Probe – this is used where a person notices something they think might be a problem. They verbalise the issue, often as a question. ‘Have you noticed that this woman is bleeding excessively?’

Alert – the observer strengthens and directs their statement and suggests a course of action. ‘Dr Brown, I am concerned, the mother is still bleeding more than I’d expect – shall I give ergometrine?’

Challenge – the situation requires urgent attention. One of the key protagonists needs to be directly engaged. If possible the speaker places him‐ or herself into the eye line of the person they wish to communicate with. ‘Dr Brown, you must listen to me now, this patient needs more action now as the bleeding is not slowing down.’

Emergency – this is used where all else has failed and/or the observer perceives a critical event is about to occur. Where possible a physical signal or physical barrier should be employed together with clear verbalisation. ‘Dr Brown, you are not acting on this woman’s significant ongoing bleeding. Please move aside and I will assess directly myself.’

The PACE structure can be commenced at any appropriate level and escalated until a satisfactory response is gained. If an adverse event is imminent then it may be relevant to start at the declaring ‘emergency’ stage, whereas a much lower level of concern may well start at a ‘probing’ question.

Some industries have also additionally adopted organisation‐wide critical phrases that convey the importance of the situation, e.g. ‘I am concerned’, ‘I am uncomfortable’ or ‘I am scared’. In an effective team where the leader actively listens to concerns raised by his/her team members, progressing beyond the ‘P’ or ‘A’ step should rarely be needed.

4.8 Situation (or situational) awareness

A key element of good team working and leadership is to be fully aware of what is happening; this is termed situation awareness. It not only involves seeing what is happening, but also captures how this is interpreted and understood, how decisions are made and ultimately involves planning ahead.

Typically, three levels of situation awareness are described:

Level 1 – What is going on? Collecting information

Level 2 – So what? Interpreting the information

Level 3 – Now what? Anticipating the future state

Level 1 – the basic level (What is going on? Collecting information)

