The slaving aboard the boat was relieved by an increasingly active social life as more and more competitors arrived. The bar at the Royal Western was getting more crowded by the day, and nobody talked about anything except the race — especially what equipment different boats were carrying and, most of all, the riddle of which route to take.

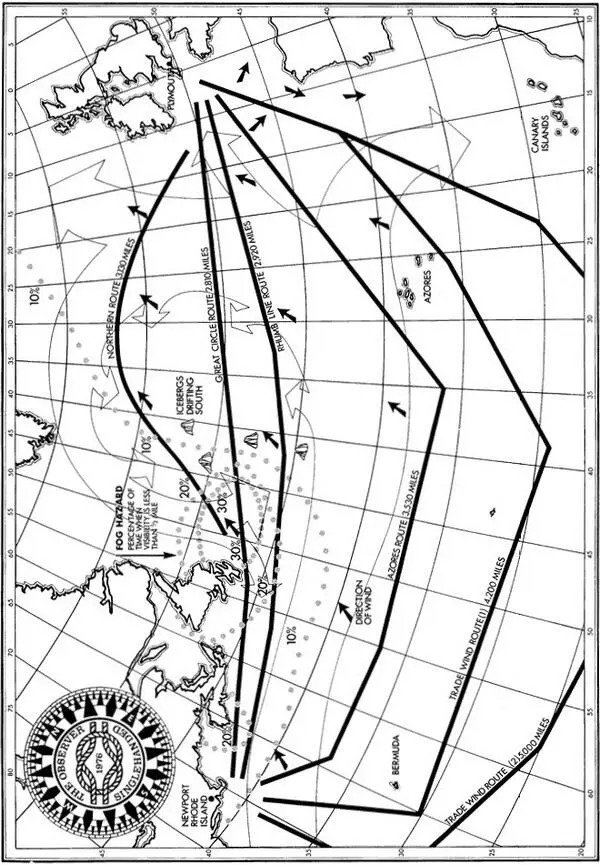

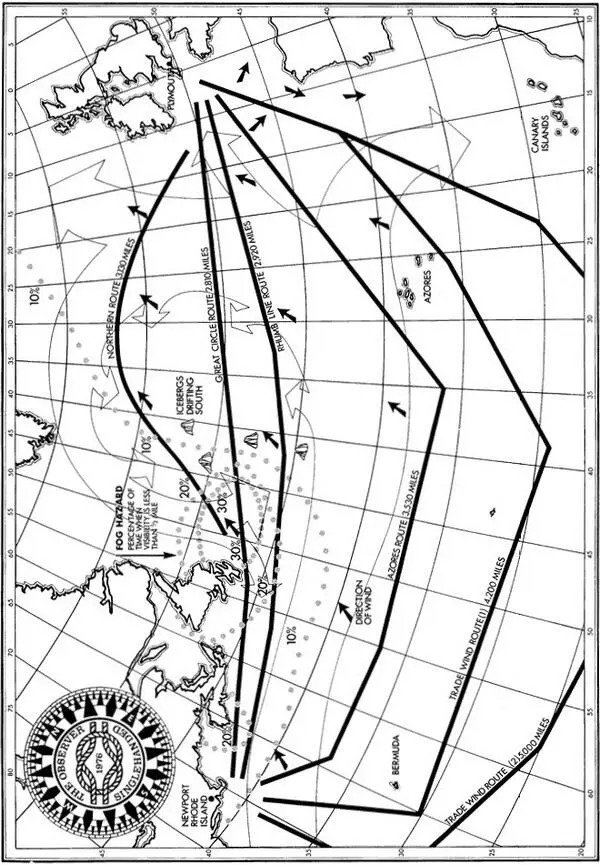

There are two main routes taken by most competitors and several variations. The most-sailed route, and the one which had always been sailed by the winning yacht, is the great circle route. Its principal attraction is that it is the shortest, about two thousand eight hundred miles. But it has great disadvantages, too: the weather can be very rough at times, there is the likelihood of icebergs and fog along the way, and, worst of all, a skipper taking this route must expect headwinds nearly all the way, and he must tack back and forth in order to get west, since a sailboat cannot sail straight into the wind. This circumstance can add several hundred miles to the distance actually sailed.

