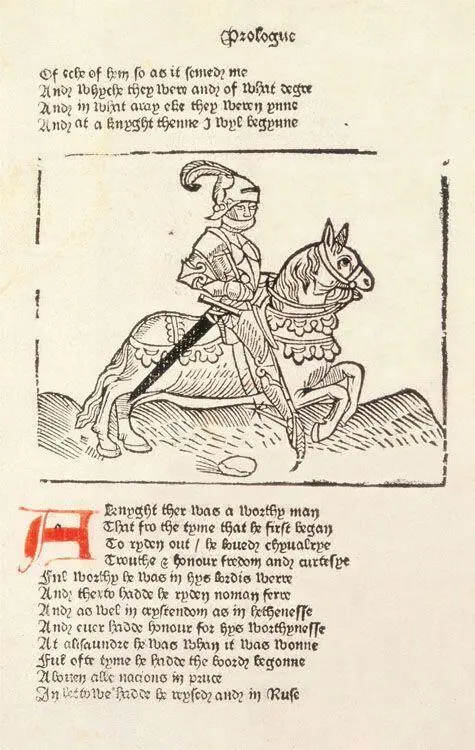

Prologue to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales , 1485

Diderot and the Encyclopédie

Printing didn’t just give rise to greater literacy; it was one of those inventions, like gunpowder and the compass, which changed the state and appearance of the world. With more books available to more people, reading went from being an exercise of the elite, to a far more accessible activity. And because more people could read more, it changed attitudes towards learning and knowledge. As printing spread, the costs decreased, and booksellers proliferated, especially in the big European capitals, like Paris and London. The printed word became the life blood of the age of reason and inquiry we call the Enlightenment.

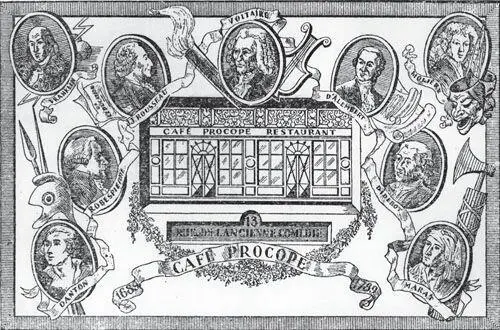

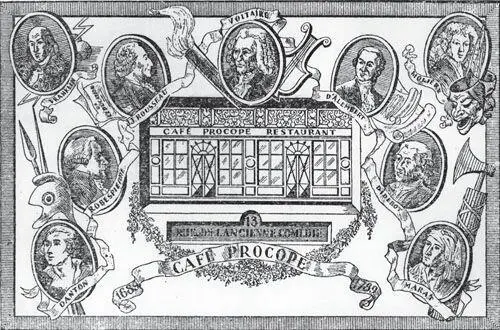

The booksellers of Paris have long been part of a kind of literary underworld, spreading subversive ideas by printed pamphlets, books, leaflets and newspapers. And in the eighteenth century the cafés, or coffee houses, were the places where all these ideas were discussed. In Paris and in London like-minded thinkers congregated to read, as well as learn from and to debate with each other. The Café Procope is one of the oldest and most famous, where writers, philosophers, intellectuals, politicians and anyone who liked an argument would hold court and exchange ideas and gossip. ‘There is an ebb and flow of all conditions of men, nobles and cooks, wits and sots, pell mell, all chattering in full chorus to their heart’s content,’ was how one contemporary writer described the scene. Voltaire used to go there and, so the story goes, get through forty cups of coffee a day, mixed with chocolate. Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Paul Jones, Jean-Jacques Rousseau — they were all players at the Procope.

This was café society at its most potent, a sort of borderless intellectual republic of letters and ideas and free thought where the driving forces of the Enlightenment — the critical questioning of traditional institutions, customs and morals, the central belief in rationality and science — had free rein. In a way, this period began the process that has ended with the internet and social networks.

