Among the new boats were Kriter III, a seventy-foot catamaran built as British Oxygen, winner of the Round Britain Race when sailed by Robin Knox-Johnston (beating Mike McMullen in the much smaller Three Cheers by less than an hour); Pen Duick VI, Eric Tabarly’s boat, built to be sailed in the Round-the-World Race by a crew of fifteen, now being sailed by Tabarly alone; Galloping Gael, a boat designed to the maximum limit of the Jester class and sailed by an Irish/Canadian/American, Mike Flanagan; FT, also designed to the maximum of the smallest class and sailed by David Palmer, who seemed certain he would take the class prize; Spaniel, a hitherto unknown Polish entry, with a bucket seat and automotive steering wheel in her tiny deckhouse; five identical boats designed by Marc Linski, a Frenchman; and four identical thirty-two-foot trimarans designed by Dick Newick especially for the race, one of them sailed by a close friend of Ron Holland’s, Walter Green, an American.

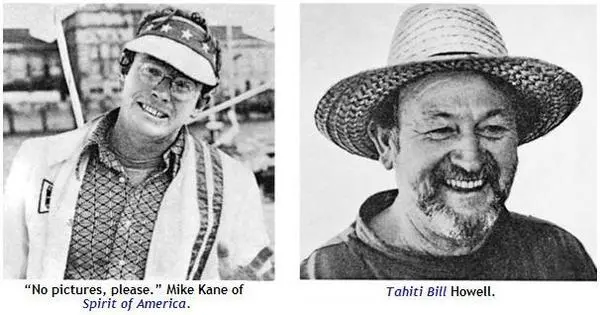

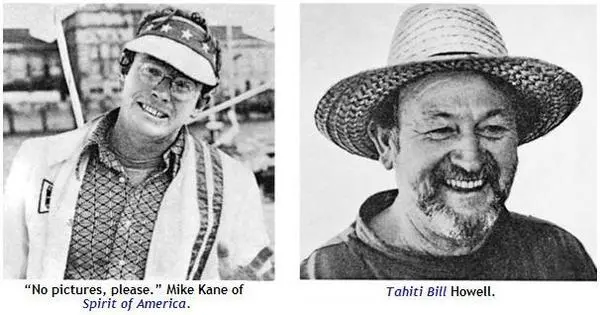

With the withdrawal of Great Britain III and Manureva, only seven boats were entered in the largest group, the Pen Duick class. One of the most interesting was a sixty-two-foot trimaran with a truly vast sail area, Spirit of America, sailed by Mike Kane, who claimed his boat to be the fastest multihull in the world. The medium-sized Gypsy Moth class had considerably more entrants, but by far the largest was the Jester class, with about ninety boats, most of them privately owned, nonsponsored boats like Harp.

Living conditions not being in the category of wonderful in Millbay Docks, I moved into a hotel until the start. On Monday night Angela and I went to a party given by Tom Grossman of Cap 33 and met a number of other entrants. Although we knew each other by sight, this was my first meeting with Mike Kane. He was reputed to be a bit cocky about his boat and his chances, and with a few drinks under his belt he was in rare form, talking about the incredible speeds the Lock Crowther — designed tri could reach and how well proven she was. We lingered a bit too long among the congenial company at Tom’s party and missed Mike and Lizzie at the Club.

TUESDAY. The hydraulic engineer rang and said that Hydromarine would reluctantly supply the needed replacement unit, but that they were insisting he come back and install it. I cringed at the cost, but I agreed. I spent the morning rounding up bits and pieces of gear, including two white fishing floats which would have to be painted black to conform to a last-minute rule that each yacht carry two black balls hoisted when the boat was under self-steering with no one on deck, a concession to the criticism from Yachting World. I was doing this job when the first of the scrutineers, Walter Venning, arrived aboard Harp. “Come aboard,” I said. “I was just painting my balls black.” Then from behind him appeared his girlfriend, Sally, the other scrutineer. I think I blushed.

They asked to see all the required safety equipment, checking each item off on a list, then chatted for a minute. Walter turned out to be a cousin of Bill King’s, whom Bill had told me about. He is a tomato grower, and once, when Bill was about to make a transatlantic crossing in his first boat, Galway Blazer I, Walter gave him a basket of tomatoes which had been carefully selected so that one of them would ripen each day. It had worked perfectly, Bill said, the last tomato ripening on his last day out.