The second important route is the southern, or Azores, route. This involves setting a southwesterly course to and past the Azores, down to about latitude thirty-seven degrees north, then turning west and sailing to about longitude sixty-five degrees west, before turning northwest for Newport. On the face of it this route sounds silly, since it is about three thousand five hundred miles long, but it does have its advantages. In a year of typical weather, a skipper will have a lot of reaching winds and not nearly so much beating to windward as on the great circle route, and thus should be able to sail much faster. Nobody taking this route had ever won the race, but in each race somebody always came close, and often it turned out that boats taking the Azores route sailed fewer miles than boats which had had to tack back and forth on the great circle route. Another major attraction for the Azores route is kinder weather and lots of sunshine, and, of course, the Azores themselves are on the route in case a boat suffers damage or her skipper is injured. The big disadvantage of the route is the big Azores High, which, in addition to providing sunshine, can also provide extended periods of calm, and sailboats do not sail in calm weather: they sit on the sea, occasionally being pushed in the wrong direction by ocean currents.

There are variations, as I have mentioned: there is a high, northern route, where some hope to pick up following winds, but the risk of ice is much higher; and there is the very southerly trade winds route, which offers almost certain free sailing, but which is so long that it has rarely been taken in the race. The big joker in the pack is the Gulf Stream, a strong ocean current which originates in the Gulf of Mexico, runs around the tip of Florida, up the east coast of the United States, turns northeast and continues across the Atlantic toward the British Isles. Anyone trying to sail a route between the great circle and the Azores routes will have to contend with this major, adverse current, and most prefer to avoid it, those on the great circle route remaining north of the stream, and those on the Azores route remaining south of it, until crossing the current almost at right angles when turning northwest for Newport. The excellent chart from the official race program is reproduced here and illustrates all the various routes.

Many people had already made the decision to plunge straight across via the great circle, no matter what; others would not consider any route but the Azores. I was undecided, preferring to wait for the weather briefing the day before the race before making a decision, but I was biased toward the Azores route. Harp went well in light moderate airs, and I felt my level of experience was probably better suited to going south.

I had had some advice from the Irish Weather Service, who had kindly sent me some charts and diagrams and reported on some studies of westerly winds in the North Atlantic, but the sum total of all these was that nobody could predict anything about the weather we would encounter with any degree of probability, let alone certainty. So I would wait for the final briefing, in the meantime soliciting as many opinions as possible — and there were almost as many opinions about the route as there were competitors. There was a great deal of caginess in any discussion of route, nobody being willing to commit himself on the subject. If somebody did commit himself he was probably lying and would be taking another route on the day. This caginess always made me laugh, since the whole question was so riddled with uncertainty and the weather on any route so unpredictable that it seemed to make little difference what anybody thought before the Race.

