John Simpson first started working on the OED in 1976, in the pre-computer age; back then, the process of compiling the dictionary with the aid of millions of index cards hadn’t really changed since the nineteenth century, when it all began. Below his office is the archive room where some of the index cards from the first dictionary have been preserved: 700 boxes filled with neatly tied packets of dictionary quotation slips and a topslip with the definition — many of them in the tiny handwriting of the OED ’s extraordinary first editor, James Murray.

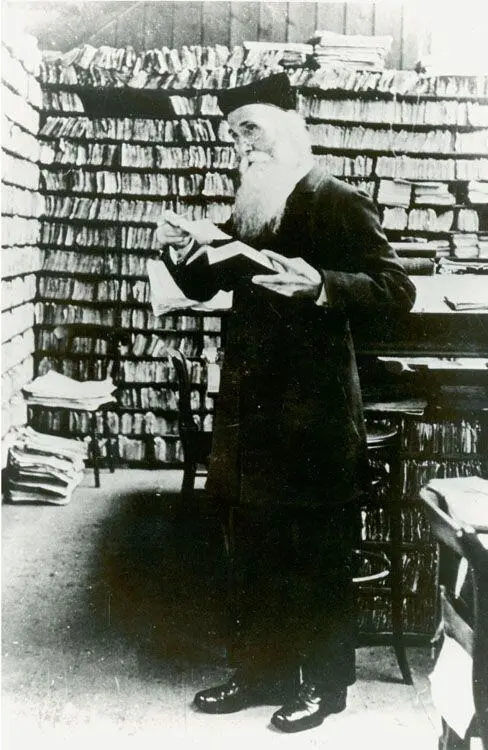

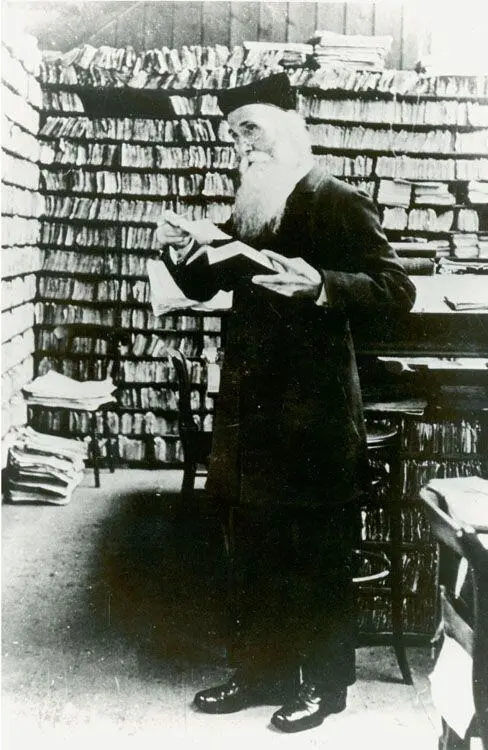

James Murray, the Oxford English Dictionary ’s first editor, surrounded by boxes of definitions

This white-bearded lexicographer gazes from photographs on the wall, a dead ringer for Professor Dumbledore. Murray was the Scottish schoolteacher and self-taught philologist (he claimed a working knowledge of twenty-five languages including Russian and Tongan) who was invited by the Philological Society of London in the late 1870s to realize their vision of a new dictionary to replace the existing outdated and incomplete dictionaries of Samuel Johnson and others.

The Oxford University Press was to publish it in instalments, and whereas Johnson’s dictionary had drawn heavily on a main group of literary sources — Shakespeare, Dryden, Milton, Addison, Bacon, Pope and the Bible — the new collection of words and meanings would be supported by evidence drawn from a myriad of works and sources. Murray thought that the task could be completed in ten years and at first planned to keep on his job as a teacher at Mill Hill School whilst editing the dictionary at home. Little did he realize the gargantuan task he faced, both in collecting the quotations and then filing and editing them.

In April 1879, a month after his appointment, an appeal went out ‘to the English speaking and English reading public’ for a thousand people to ‘read books and make extracts for The Philological Society’s New English Dictionary’. A list of books, starting with Caxton’s printed works, was included. All offers to help were to be addressed to ‘Dr Murray, Mill Hill, Middlesex, N.W.’

In preparation for the flood of responses, and to store the sacks of quotation slips already amassed, Murray built a corrugated iron shed in his front garden, jokingly called the scriptorium. After six years, when the dictionary had only reached A for Ant , Murray gave up his teaching job and moved his family to a bigger house in Oxford, building a larger version of the scriptorium in his back garden.

