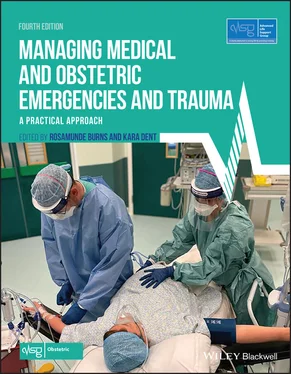

Source : Scottish patient safety programme, Maternity and Children quality Improvement programme. © The Improvement Hub

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Identify the current causes of maternal mortality and morbidity and the issues with their detection and treatment

Describe a systematic approach to monitoring using early warning charts to aid recognition of women at risk

Recognise ‘red flag’ symptoms and their need for an urgent response by the obstetric team and other specialties

Recurrent themes in mortality and morbidity reports identify that suboptimal care may have contributed to the deaths described in these reports. With more than two thirds of cases having pre‐existing co‐morbidities and indirect deaths exceeding direct, the importance of coordinated care across specialties is emphasised. Failure to recognise symptoms and signs of potentially life‐threatening conditions, delay in acting on findings and delay seeking help from appropriate specialists are all of particular concern. Attention is therefore focused on ways to improve the recognition of, and timely response to, clinical signs of the deteriorating patient.

The diagnosis of a severe life‐threatening condition in a pregnant or recently pregnant woman is challenging when the onset is insidious or atypical. This is compounded by the sick pregnant woman presenting to a non‐obstetric area such as the emergency department where staff are not familiar with pregnancy physiology. The different response to impending critical illness through vital signs can be missed in these circumstances.

Not only ‘high risk’ women become critically ill. Often it is not possible to predict if or when this might happen to any obstetric patient. The relative rarity of life‐threatening events in pregnancy reinforces the need for multiprofessional working and training involving emergency department staff and acute physicians.

The lessons that apply to all health professionals dealing with pregnant women can be summarised as follows:

Understand the physiological adaptations of pregnancy in order to be able to recognise the pathological changes of serious illness – it is important to be able to distinguish between common discomforts of pregnancy and the signs of serious illness so that these signs are not missed ( Table 5.1)

Focus on getting things right the first time – high‐quality history taking, physical examination, meticulous recording of basic observations and findings, and acting on those findings without delay

Remember the red flags, including repeated presentation or readmission during pregnancy

Ensuring good communication and timely, effective referrals between professionals

Table 5.1 Physiological changes and normal findings in pregnancy

Source : RCP (Royal College of Physicians). Acute Care Toolkit 15: Managing Acute Medical Problems in Pregnancy. London: RCP, 2019. © Royal College of Physicians

| Indicator |

What’s normal in pregnancy? |

| Heart rate |

An increase of 10–20 beats per minute, particularly in third trimester |

| Blood pressure |

Can decrease by 10–15 mmHg by 20 weeks, but returns to pre‐pregnancy levels by term |

| Respiratory rate (RR) |

Unaltered in pregnancy If RR >20 breaths per minute, consider a pathological cause |

| Oxygen saturation |

Unchanged throughout pregnancy |

| Temperature |

Unchanged throughout pregnancy |

| Full blood count |

Ranges altered in pregnancy: Hb (105–140 g/l) WBC (6–16 × 10 9/l) |

| Renal function |

Increased glomerular filtration rate Creatinine falls in first and second trimesters Normal urea reference range 2.5–4.0 mmol/l Normal creatinine <77 μmol/l |

| Liver tests |

Raised alkaline phosphatase up to three‐ to fourfold of pre‐pregnancy level is normal during pregnancy |

| Troponin |

Not elevated during normal pregnancy May be elevated in pre‐eclampsia, pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, arrhythmias and sepsis |

| D‐dimer |

Not recommended for use in pregnancy |

| Creatinine kinase |

Normal range 5–40 IU/l, i.e. lower in pregnancy |

| Cholesterol |

Up to five times elevated in pregnancy (therefore should not be checked routinely) |

| Thyroid function tests (TFTs) |

Use local gestation‐specific ranges |

| ECG |

Sinus tachycardia 15° left axis deviation dueto diaphragmatic elevation T wave changes – commonlyT wave inversion in lead III and aVF Non‐specifìc ST changes, e.g. depression, small Q waves |

| Holter monitor |

Supraventricular and ventricular ectopics are more common |

| Chest X‐ray (CXR) |

Prominent vascular markings, raised diaphragm due to gravid uterus, flattened left hemidiaphragm |

| Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) |

Unchanged in pregnancy |

| Arterial blood gas |

Mild, fully compensated respiratory alkalosis is normal during pregnancy |

5.2 Modified early‐warning systems

It is recognised that pregnancy and labour are normal physiological events but ‘normality cannot be assumed without measurement’(Knight et al., 2014). Maternity early warning score (MEWS) systems adapted for pregnancy are designed to detect when there is deviation from the normal. Regular observations of vital signs should be an integral part of care of all pregnant women. MEWS charts should be readily available and used in obstetric and non‐obstetric areas of the hospital where pregnant woman may present.

There is a minimum dataset of observations suggested at each assessment which should be recorded on a MEWS chart ( Algorithm 5.1). The minimum recommended frequency of observations as an inpatient is 12 hourly. Frequency of observations is determined by risk status, initial observations and working diagnosis. Women should retain the same MEWS chart when moving from one clinical area to another, so that physiological trends can be detected.

MEWS scores outside the normal range for pregnancy are recorded in the coloured zones of the chart and should immediately trigger communication using the SBAR (situation, background, assessment and recommendation) communication tool with appropriate medical staff asking for urgent review ( Box 5.1). The clinician should undertake a full systematic review, resuscitate and treat as required and order appropriate investigations. It must be emphasised that just recording observations however regularly or meticulously is not enough: abnormal ones must be acted upon. If the clinician who has been contacted is unable to attend within 10 minutes, options include contacting a more senior obstetrician or the anaesthetic team. Consider early obstetric consultant and anaesthetic consultant involvement. If a senior speciality trainee has deputised a more junior obstetrician to attend, then the midwife and charge midwife need to assess whether this is an appropriate level of clinician attending and consider escalation as outlined. It is important to care for the woman in the most appropriate clinical area. If this is not possible, then a delay in transfer must not delay immediate history taking, examination, investigations, treatment, note review and reassessment of ABCD. Contact the clinical manager on call for assistance if required.

In non‐obstetric areas such as the emergency department or acute medical unit there should be clear routes for effective communication with the obstetric team for allpregnant women. Routes for escalation should be clear to all staff should the woman’s observations on the MEWS chart trigger a review or her condition clinically deteriorates. If a pregnant woman is triaged by the ambulance or emergency department staff to the emergency department resuscitation room a 2222 ‘obstetric emergency’ call (or equivalent) should be activated to ensure a full team including a neonatologist is available.

Читать дальше