In addition to the list of things I had planned to do in Plymouth, new problems kept cropping up: first, the hydraulic drive problem, then the engine’s electrical system. An electrical engineer came aboard and immediately found the problem which had caused my batteries to discharge: one of the battery wires had been led across part of the engine’s exhaust system which, when it got hot, had burned through the insulation of the wire, causing a short circuit.

On Saturday night Angela and I invited Mike and Lizzie McMullen to come aboard Harp for drinks. They were tied up until later in the evening, so Angela and I had dinner at Bella Napoli, which was becoming a sort of culinary headquarters for everybody, and went back to the boat to wait for them. They were late, and as we were sitting below having a drink, we heard a commotion from across the marina. I stuck my head through the hatch and looked around. Two pontoons away a large group of dark figures was gathered around another boat, some of them pounding on the coach roof, others pumping up and down on the bowsprit, pitching the boat fore and aft. I heard someone shout above the din, “Aha! We know what you’re at!” I went back below, laughing, and told Angela that some poor bastard across the way was having either his sleep or his amorous activities disturbed by his friends.

A few moments later I heard hushed puzzled voices on the pontoon next to Harp and stuck my head out again to see what was up. Mike and Lizzie and half a dozen other people were standing there, trying to figure out where Golden Harp was. Forgetting that Harp was an Irish entry, they had asked at the marina office for the American boat and had been directed to Catapha, whose skipper, David White, had been rudely awakened by a great deal of noise and commotion. “What really worried me,” Mike said, as they all tumbled below and found seats, “was how big that guy was.” Andrew and Roslyn Spedding, close friends of the McMullens’, had come along, together with David Hopkins and Paul Weychan, designer and builder of Quest, a fast-looking trimaran which would be sailed by John deTrafford. There were a couple of other people jammed into Harp as well, but in the ensuing joking and laughing I forgot their names. Andrew Spedding had sailed in the last OSTAR, and was one of the scrutineers who would be inspecting Harp in Millbay Docks. I tried to keep his glass full.

At one point in the evening I remember Mike remarking, “There’s a lot of luck involved in this race.” It was a comment I had not heard anyone else make, and I would have occasion to recall it later.

MONDAY. I spent the morning doing small jobs on the boat. The marina mechanic, Ted, came and changed the engine’s water pump, which had been leaking, and installed a new Jabsco electric bilge pump.

Ian Radford volunteered to come with me on the tow to Millbay Docks and help me berth Harp there, which might be tricky with no engine and so many boats about. Ian is a young physician who had been practicing in Zululand and who had done a stint performing heart surgery with Christiaan Barnard in South Africa. He had accepted a new job in Miami, Florida, and was emigrating the hard way, via the OSTAR. A cheerful soul, Ian was always ready to lend a hand with no more recompense than a cold beer or two... or three.

