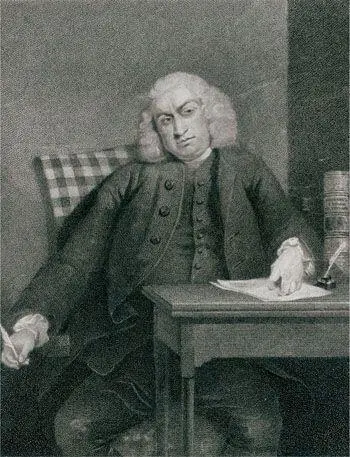

Dr Samuel Johnson assembled the first major English-language dictionary

That was another discovery he made early on in his work: he was not content to produce a dictionary that was prescriptive, i.e. which set out how the language should be. He wanted it to be descriptive — to be faithful to the richness and flexibility of English as it was used. When he was drawing up his plan at the start, he thought that a word might have, at the most, seven or eight different meanings: in the event, he found words with twice or even three times as many subtle differences of usage. For the word put , he included 134 different meanings, among them to ‘lay’ or ‘place’; to ‘repose’; to ‘urge’; to ‘state’; to ‘unite’; to ‘propose’; to ‘form’; to ‘regulate’ — the list goes on and on. Time had twenty definitions and fourteen illustrative quotations; turn had sixteen definitions and fifteen examples.

The point was, here was language sorted and illustrated by the standards of literature — and for literature read ‘how the language was actually being used, in all its invention and shades and evolutions of meaning’ — not language as it ought to be, or language bound for ever to some elegant, academic fixed standard. In his preface to the book Johnson described the ‘energetic’ unruliness of the English tongue. ‘Wherever I turned my view,’ he wrote, ‘there was perplexity to be disentangled, and confusion to be regulated.’ His original aim, he said, was ‘to refine our language to grammatical purity’. But it was his genius to recognize that language is impossible to set in stone, because its nature is to change and evolve. And so, he said, he realized his role was to record the language of the day, rather than to form it. It was an approach which would have a lasting influence on the future writing of dictionaries.

Johnson didn’t work entirely alone. He employed a handful of secretaries and assistants — all but one hailed originally from Scotland — to collate the thousands of passages and words he marked up in his reading. He turned the top floor of his house into a study and his atticful of Scotsmen laboured through the mind-numbing process of cutting up the definitions and quotations into little slips, ordering and arranging them, copying them into notebooks and adapting the process as the dictionary grew ever larger. Imagine the energy and dedication, the sheer concentration required to continue this painstaking, repetitive, exhausting work day after day for nine years. No wonder Johnson was thoroughly fed up — even depressed, probably — by the end. One of the illustrations he used for the word ‘dull’ he made up himself: ‘To make dictionaries is dull work’, and another famous one is his definition of a ‘lexicographer’: ‘a harmless drudge’. And in the preface he doesn’t pretend that the process has been anything other than long, hard and draining: ‘I have protracted my work,‘ he writes, ‘till most of those whom I wished to please, have sunk into the grave, and success and miscarriage are empty sounds.’

However hard it was to compile, it’s a brilliant, endlessly fascinating book to dip into. There’s such flair and wit, such colour and life in it. There is an ease and facility in Johnson’s writing, an economical elegance of some of his definitions. Take dotard :‘one whose age has impaired his intellect’; embryo : ‘the offspring yet unfinished in the womb’; envy : ‘to repine at the happiness of others’, or the words which show an earlier, more literal meaning, like eavesdropper : ‘a listener under windows’; or jogger : ‘one who moves heavily and dully’. And then there are the curmudgeonly, witty definitions which are one part linguistic definition and three parts personal prejudice. The pleasure is not in the accuracy or strict factual truth of the definition, but in the amusement and entertainment it provides, like the famous oats : ‘a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people’; or excise : ‘a hateful tax levied upon commodities and adjudged not by the common judges of property but wretches hired by those to whom excise is paid’.

When the Dictionary was published in 1755, two volumes’ worth and a total of 2,300 pages, it was generally well received. Johnson was certainly criticized for various omissions and errors, like there being no entry for a simple word like irritable , and leeward and windward being given the same definition. The etymology was sometimes wayward — the historian Thomas Macaulay called Johnson ‘a wretched etymologist’ — and one philologist declared that the grammatical and historical parts of the Dictionary were ‘most truly contemptible performances’. And, of course, what makes the Dictionary fascinating and delightful and creative — the fact that it’s the vision and execution of one man — is exactly what makes it flawed.

But the magnitude and breadth and flair of the Dictionary are undeniable. It is an astonishing work of individual scholarship and genius, the influence of which has stretched across the world and even further across the centuries. Noah Webster, the editor of the American Webster’s Dictionary , disliked many aspects of Johnson’s Dictionary, but he, too, liberally helped himself to verbatim chunks of it for his new work.

Perhaps the most curious footprint left by Johnson’s Dictionary is to be found, of all places, in the US Constitution. The Dictionary’s biographer, Henry Hitchings, tells us that American lawyers still refer to Johnson in questions of interpretation because, when the Constitution was originally drawn up, in the late 1780s, it was his Dictionary which was the prevailing authority on the English language. He cites an example from 2000, when American lawyers were debating whether US airstrikes against Yugoslavia violated the Constitutional principle that Congress alone can declare war. One of the central issues was: what was the authentic eighteenth-century meaning of declare : if you declared war, did it mean actual military engagement, or was it simply an acknowledgement of the necessary prior conditions for conflict? They turned to Johnson for guidance as to what the words of the Constitution meant. That would no doubt have given Dr Johnson a good deal of satisfaction.

Not Just a Dictionary but a National Institution

The story goes that the first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary kept a copy of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary open on his desk as he worked, marking all his definitions he included in the new tome with a ‘J’.

The OED , as it’s more commonly known, is considered to be the authority on the English language. Quite simply, it’s one of the wonders of the world of words. Its second edition, printed in 1989, is the definitive guide to the meaning, history and pronunciation of over half a million words, past and present. These words make up 21,730 pages, bound in twenty dark Oxford-blue volumes, and take up four feet of shelf space. And the shelves themselves need to be pretty robust, given that the OED weighs almost 140 pounds.

The OED ’s policy is to record a word’s most-known usages and variants in all varieties of English. It’s a constantly evolving process, as new words enter our language all the time — and for this, the online version is ideal.

The OED ’s chief editor, John Simpson, was in charge of bringing the entire second edition of the dictionary into the internet age in 2000. John is now managing the first complete revision of the twenty-volume dictionary since it was originally published in 1933. His team started work at the letter M and they release updated sections of words every three months; in March 2011 they’d reached Ryvita . Computers and the internet may make revision physically easier and quicker, but up-to-the-minute access to rapidly expanding historical databases — from eighteenth-century farming manuals to twenty-first-century rap lyrics — means this is still a massive archaeological dig into the English language.

Читать дальше