The Café Procope in Paris, meeting place for revolutionary thinkers

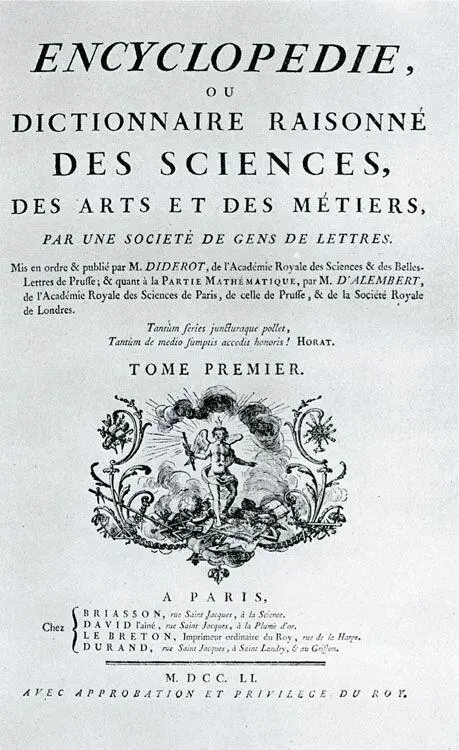

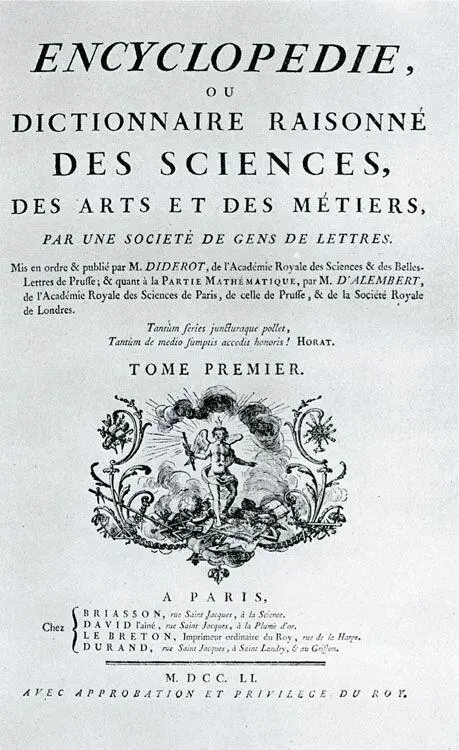

What better place, then, to find Dr Kate Tunstall, an Enlightenment scholar, to talk about the book that embodied the new way of thinking and the extraordinary man behind it — the Encyclopédie and its editor, Denis Diderot. The Encyclopédie — ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des sciences, des arts and des métiers (‘Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts and Crafts’) was originally commissioned as a translation into French of the Cyclopaedia of Ephraim Chambers, which first appeared in 1728, but in the hands of the polymath Denis Diderot it grew into something huge, radical and utterly contemporary.

‘Diderot knew English and he was also known to be subversive and, therefore, marketable,’ says Kate. The booksellers behind the project were businessmen as well as publishers, and they had an eye to a successful commercial enterprise. And if they were looking to make a splash with their main choice of editor, Diderot was the right man.

Denis Diderot was a novelist, playwright, art critic, man of science and philosopher — and the most talkative man of his generation, according to one contemporary. The Enlightenment was a time when science and reason began to challenge the authority of the Church, and Diderot worked under threat of exile during most of his life because of his controversial, subversive views. In fact, he landed in prison for three months not long before the first volume of the Encyclopédie came out in 1751. ‘We know he had these dinners at his home where he openly declared himself an atheist,’ says Kate, ‘and one of the reasons he was arrested, we think, is that his parish priest had been reporting on him to the police.’

The Encyclopédie publishers were extremely upset at Diderot’s imprisonment because they feared financial ruin. ‘So they wrote to the authorities,’ continues Kate, ‘saying, “Please let him out.” And one of the things they explain is that, if they had to bring all the manuscripts to Diderot in prison, even at this early stage, they would fill a whole room! So you have to imagine Diderot sort of surrounded by paper, trying to fit it all together.’

It’s a vivid image of just how massive an undertaking the Encyclopédie was. Diderot, and his co-editor d’Alembert (who left the project after a couple of years), commissioned essays and articles, not just on the academic and scientific knowledge of the day, but on the technologies, industries and trades of the working people. ‘An encyclopedia … should encompass not only the fields already covered by the academies, but each and every branch of human knowledge,’ Diderot wrote. And by doing so, he maintained, it would ‘change the way people think’.

And it would do it, too, by influencing opinion and thought, by challenging authority, introducing new ideas, looking at things differently. Diderot was clever, though, in suggesting radical ideas rather than headlining them. He used irony and strategies of subversion within the text. Articles say that they’re going to be about one thing, and then they turn out to be about something slightly different. Or they have cross-references to a directly opposing point of view. That was Diderot’s way of changing the normal way of thinking. So if you look up ‘cannibal’, for example, there’s a cross-reference to Eucharist and Communion — so he’s making a point about, or mocking the idea of, the eating of the body and blood of Christ in church. And there’s a streak of mischievous wit, too, in some of the entries where Diderot plays about with the notion of what should and shouldn’t be in an encyclopaedia, and what some people are expecting to find. Kate’s favourite one is ‘aguaxima’: some kind of plant found in Brazil. But Diderot’s entry (and we know it’s his because it’s preceded by an asterisk, which was his sign) is completely tongue-in-cheek. He has nothing interesting to tell about it, so he just mocks the convention of including it in an encyclopedia at all. This is plainly not the challenging and ground-breaking material he was interested in.

Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie , 1751

Aguaxima, a plant growing in Brazil and on the islands of South America. This is all that we are told about it; and I would like to know for whom such descriptions are made. It cannot be for the natives of the countries concerned, who are likely to know more about the aguaxima than is contained in this description, and who do not need to learn that the aguaxima grows in their country. It is as if you said to a Frenchman that the pear tree is a tree that grows in France, in Germany, etc. It is not meant for us either, for what do we care that there is a tree in Brazil named aguaxima, if all we know about it is its name? What is the point of giving the name? It leaves the ignorant just as they were and teaches the rest of us nothing. If all the same I mention this plant here, along with several others that are described just as poorly, then it is out of consideration for certain readers who prefer to find nothing in a dictionary article or even to find something stupid than to find no article at all.

Читать дальше