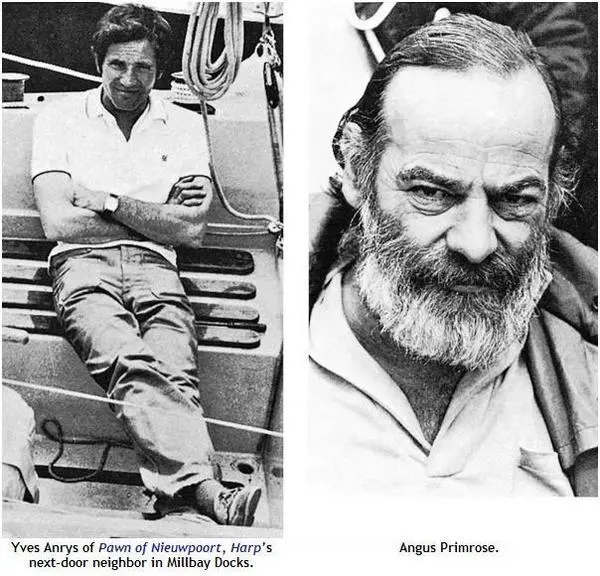

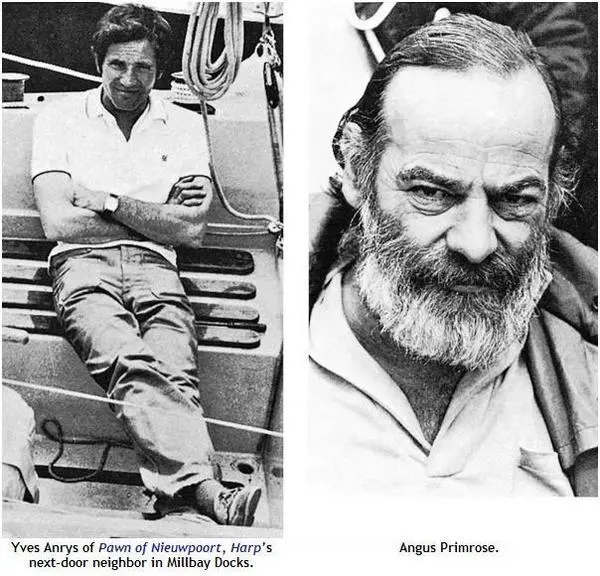

Yves Anrys and I had a chance to talk a lot as we were each doing jobs on our boats. Yves had been a reserve Olympic helmsman in the single-handed Finn dinghy class and was sailing a half-tonner similar to Harp but very stripped-out inside and much, much lighter. He is a merchant seaman and was planning to race his boat in the World Half-Ton Cup Championships later in the year.

WEDNESDAY. I was a blur of motion all the morning, running errands, seeing to last-minute fittings, and filling small gaps in my list of necessary gear. There seemed to be no end to it, and I was beginning to have a feeling of running out of time. While in this somewhat harassed state I got a telephone message from the Royal Western office in Millbay Docks that the McWilliams and the Hollands were arriving at four in the afternoon and please to meet them.

We arrived back at Millbay Docks and were standing outside the Observer press office, chatting with some people, when Angela called me aside. “Have you heard about Lizzie McMullen?” she asked. Oh, God, I thought, there’s been a car crash and Lizzie’s in the hospital with a broken leg or something.

“No,” I said.

“There’s been a terrible accident. Mike and Lizzie were working on the boat at Mashford’s yard this morning when an electric drill fell overboard into the water. Mike shouted for her not to touch it, but she did. They gave her heart massage and artificial respiration for half an hour until an ambulance could get out to Cremyl, but it didn’t help. She was dead on arrival at the hospital.”

I froze inside; I couldn’t believe what she was telling me. Lizzie McMullen, beautiful, bright, delightful Lizzie, could not be dead; it was simply not possible. I asked Angela if she were absolutely sure, if there were any possibility of a mistake. Angela was sure. Lizzie, who thirty-six hours before had been joking about my central heating, laughing, and sipping sherry on Golden Harp, was gone. Irrecoverable. Out of anyone’s reach. Out of my life. Out of Mike’s. Dear God, I thought, if I feel this way, as if somebody had struck me with a blunt instrument, how must Mike feel?

“How is Mike?” I asked Angela.

“I don’t know. I’m sure friends are with him. I’ve sent a telegram.” I wanted to send a telegram, too. I sat in Angela’s office and thought for a time. There were less than seventy-two hours left before the start of the race. This would have been the most crushing possible blow at any time, but to happen now, after four years of work and preparation together. It suddenly seemed unthinkable that Mike should not sail the race. I found a pencil and wrote, “I only knew her for a week, and I loved her, too. There is no answer to the senseless. Please sail the race and win it.” I signed the telegram, gave it to Angela to send, then went out and sat in the car, numb. A man wandered over and began talking to me through the open sunroof about an ice cream seller who had been ejected from the docks because he didn’t have the proper permit. I chatted absently with him without knowing what I was saying. Angela came out and we talked for a moment, then I left. I felt I had to keep doing things, that I couldn’t stop — not just because I had so much to get done but because if I stopped I would think about Lizzie and, worse, about Mike. So I kept moving, kept ticking items off my list, but it seemed that every two or three minutes I would stop and realize all over again that Lizzie was dead, and it was just like being told for the first time.

I spent most of the afternoon with the Hollands and McWilliams, but in a kind of daze. When they left for the airport early that evening, I went to the club. I found Lloyd Foster and asked if he knew Mike’s plans about the race. “I think it will certainly be impossible for Mike to compete now,” he said. “Of course, there’s the funeral, but there’ll have to be an inquest as well. There are just too many formalities to complete before Saturday.” I suggested that the competitors might send some flowers, and Lloyd agreed to receive contributions. Later, that didn’t seem enough, seemed too transient, and some of us thought perhaps the committee might accept a new trophy for multihulls to be presented in memory of Lizzie. This seemed much more satisfactory, more permanent, and Lloyd said he would bring it before the committee for consideration.

Читать дальше