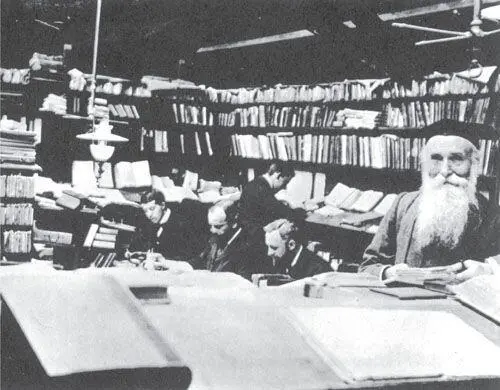

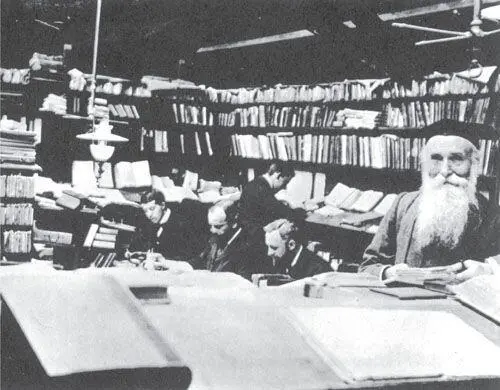

It’s here that the photographs of Murray, the white-bearded sorcerer of words, were taken. Perched on his head is the black cap in the style of his hero, the Protestant reformer John Knox, which he insisted on wearing to work every day. Surrounding him are shelves and pigeonholes bulging with millions of quotation slips illustrating the use of words to be defined in the dictionary. At one point these slips were arriving from volunteer readers at a rate of 1,000 a day; Murray even roped his eleven children into the work of sifting and alphabetizing them alongside his small team of assistants.

James Murray and his team of assistants in his specially built shed

One of Murray’s most prolific early contributors was an American surgeon by the name of Dr William Chester Minor. Over the years he and Murray corresponded regularly. Minor gave his address as Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire, so Murray must have known that he was connected to the Broadmoor Hospital for the Criminally Insane. But it wasn’t until 1891, when Murray visited Dr Minor, that he learned the full story. Minor, a surgeon in the Union army during the American Civil War, had been committed to Broadmoor in 1872 after shooting dead a stranger, George Merrett, in London.

Minor lived a fairly comfortable life at Broadmoor. He had two rooms — a bedroom and a dayroom — and a private income which allowed him to buy books and good food. He sent money to the widow of the murdered Merrett, and it’s said that the two got on so well that she visited him monthly, bringing him new supplies of books. In 1879, Minor heard about the appeal for readers for the new English dictionary and he set about the task which dominated most of the remainder of his life. Over the next twenty years, Minor supplied tens of thousands of quotations. James Murray described his contributions to the writing of the dictionary as ‘enormous’, acknowledging that, in a two-year period, Minor had sent in at least 12,000 quotations.

A typical submission from Minor to James Murray is his contribution to the verb to set : ‘a1548 Hall Chron., Hen. IV. (1550) 32b, Duryng whiche sickenes as Auctors write he caused his crowne to be set on the pillowe at his beddes heade’.

The two men became friends over the years, with Murray making frequent visits to the surgeon at Broadmoor. When Minor’s mental health deteriorated, Murray campaigned for his release, and in 1910, thirty-eight years after entering Broadmoor, Minor was allowed to return to America. He died in a hospital for the elderly insane in Connecticut ten years later.

Minor outlived his friend Professor Murray, who was still only at the letter T when he died in 1915, working on the word take . The ten-volume dictionary was finally completed in 1928, almost thirty years after Murray began it. The final letter to be completed was W , as the team working on XYZ had already finished. In the W team, by the way, working on waggle t o warlock , was one J. R. R. Tolkien.

Today, with a fully computerized, online OED , editor John Simpson and his team of lexicographers are coming face to face with the English language’s boundlessness. ‘It’s constantly moving,’ says John. ‘It’s fascinating.’ New words are coined one minute and spread like wildfire the next. As a result, the rate of change in language itself has switched into hyperdrive. A printed version — with a due date estimated some time in 2037 — will be so vast, so heavy and so expensive that it’s little wonder that the Oxford University Press may consider never printing the OED again.

The online dictionary’s advanced author quotations search is tempting for any prolific writer interested in discovering how often they have been cited as a source. Type in ‘S Fry’ and, as well as telling you it’s short for stir fry , the search engine throws up twenty-three words listed against the name, among them paramnesia, to pinken (taken from P. G. Wodehouse), ack-emma and pip-emma for a.m. and p.m. (Woodhouse again) and otherwhere (not a neologism — its first reference is in 1400!).

For a lover of words, John must have quite simply the best job in the world. Working with a living, moving stream of words, the whole of the English language his bailiwick. John is somewhat more restrained. ‘It’s rather nice,’ he murmurs.

As Stephen Fry exults, ‘There’s an excitement about the cries and whispers and the solaces and the seductions that are contained within the bound form of a single book. And when you have thousands together it’s as if all of human history, all of human hope is captured and is murmuring to you like sirens, pulling you in.’

Libraries are more than just buildings, just as books are more than just print and ink. As the poet and political theorist John Milton said, ‘Books are not absolutely dead things, they do contain a potency of life in them. He who destroys a book, kills reason itself.’ Perhaps that’s why tyrants everywhere have always attacked libraries before almost anything else. In the third century BC, the Chinese Emperor Shi Huangdi ordered that all literature, philosophy and poetry written before his dynasty should be destroyed. Books from the Persian library of Ctesiphon were thrown into the Euphrates in AD 651 on the order of Caliph Umar. And Mongol invaders in 1258 attacked Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, the single largest library in the world at the time, destroying some of the oldest books ever written. It was said that for six months the waters of the Tigris ran black with ink from the enormous quantities of books flung into the river.

Читать дальше