Mike Kane came to the dockside, camera crew in tow, and we had a shouted exchange of good-natured abuse for the benefit of the television audience. Robert Hughes arrived and replaced the steering vane shaft which had been bent in the altercation with the customs launch in St. Mawes. Everything was finally aboard and fitted; only some stowage remained, and we left that for the following morning.

Ann and I had hoped to have a farewell dinner at the superb Horn of Plenty in Gulworthy, but we finished on the boat too late and decided on dinner at Bella Napoli after a drink at the Royal Western. There we bumped into Jerry Cartwright, the well-known yacht designer and bottom pincher, and a very attractive English girl, Suzy Wassman, who had lived for a time in Newport. They joined us for dinner. Jerry had done the last OSTAR but hadn’t been able to complete a boat in time for this one, and we talked all through dinner about the race, the routes, and problems I might encounter. I had missed most of the weather briefing that afternoon, turning up at the wrong place, but everybody I talked to still seemed to think it was a toss-up between routes. Only a smaller-than-usual amount of ice on the great circle made that route seem a possible favorite. I was still leaning toward the Azores route, having heard nothing new against it, but still had not made a final decision. I would not really have to do that until leaving the Channel.

I was also bitching a lot about the handicap I had been assigned that afternoon. Nobody knew what handicapping system the committee was using, but whatever it was, I didn’t like it. Harp had been given a handicap of nineteen days and some hours; Pawn of Nieuwpoort, Yves Anrys’s boat, identical in size to Harp but stripped out inside and much lighter, had been assigned a handicap of twenty-two days and some hours. I was giving Yves three days! Clare Francis, in her thirty-eight-foot Robertson’s Golly, was giving me only half a day! When Yves and I sat down and went through the list, we discovered still more strangeness. Harp, designed as a half-tonner, was actually giving time to a one-tonner! I had written out an immediate protest to the committee, citing half a dozen apparent anomalies, and they had told me I would get a decision in Newport. I was very concerned about this, because the handicap prize was the only one Harp had any real chance of winning, being eight feet overall and three and a half feet on the waterline shorter than the class maximum.

In spite of all the shoptalk, the pleasant dinner eased the tension a bit and, since Jerry would be on the press boat at the start, we invited Suzy to join Ann and me on Harp for the time before the start. That way she could get inside the restricted zone, where spectator craft were not allowed.

Tomorrow was the day, but I was too tired at bedtime to reflect much about it.

SATURDAY AND THE START. We were up at six; collected my fresh meat, a week’s supply, from the hotel freezer, where it had not frozen; stopped by the fish market for a large bag of ice, which smelled like fish; and got down to the boat. I dropped Ann, the meat, and the fishy ice there and drove to the marina, where Mike Kane had promised me some last-minute weather poop. Mike was late and I had too much to do to wait, so I went back to Millbay Docks, giving Richard Konklowski, the Czech entry, a lift. I hadn’t had an opportunity to talk with Richard before, but he was an interesting fellow, sailing his little home-built twenty-four-footer, Nike, in the race for the second time. Since the Czechs have no boat-building industry and import restrictions abound, Richard had had to build his boat from whatever materials he could find, making many fittings himself, even the sails.

Since repairs on Harp ’s engine had been completed so late, there had been no opportunity for the committee to seal the gear lever, and I was given an acceptance certificate and told they would trust me. (As it turned out, they didn’t have to.) This meant that, unlike the other competitors, we had a useable engine for the period before the start and did not have to be towed. So, with Ann and Suzy aboard, we were among the first out of the docks, collecting a round of applause from the crowd gathered at the gates. (Angela told me later that all the competitors got a round of applause. I had thought it was just for me. )

We motored out to the starting area, stowing gear all the while, and started to look at boats. I don’t think anybody got a better look at things than we, with our engine. We motored back and forth through the fleet, dodging hundreds of spectators that could simply not be kept out of the restricted area, in spite of the best efforts of the Royal Marines, buzzing about in inflatable assault craft, yelling at people. There was every possible kind of spectator boat inside the restricted area, most of them small yachts under power, but I even saw two kids in a Mirror dinghy thrashing about among the competitors.

In spite of what sounds like chaotic conditions, everything was quite orderly, the spectators were well behaved, apart from their trespassing, and I did not see a single incident of any kind. Fortunately, it was a light day. In heavy weather things would have been a bit hairier, but then, in heavy weather, there would not have been so many spectators.

