And yet we don’t really know very much about Gutenberg himself. He was born in the German town of Mainz in 1400 and died, a poor man, sixty-eight years later. In between, he sort of flitted about, disappearing for periods, re-emerging somewhere else, always working on something, always short of money, frequently involved in some dispute or quarrel. At one stage he was sued for debt by the man who financed his printing press, and he ended up losing the press in lieu of payment. We don’t know whether he was married, or whether he had any children, but his achievements were recognized at the end of his life when he was given the title Hofmann (gentleman of the court), an annual stipend, 2,180 litres of grain and 2,000 litres of wine tax-free. He was buried in the Franciscan church at Mainz, but the church and the cemetery were later destroyed, and Gutenberg’s grave is now lost.

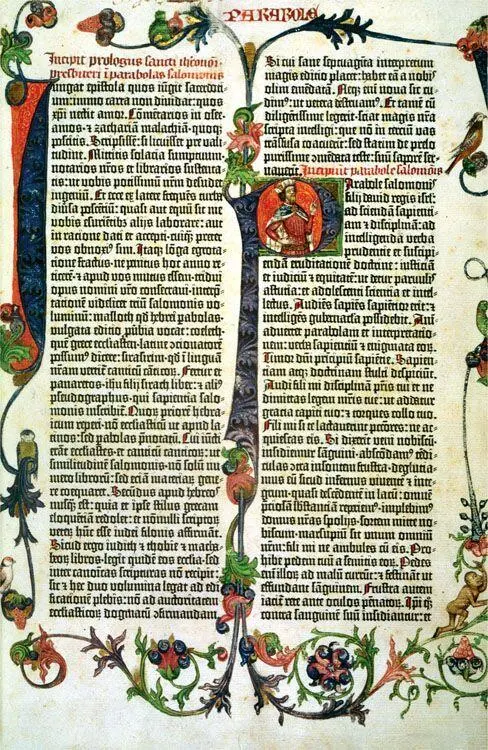

The first real book to be printed using the new techniques Gutenberg developed in the 1450s was the Gutenberg Bible, also known as the forty-two-line Bible. No one knows exactly how many copies he printed, but the best guess is around 180–145 on paper and the rest on the more luxurious and expensive vellum. Only forty-eight copies survive, not all of them complete, and scholars consider them to be among the most valuable books in the world. The Bible is a thing of beauty, printed in Vulgate Latin on hand-made, fine-quality paper from Italy in Blackletter font on a page design that was deliberately created to look like an illustrated manuscript. Each copy was sold in folded sheets and was later bound and decorated according to the wishes of its owner. They cost much less than a handwritten Bible, but at least some copies are known to have sold for 30 florins, a price beyond most students, priests or other people of ordinary income. Probably most of them were sold to monasteries, universities and particularly wealthy individuals.

The price of books began to fall as the technology of printing improved and the number of printing presses all over Europe increased. But although the process of printing was new, in the early years the printer was in direct competition with the scribe and he wanted to make books, like the Gutenberg bible, that were as luxurious and beautiful as the handwritten ones.

So printers left large areas of the page blank so that an illuminator could decorate the text afterwards and create the same ornate, elaborate capital letters and richly illuminated patterns as the manuscripts. The same Gothic characters were reproduced in the new fonts, and the printer would even join up some of the letters so that they looked as if they’d been written by a quill pen. It was as if the printer was saying: ‘Look, this is new and it’s the future — but it’s just as splendid and well produced as what you’re used to.’

Gutenberg’s Bible with hand-illuminated letters to help ease the transition to print

The nineteenth-century writer, historian and social commentator Thomas Carlyle is pretty good for a quote on most things, and his comment in Sartor Resartus (1833) on the invention of the printing press has all the drama and flair you’d expect: ‘He who first shortened the labor of copyists by device of movable types was disbanding hired armies, and cashiering most kings and senates, and creating a whole new democratic world: he had invented the art of printing.’

It’s the creation of a new ‘democratic world’ of the free circulation of knowledge and learning that’s at the heart of the printing revolution. As printing spread, it created a wider literate reading public, and it vastly increased the range of books and subject matter. The Church had dominated book production up to then, authorizing what was to be copied and controlling access to learning. But now, more secular books began to be printed, and religious books, bibles (like the pocket versions by the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius) and tracts could be printed in great numbers and widely disseminated. Now people could read and decide for themselves.

This was crucial to the success of the Reformation in Europe. Martin Luther was armed not just with radical ideas, but with a printing press. It’s easy to burn heretical texts which have a few hundred manuscripts in circulation; but what does the Church do when thousands of texts can be sprayed around quickly and at a fraction of the cost? William Tyndale, the scholar and translator, found out when he challenged the authority of the Roman Catholic Church and the English Church and state by translating the Bible into English. Copies of his Bible were secretly published and passed around Europe, and he was tried for heresy and burned at the stake in 1536. The French humanist scholar and printer Etienne Dolet was twice condemned to death and twice pardoned for his printing of classical works and authors like Rabelais and Calvin. He was eventually burned at the stake for heresy in Paris in 1546. He’s often called the first martyr of the Renaissance. Printing spread learning and enabled the radicalism of the Reformation and the humanist ideas of the Renaissance to percolate through all levels of society. In Britain it also had a profound effect on the written language.

Geoffrey Chaucer was the first English writer to be set in print, though, as he died just around the time that Gutenberg was born, he missed the print revolution. But he certainly made it clear that he was pretty fed up with the sloppiness of the scribes who copied out his works for readers. In fact, in one of his great poems ‘Troilus and Criseyde’, there’s a bit at the end when he writes a little verse to the reader which shows his anxiety about the lack of standardization in written and spoken English. He basically asks that his poem isn’t too badly mangled by the copyist: ‘for there is so great diversity in English and in writing of our tongue so pray I God that none miswrite thee little book. Neither miss meter for default of tongue and where so thou be or else sung that that thou be understonged. God I beseech.’ In other words he hoped that people would find some way of spelling all the different words at least in such a manner that it was generally understood by those who were going to read it.

And that’s precisely what printing allowed. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales was the first book by an English author that the printer William Caxton published in England. Caxton started printing at a time when the English language was going through a period of massive upheaval. It was changing from the Middle English of Chaucer to the Modern English we speak today — a process that’s called the Great Vowel Shift. The ‘continental’ pronunciation of sounds based on Latin and Italian gave way to more regional lilts at about the same time written English was catching on through the printing press.

This was a time when the English language was incredibly diverse. Dialects of different regions had different words for the same thing, and as for spellings of the same words, well, there were over twenty different spellings just for the word might ! In order to sell as many books as possible, Caxton needed a linguistic norm for the vernacular. He needed what Chaucer was looking for in his complaint at the end of ‘Troilus and Crisedye’ — a standardized, consistent spelling that could be understood by everyone. So Caxton printed the dialect of London and the South-east Midlands (though he dumped his Kentish eyren in favour of northern egges ). Through the medium of print, Caxton made people across the country familiar with I rather than ich and home rather than hame . On the one hand he preserved old spellings that no longer matched pronunciations; on the other hand he started to modernize prose. Printing added an element of linguistic stability to literature. No doubt Chaucer would have approved.

Читать дальше