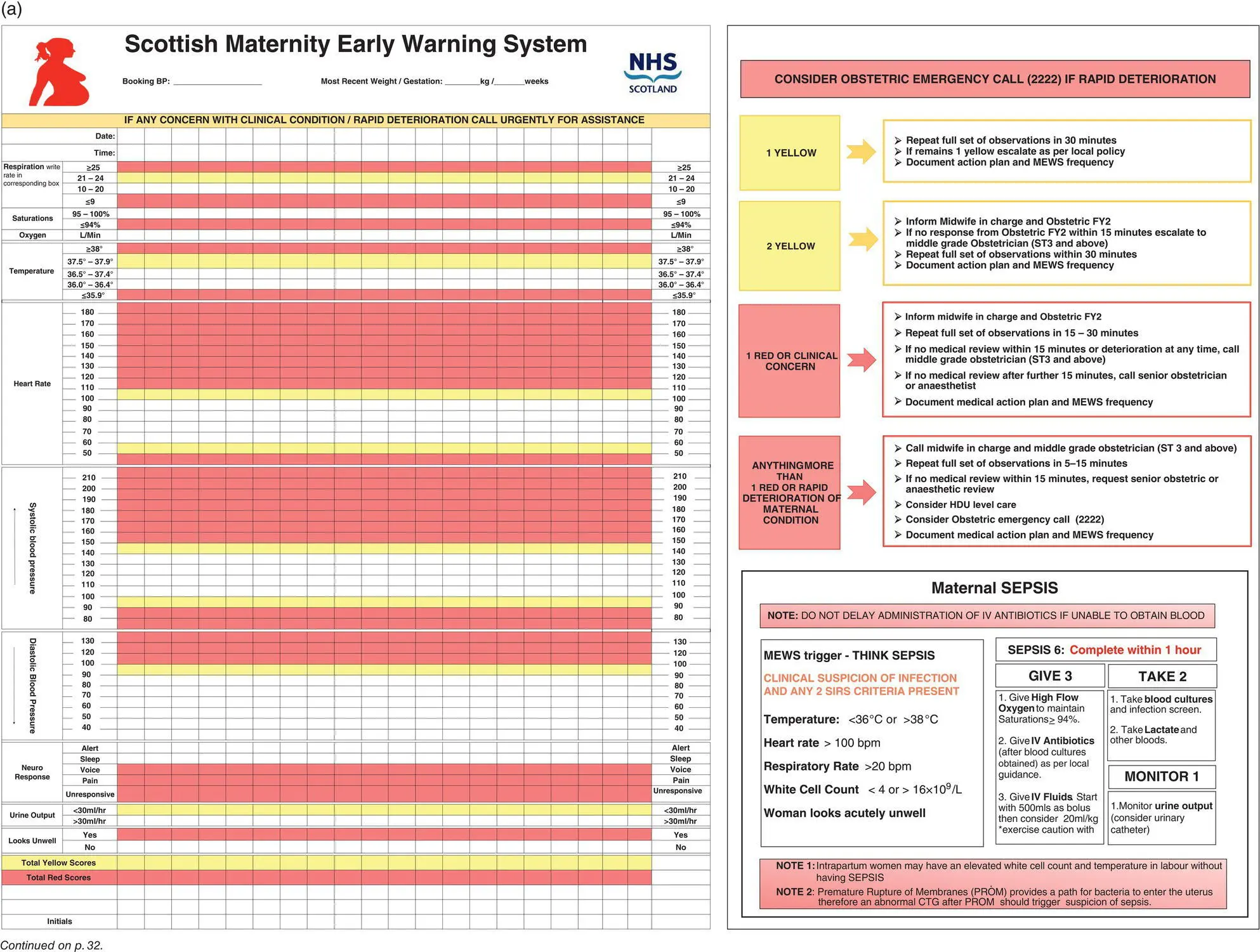

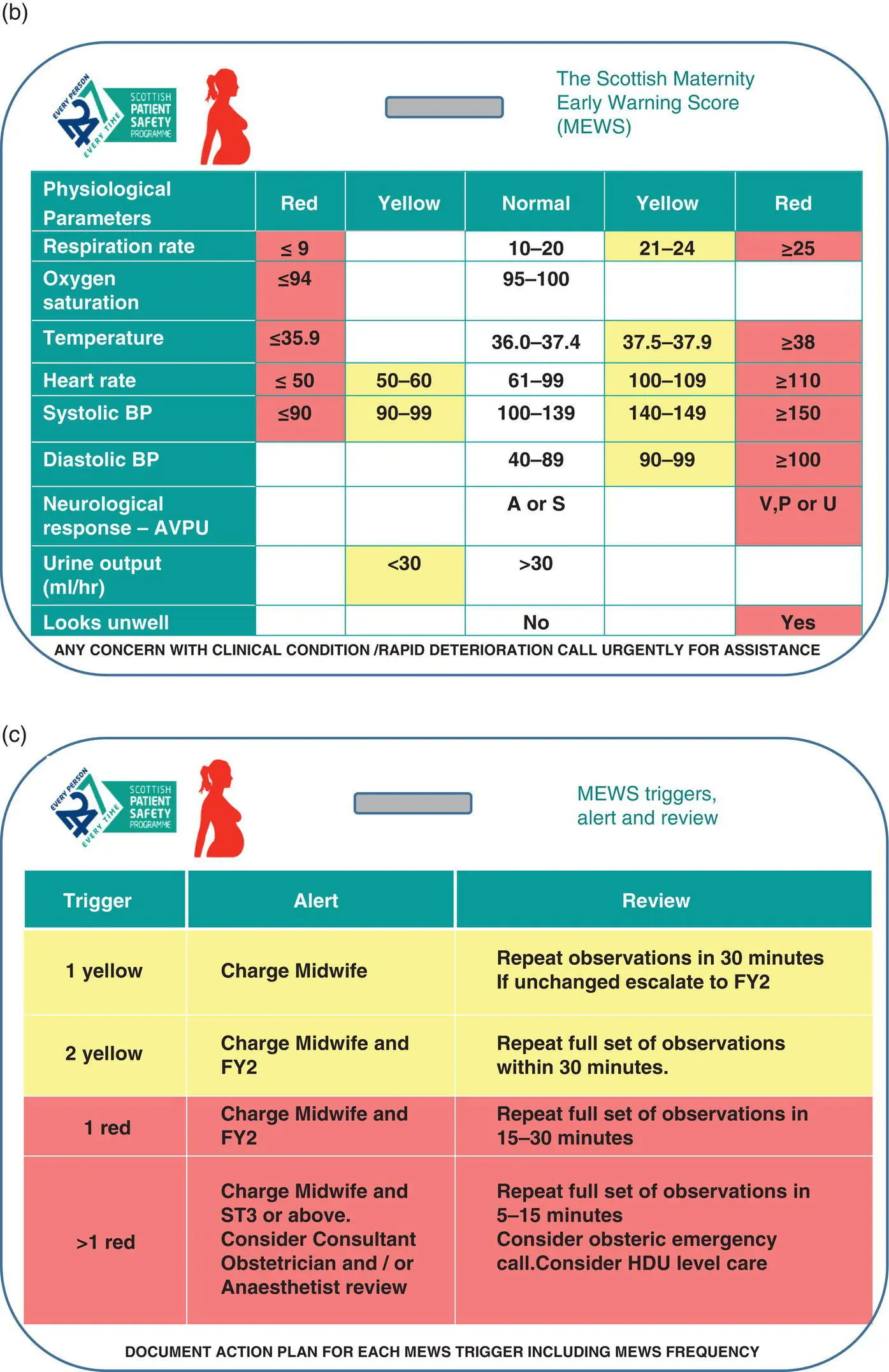

Algorithm 5.1 Scottish national MEWS chart: (a) front of MEWS chart

Читать дальше