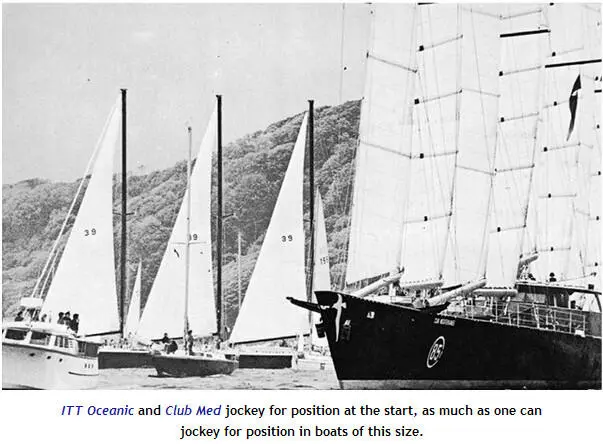

I saw Angela, aboard one of the Observer press boats, and waved goodbye. We were planning to meet in Newport, where she would be running another press office at the other end. I saw the boat carrying Ann and Suzy a couple of times more, and then I heard the ten-minute gun. I had chosen the starboard end of the line, because starting on the starboard tack would give me right of way over boats on the port tack. I ignored all other tactical considerations in favor of playing it as safely as possible. With nearly ninety boats on the line it would be all too easy to collide with somebody and be out of the race with damage before it even started. In spite of my decision to play it safe, though, I felt all my dinghy racing instincts coming back as the minutes ticked away; I stopped thinking about safety and started thinking how to be on the line when the gun went. Suddenly, nothing else mattered.

I made a couple of passes at the line under main only, then settled into an oval pattern near the starboard end, jibing around in circles and watching my stopwatch. At about a minute and a half to go, I found myself being crowded by the Linski boats, all five of them, which seemed determined to start as a fleet. At forty-five seconds I let go the tiller and hauled on the leeward sheet, breaking out the reefing genoa, and started for the line. I crossed exactly thirty seconds late. Lousy for a dinghy start, but pretty good under these conditions. Much better yachtsmen than I started way behind me.

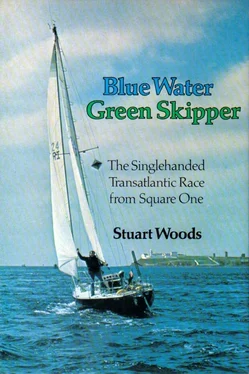

Nineteen months, almost to the day, after my first offshore passage in a yacht, I was starting across the Atlantic, single-handed. I felt as if I would explode. I felt terrific.

As I crossed the line I overtook and sailed between Richard Konklowski in Nike and Michael Richey in Jester, with only a few feet to spare on either side. After that I was in the clear and had only to worry about yachts approaching on the port tack. I was making about three knots in the light breeze, very good considering Harp was wearing the number-two genoa instead of the number-one. I had set the smaller sail at the start because it would be more manageable in tight quarters.

I sailed perhaps three miles into the Channel in order to lay Penlee Point with plenty of room to spare, noticing that I seemed to be sailing as fast as Clare Francis in Robertson’s Golly, which was carrying a bigger sail. Just before I tacked, Walter Green in the Dick Newick tri, Friends, sailed across my bows, moving very fast. Conditions were ideal for the trimarans, and shortly after I tacked, David Palmer in FT overtook me to leeward, having apparently got a very bad start. Just after we crossed the line, Peter Adams and his family motored alongside in their small yacht and we made our goodbyes. Now another familiar yacht, Ruinette, from Cork, called me on the VHF and wished me luck. It was my last such contact that day, and I felt I was really on my way.

Up to windward Yves Anrys in Pawn and Lars Wallgren in Swedelady were giving me a boat-for-boat race. Yves, with his big genoa set, began to pull away from us, and Swedelady began to change up to a bigger sail. I hung on to the number-two, hoping the wind would freshen, and Yves pulled away from me. Then Ian Radford in Jabuliswe appeared astern and began, very slowly, to overtake me. She was a smaller boat than Harp, and I knew if I didn’t get more wind soon I would have to make the sail change. Because of the furling gear, this was a more difficult change than with conventional gear, and I dreaded losing the time without a foresail during the change. In higher winds when a smaller sail was needed I would have the advantage, but at the moment, in about a Force three, I did not. Ian was right forward in the pulpit of his boat and stayed there for a long time, apparently making some repair.