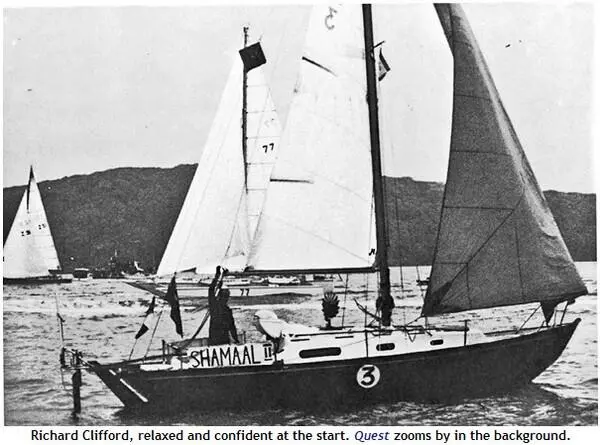

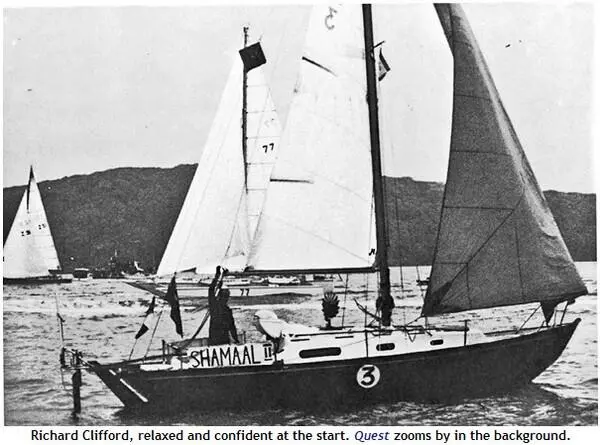

On Tuesday night, Richard Clifford invited me aboard Shamaal II, on which he lived, for drinks. It was a big party for a small boat, comprising Richard; myself; Robert Hughes, the Gibb self-steering expert; two other Royal Marine officers; the Bulgarian entry, Georgi Georgiev; and two people who were to have a large effect on my life, Mike and Lizzie McMullen. Mike was sailing Three Cheers, a fast trimaran designed by the very successful Dick Newick. His practice crew, David Hopkins, was also there.

Mike McMullen had sailed Binkie, a thirty-two-foot monohull, in the last OSTAR and had finished well up. While in Newport he had been invited for a sail on Three Cheers by Tom Follett, who had sailed her in the race. Mike had been instantly attracted to the boat, although he had never sailed a multihull, and bought Three Cheers and immediately began to sail her in preparation for the next OSTAR. Lizzie had enthusiastically joined in the project and they had spent a great deal of time together on the boat during the ensuing four years. The previous summer they had made an extended cruise to the Hebrides and made a film about it which was soon to be shown by the BBC. Mike was a tough, former Royal Marines commando officer and a superb yachtsman, and his ability, in combination with such a fast and proven boat as Three Cheers, had made him one of the favorites to win the race outright, in spite of the fact that Three Cheers, at forty-six feet overall, was much smaller than the other favorites.

I was attracted to Mike and Lizzie McMullen as I have rarely been attracted to any couple, their collective charm, enthusiasm, and total commitment to the race captivating me completely. Mike held forth on his opinions about the OSTAR and Lizzie goaded him from the sidelines; we talked and talked and laughed constantly. Lizzie was a very beautiful girl, and I complimented her on her nose. (There are leg men, etc., etc. I have always been a nose man.) She liked that, and it became our private joke.

We eventually continued the party in the bar of the Royal Western, and by the end of the evening I counted them as close friends, difficult as that may be to explain. For ten days I would see them constantly, then I would not see them again.

Angela Green of The Observer arrived to set up the press office, and we began to see a great deal of each other, often meeting Mike and Lizzie in the club for drinks and another discussion of the race.

Harry had flown back to Ireland the day after our arrival, and now O.H. had to leave, too, so I was on my own. I greatly envied those entrants who seemed to have whole staffs of people to fetch and carry and bolt things onto their boats. Even some of the smaller boats had vans full of gear and teams of friends, relatives, or professionals working on their problems. Ann was coming down the Thursday before the race, but until then I would have to get help where I could find it. Robert Hughes, in addition to servicing Fred, was most helpful with stowing my food, and Ian Radford, who was in the marina aboard his entry, Jabuliswe, and who was much readier than I, was very helpful. The marina staff did what they could, and Alec Blagdon loaned tools from his boatyard, even though I did not have to take Harp there for anticipated repairs. But by the end of the week, although a great deal had been accomplished, my list of things to do did not seem any shorter, and Harp would have to be moved into Millbay Docks on Monday night, along with all the other entries, to undergo her three inspections — one for water and stores, one for safety equipment, and one for structural soundness and suitability of gear. She would also have to be inspected by the handicap committee, and the gear lever of her engine would be sealed, so that the engine could be driven only in neutral, for battery charging.

Читать дальше