The potential for digitalization in the library system is huge. The Bodleian has signed a deal with Google to digitize more than a million books and has already scanned about half a million of them. The benefits have already been seen, as it’s opened up huge ranges of nineteenth-century books that sat unseen on shelves for 150 years. Richard Ovenden is excited about the future.

‘It’s always been part of what we see as “serving the whole republic of the learned”, as Sir Thomas Bodley put it — sharing our knowledge. There’s no point in having this great body of information if you can’t give access to it.’

Although libraries in various forms have been around since ancient times, it was only in the nineteenth century that the truly public library, paid for by taxes and run by the state and freely accessible to everyone, came into being on a large scale. Before that, libraries were predominantly the private collections of individuals, or belonged to religious or educational institutions, and weren’t open to the general public.

The Victorian era was the era of self-improvement and education of the masses, and public libraries played a central role. As did a man whose name became synonymous with the movement: the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie emigrated to America from Scotland and became one of the richest men in the world. A sort of nineteenth-century industrial tycoon version of Bill Gates, he spent forty years amassing a huge fortune from iron and steel, and then started to give it away for the public good. ‘The man who dies thus rich, dies disgraced,’ he wrote and, good as his word, by the time he died in 1919, he had poured more than £70 million into educational and scientific ventures, including the building of nearly 3,000 free libraries, principally in the USA and Britain.

It’s an archetypal Victorian rags-to-riches story and a classic tale of the American dream. Born in 1835 in Dunfermline in Fife, Carnegie was the son of a weaver. The family was poor, and Andrew’s father struggled to find work when the steam-powered loom arrived and took business away from the hand-loom weavers. So they took a gamble, borrowed money for the passage, and father, mother and two sons emigrated to America in 1848 and settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie supported the building of more than 3,000 public libraries

From that day forward, twelve-year-old Andrew worked and worked and worked, pulling himself up by the bootstraps through a series of jobs, starting as bobbin boy in the same cotton factory where his father found work. Then he became a messenger boy in the Pittsburgh telegraph office, doing everything he could to get ahead, including memorizing the city’s street lay-out and the names and addresses of the important people he delivered to.

The only formal education Andrew Carnegie had was three or four years at a small school in Dunfermline, but throughout his life he was passionate about education. He attended night classes when he could, and when he delivered telegrams to the theatre he used to stay on and watch the plays.

And he read. Books were his passport to educating himself and making his way in the world. In his autobiography he paid tribute to a Pittsburgh gentleman called Colonel Anderson, who had a private library of about 400 books which he would open to local boys every weekend and let them borrow any book they wanted. This generosity stayed with Carnegie throughout his rise to power and wealth, and inspired his own library philanthropy. ‘Only he who has longed as I did for Saturdays to come,’ he wrote later, ‘can understand what Colonel Anderson did for me and the boys of Allegheny. Is it any wonder that I resolved if ever surplus wealth came to me, I would use it imitating my benefactor?’ He gifted his first library to his home town of Dunfermline. Carnegie gave £8,000 for the building, his mother laid the foundation stone, and it opened in 1883. It was an instant success, and by the end of its first day it had issued more than 2,000 books. This was the pattern that Carnegie followed through the years: he would build and equip the library, but the deal was that the local authority had to match that by providing the land, and coming up with the budget for operation and maintenance. He wasn’t just handing out money willy-nilly; he wanted the state to take on the library after he made it possible. And as a further condition to funding, local councils had to adopt the Public Libraries Acts, which, from 1850, gave local councils the power to establish free public libraries. To Carnegie this was practical philanthropism, not charity: ‘I choose free libraries as the best agencies for improving the masses of the people,’ he said, ‘because they only help those who help themselves. They never pauperise, a taste for reading drives out lower tastes.’

He continued to endow libraries across America and all over Britain and beyond: $500,000 in 1885 to Pittsburgh for a public library; $250,000 to Allegheny City for a music hall and library; $250,000 to Edinburgh for a free library. In total Carnegie funded some 3,000 libraries, more than 600 in Britain and Ireland, and nearly three times that number in the US.

Not bad for a boy from Fife.

Penny Dreadful to Thumb Novel

‘Make ’em laugh, make ’em cry, make ’em wait’

(Wilkie Collins)

Wander down any street in Japan, travel on public transport there, and you’ll notice something remarkable: The thumb tribe — oyayubizoku — are at work: Japanese teenagers typing constantly on their mobile phones, communicating in text and, most recently, reading and telling stories in the form of so-called thumb novels . Lurid romantic fictions are tapped out in instalments by novice authors and devoured by mostly young and female mobile-phone users.

It’s a form of writing which sits happily with the publishing phenomenon of serialized fiction, which, arguably, marked the beginning of society’s first mass popular culture. The popularity of the novel in instalments amongst the working classes went hand-in-hand with developments in printing and an increase in mass literacy rates in the nineteenth century. All the great Victorian novelists, including George Eliot, William Thackeray and Joseph Conrad, published their newest works of fiction in instalments, but the undoubted genius of the format was that prodigious wordsmith Charles Dickens.

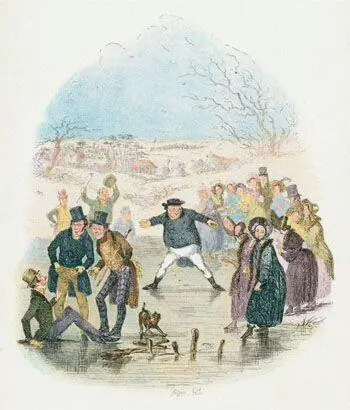

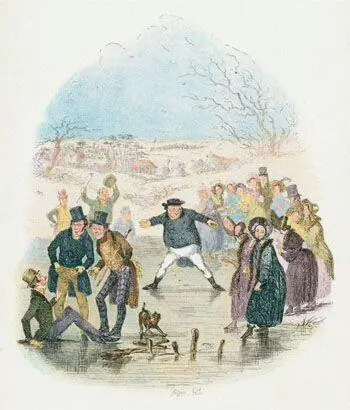

Most of Dickens’ working-class readers couldn’t afford the price of a full-length novel, so he published the bulk of his major novels in monthly or weekly instalments which could be bought for a shilling. Many of the instalments ended with a cliff-hanger, ensuring the sales of the next one. Sales of copies of his first serialized novel, The Pickwick Papers , in 1836 went from 1,000 for the first edition to 40,000 for the final instalment. Brimming with memorable characters, strong narrative, acute observation, comedy, villainy and tragedy — all the Dickens trademarks — The Pickwick Papers became one of the most successful novels of its time and thrust the twenty-four-year-old author into literary stardom.

Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers was serialized and each edition sold for just a shilling

Dickens’ writings appealed to people across the social spectrum, and due to the new technological advances in publishing and transport he could reach a reading public of unprecedented size. His serialized novels were so gripping, so entertaining, that when he published The Old Curiosity Shop in instalments between 1840 and 1841, weekly sales rose to 100,000. As it reached its climax — the death of Little Nell — Dickens was inundated with letters begging him not to kill her off. It’s said that when English ships docked in New York, crowds filled the piers, shouting ‘Is Little Nell dead?’ Nell’s death scene caused even grown men to cry. Dickens’ associate, the Scottish judge Lord Jeffrey, was apparently found openly weeping and confessed, ‘I’m a great goose to have given way so, but I couldn’t help it.’

Читать дальше