Then the wind dropped a bit, and I had no choice but to make the sail change. Once Big Jenny, as I called the number-one, was up, our boat speed increased and we were making a good four knots. Then the wind freshened again and we did even better. About five in the afternoon, off Fowey, we overtook Angus Primrose in Demon Demo, a bigger boat, and I knew we were doing well. Ron had said that Harp would do better than the Moody 33 on any point of sailing except reaching, and it appeared he was right. Shortly after that, David Pyle in Westward, one of Angus’s Moody 30s, just nipped me, but when I tacked again I saw that I was pointing much higher than he, and later I was sure that we had overtaken him.

Darkness fell and there were lights everywhere. There was one yacht in particular that seemed to be keeping pace with us and I thought it must be Ian, in his smaller but much lighter boat. Nobody could sleep that night while we were still in danger of colliding with one another or with shipping in the Channel.

I drank coffee to keep awake, although I had some Dexadrene should I need it, and dined on ham sandwiches and chili con carne that Ann had made in Plymouth. In fact, with a dozen sandwiches and a large pot of the chili, I ate little else for the first three days, except cereal for breakfast. I saw very little shipping, but there were yachts all around us.

At midnight I called Lizard Coast Guard to check the visibility there and was told it was eight hundred yards. By two a.m. it was down to two hundred, but it must have lifted, because I saw the Lizard light briefly at three a.m., then it disappeared. When dawn came, I could see only two yachts as we approached the Lizard, and they soon disappeared after tacking. I did not know it then, but they were the last I would see. The Lizard was really socked in, although visibility on the water seemed about a mile. I came close enough to the headland to hear the fog signal, but I never saw the land at all. It would be some time before I saw any land again.

I tacked away from the Lizard, got the yacht on course, and began making telephone calls on the VHF. It was my last chance to say goodbye to people before I was out of range of Land’s End radio. It was still very early morning in the Channel, but in the States it was five hours later. I heard a British warship on the VHF to somebody, reporting that some of the larger yachts had been reported at the Scillies, and I chatted with Andrew Bray on Gillygaloo . We arranged a calling schedule for noon GMT, but I slept through two of the appointments, and we did not make contact again. I talked with Chica Boba, an Italian yacht, which was apparently behind me. Andrew had been ahead. Late in the afternoon I spotted a Scottish yacht, Sundancer, not a competitor, called him up, and was told that he had seen FT near Bishop Rock, which indicated to me that David Palmer was disregarding his earlier, hotly declared intention to go south.

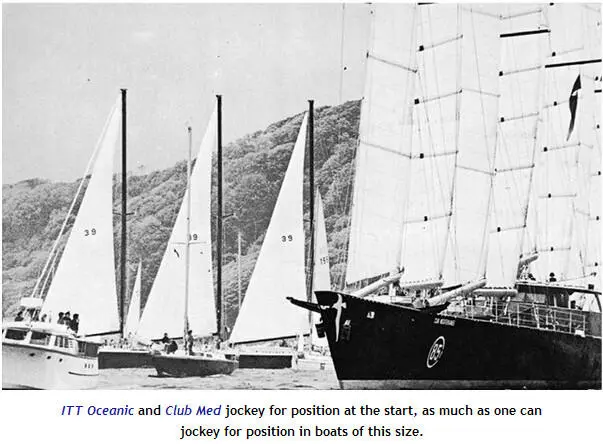

A large group of dolphins came and played with us for half an hour or so, then darkness fell again and I faced my second night without sleep. At midnight I heard a very clear VHF transmission from a ship called Arctic Seal, who was talking with the Coast Guard. When his transmission was finished I called him up and had a long, friendly conversation with the officer on watch, Jerry Miller of Port Arthur, Texas. I could see the brightly lit ship several miles off my port beam and he reported that he could see me on radar at a distance of eight miles, and could see my masthead light as well. This was most comforting. He also gave me a very precise position from his satellite navigational system, which amused me, since Alain Colas had not been permitted to carry that equipment on Club Med and had shown a good deal of annoyance toward the perfidious British because of it. I had been able to see Club Med for a large part of the first afternoon, and I knew she could not be liking these conditions. I said goodbye to Arctic Seal and set a course for the southwest, having made my decision to take the Azores route.

Читать дальше