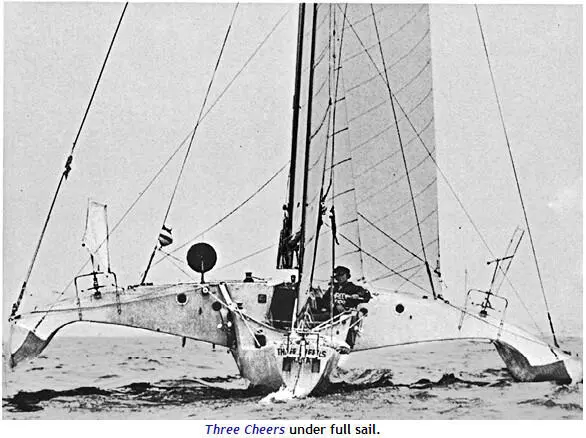

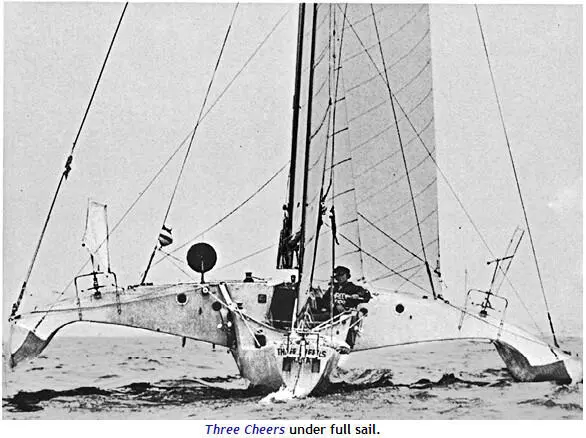

As we were waiting for the towing vessel to come for us, Lizzie trotted up, a bottle of whisky in each hand, and invited us to come for a look at Three Cheers. The lovely, primrose-yellow trimaran was tied up at an outer pontoon of the marina, where she had just been blessed by the family vicar. The bottles of booze were gifts from friends who had turned up for the ceremony. Nigel Lang of Galadriel, one of the little Contessa 26s in the race, joined us, and we spent a pleasant half hour aboard as Mike, with obvious pleasure and pride, gave us a Cook’s tour of the boat. I had only been on one or two tris, and I was fascinated as Mike explained the modifications he had made which would make her an even faster boat than when Tom Follett had sailed her. I lifted an upside-down bucket in the cabin and found a small ham-type shortwave radio transmitter. He was keeping the bucket over it, Mike explained, because he had not had time to get a license for it, and anyway, he would only use it in emergencies. Nigel remarked on the absence of stanchions and guardrails on the boat, but Mike pooh-poohed the idea, saying he thought they were unnecessary.

We finished our tour and Ian and I invited Lizzie to stop by Harp for a glass of sherry on her way home, since she was passing the boat, anyway. Lizzie, who had been fascinated with all the little comforts on Harp compared to the austerity of the lightweight Three Cheers, rolled her eyes and said she’d just love to come and see my central heating and listen to my stereo again. I said she could snuggle up to my central heating anytime, and as we left Mike shouted after us, “You watch that fellow. I don’t trust anybody who has central heating and stereo on his boat!” We left Three Cheers, Lizzie giggling, and strolled along to Harp. We had sat and chatted for only a minute when the towing vessel turned up, and we had to cast off. As Lizzie jumped ashore we agreed that Angela and I would try and meet them at the club later that evening for dinner. “Don’t forget to bring your nose!” I shouted after her as she ran toward the car park, still clutching the whisky.

She laughed and waved the bottle. I was looking forward to spending another evening with the McMullens.

John, the marina’s bosun, towed us slowly around to Millbay, and as the gates were not yet open, we had an opportunity to circle and get a close look at Club Méditerranée. From the water she seemed even more massive, with her four tall masts, enormous deckhouse, and huge windcharger propeller aft. Alongside her, Golden Harp looked about the same size as the little Avon dinghy we were towing looked alongside Harp. As we waited for the car ferry from France to dock and the Millbay gates to open, other yachts began to congregate in the area, and by the time the gates opened a dozen or more boats of all sizes were there, this being the final deadline for entering the docks without incurring a time penalty.

Inside, Captain Terence Shaw, former secretary of the Royal Western, who was in charge of docking arrangements, directed us to a berth alongside Pawn of Nieuwpoort, being sailed by the Belgian entrant, Yves Anrys, and Achille, whose skipper was the young Frenchman, Max Bourgeois. Terence Shaw, white-bearded and very salty-looking, did not need a megaphone to issue his instructions, and skippers disregarded them at their peril. Soon, Nigel Lang, in Galadriel, and young Simon Hunter, in Kylie, another Contessa 26, were tied up outside us, making a raft of five boats, with Achille closest to the concrete dockside.

Behind us were the two Chinese lugsail schooners, Ron Glas (which is Gaelic for “gray seal”), sailed by Jock McCleod, a Scot, and Bill King’s old boat, Galway Blazer II, now owned by Peter Crowther, who is just a bit mad. Also there was Angus Primrose in a Moody 33 of his own design, Demon Demo, soon joined by Chris Smith in the tiny Tumult, only twenty-two feet long.

Millbay Docks was now home to nearly every boat that would start, and the whole place took on a festive air that completely changed the ordinarily drab appearance of the place. Angela and her Observer press office were there; Camper & Nicholsons and M. S. Gibb were sharing a portabuilding, and Brookes & Gatehouse were located in a trailer nearby. All the famous boats from past races were there: Jester, the Chinese lugsail folkboat which had been sailed in every OSTAR, first by Blondie Hasler and later by Michael Richey; Tahiti Bill, Bill Howell’s cat; Vendredi Treize, the 128-foot giant of the last Race, now called ITT Oceanic; Cap 33, formerly a French trimaran, now sailed by an American from Boston, Tom Grossman. Manureva, in which Alain Colas had won the last Race, was to have been sailed by his brother, but had lost a float and would not compete.

Читать дальше