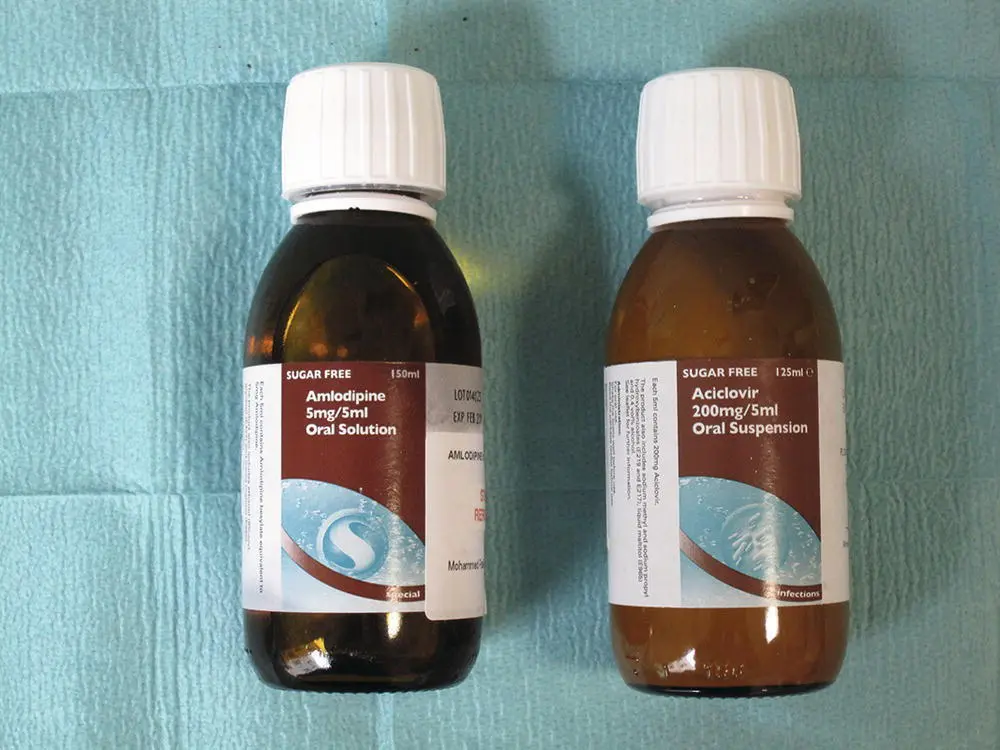

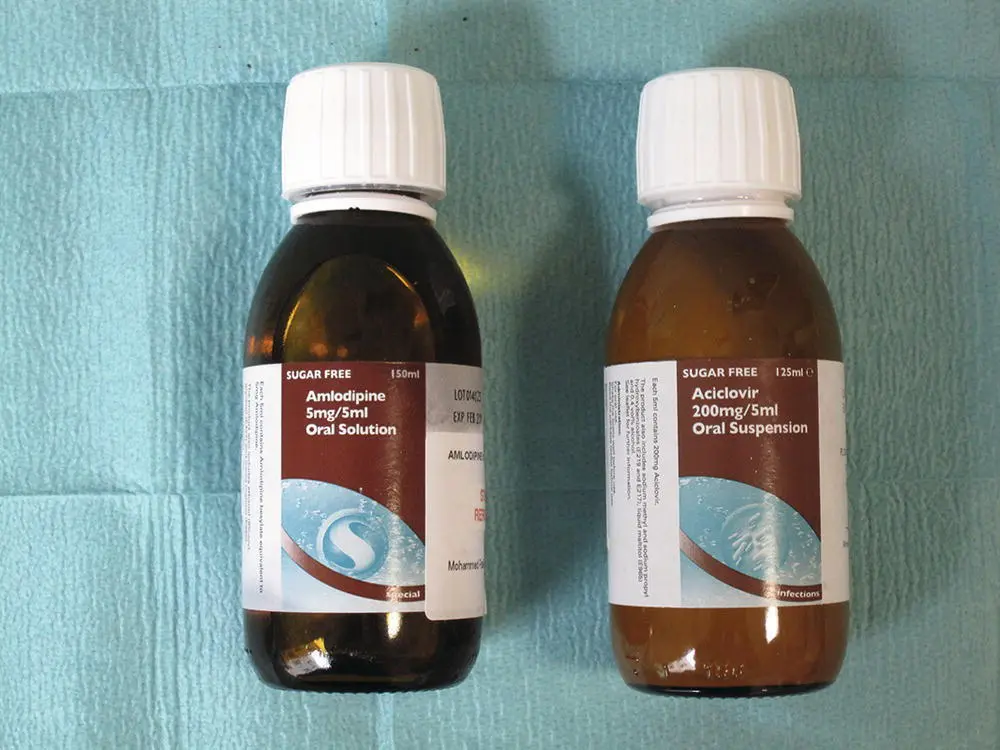

We are prone to errors even at this level: the risk is that what is seen or heard is what is expected to be seen or heard, rather than what is actually occurring. Figure 4.2shows the similar package design of two different medications, making errors more likely. It is important to really concentrate on seeing what is actually there.

Figure 4.2 Similar package design of two different medications

Within healthcare, distractions become the norm to such an extent individuals are often not even aware of them. The risk is that mistakes are made and information is missed. It is important to try to challenge interruptions when doing critical tasks, and when they do occur, restart the task from the beginning, rather than from where it is considered the interruption occurred. Some organisations are looking at specific quiet areas for critical tasks. Whatever the local set up, the key is to develop and maintain everyone’s awareness of how distraction greatly increases the chance of error.

Level 2 (So what? Interpreting the information)

This encompasses how someone’s understanding forms from what has been seen. To minimise level 2 errors consideration is needed as to how the human brain works, recognises things and makes decisions and choices. This level of detail is beyond the scope of this introductory chapter (for those who are interested in pursuing this further Safety at the Sharp End by Flin et al. (2008) is an excellent learning resource for the whole field of human factors in healthcare). Therefore this section will focus on a part of this – the decision making that leads into level 3.

On the face of it the practice of decision making is familiar to everyone. However, to understand the factors that can compromise this process it is important to understand the factors that will influence the decision made. To make a good decision a person needs to assess all aspects of a problem, identify the possible responses to the problem, consider the consequences of each of those responses and then weigh up the advantages and disadvantages in order to draw a conclusion. Having completed this, they then need to communicate their decision to their team.

Good situation awareness is a basic prerequisite of this process. To achieve this, the decision maker must ensure they have all the key information. In a well‐functioning team everyone is on the alert for ambiguities, biases or conflicting information. Any inconsistent facts should be treated as a potential marker for faulty situation awareness. It is important not to brush them off as unimportant anomalies in the absence of evidence to support such a decision.

In many clinical situations there can be a significant pressure of time. Where this is not the case then no decision‐making process should be concluded until the team is satisfied they have all the information and have considered all the options. Where time is a pressure, a certain amount of pragmatism must be employed. There is plenty of evidence to confirm that practice and experience can mitigate some of the negative effects of abbreviating a decision‐making process. Those making decisions under such circumstances need to remain aware of the short‐cuts they have taken and be ready to receive feedback from their team, particularly if any member of the team has significant concerns about the proposed course of action.

Level 3 (Now what? Anticipating the future state)

Having gathered information using all of our senses (level 1) we then need to interpret the information (level 2) before we plan forward using previous experience, seeking input from the team when required (level 3). Finally, we must decide the plan of action and communicate this to the team.

The individuals in the team may have a unique awareness of the situation depending on their previous experience, specialty, physical position, etc. The team’s situation awareness will often be greater than that of any one individual. However this can only be exploited if the individual elements are effectively communicated clearly between team members. Effective leaders actively encourage this as it results in a ‘shared mental model’, a feature associated with effective teams.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) is integrating human factors within the new UK postgraduate training curriculum and has developed learning resources within the ‘Each Baby Counts’ initiative: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines‐research‐services/audit‐quality‐improvement/each‐baby‐counts/implementation/improving‐human‐factors/(last accessed October 2020).

4.9 Improving team and individual performance

In addition to effective communication, team working, situation awareness, leadership and followership skills, there are a number of other ways that team and individual performance can be further developed and improved.

Awareness of situations when errors are more likely

Читать дальше