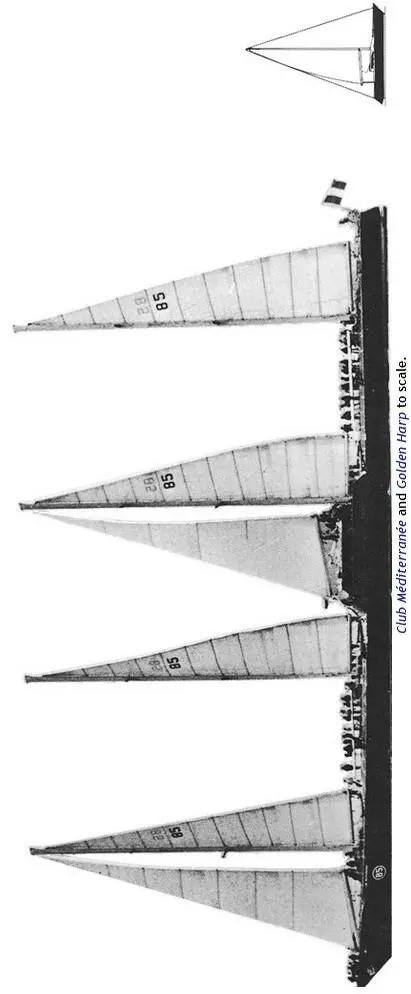

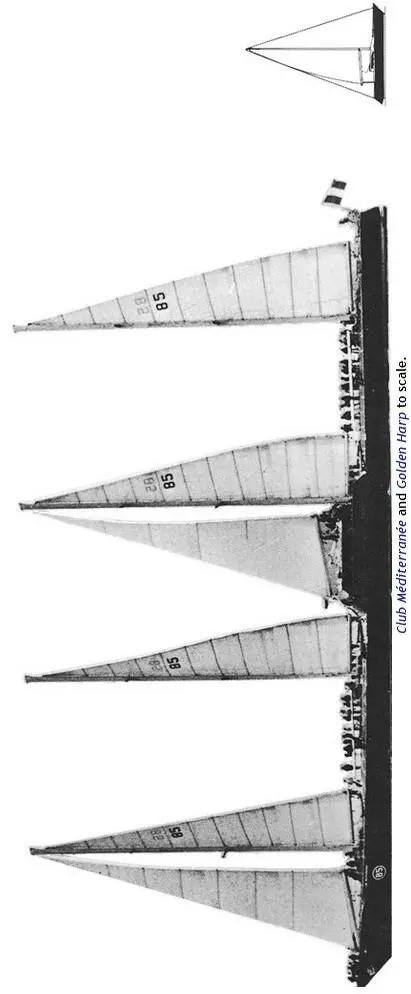

Club Méditerranée sailed slowly around at the starboard end of the line, her decks crawling with people (spectators did not have to be off the boats until the ten-minute gun), and Spirit of America stayed nearby. I knew Mike Kane wanted badly to start before Colas, and there he was, waiting.

The ten-minute gun went for the big class, and the huge boats started jockeying for position. ITT Oceanic, sailed by Yvon Fauconnier, was down at the starboard end of the line with Club Med and Spirit, and the other large boats were more scattered. Poor Tom Grossman, on Cap 33, had been bumped up from the Gypsy Moth to the Pen Duick class when it was found that his boat exceeded the length for the medium class. He had simply taken the word of the previous owner on her measurements, and now he was in with the big boys, the smallest boat in the class.

Seconds before the gun I saw Mike Kane get Spirit into irons nearly on top of the starting line. He just stood in the cockpit shaking both fists in the air until the big tri decided which tack she wanted. Fortunately for Mike, Colas was late, and Spirit recovered in time to nip Club Med at the line. Then Spirit was gone, reveling in the light conditions, while Club Med moved sluggishly toward the Channel. It was clear that if it were going to be a light-weather race Mike would probably win it hands down.

Mike McMullen sailed past in Three Cheers, and I shouted to him, “Win it, Mike!”

“I’ll bloody well try!” he shouted back. He was smiling.

As soon as the Gypsy Moth bunch were away I put Ann and Suzy off onto a spectator boat, switched off the engine, and began to sail slowly around under main only, the reefing genoa furled, and the drifter lashed on deck in case the wind dropped. I have never experienced anything quite like the atmosphere among the competitors at the starting line. Here, in an intensely competitive situation, everybody was wishing everybody else luck! Each time two boats passed there were shouts, jokes, and absurd insults exchanged. I saw and exchanged greetings with Nigel Lang, Ian Radford, Max Bourgeois, Peter Crowther, Angus Primrose, Andrew Bray, Richard Konklowski, Richard Clifford, Ziggy Puchalski, Mike Flanagan, Simon Hunter, and two dozen or so others whom I had never met but were wishing me luck, anyway.

Читать дальше