And it’s not just in ancient times that such wanton acts of destruction were carried out. The twentieth century saw more book burning than any other time in human history — in Nazi Germany, in Bosnia, in Afghanistan

The story of libraries is as old as the story of writing itself, for wherever and whenever we have committed knowledge to clay tablet or papyrus, bamboo or palm leaf, parchment or paper, ways of keeping that information safe and accessible have had to be found. The first libraries were mostly archive collections of commercial transactions or inventories — like the Sumerian temple rooms full of clay tablets in cuneiform or the papyrus records of the governments of ancient Egyptian cities. An archaeological dig in the ruins of a palace in Ebla in Syria uncovered shelves of clay tablets dating back to 2500 BC. The tablets — as many as 1,800 in complete form and thousands more in fragments — were inscribed with lists of the city’s imports and exports, royal edicts, religious rituals and hymns and proverbs. They had been stored upright on shelves, positioned so that the first words of each tablet could be seen easily, and separated from each other by pieces of baked clay. Civilization’s first library stack, perhaps.

The flourishing of literacy and intellectual life in ancient Greece saw the extension of libraries into public life. An author would write his book on nature or astronomy on a parchment or papyrus scroll, take it to be copied (by hand of course) at a copy shop and then arrange for those copies to be sold via book dealers. Some copies were of a higher standard than others so a decree in Athens called for a repository of ‘trustworthy’ copies. By the time of the Romans, collections of scrolls were available in the dry sections of the public baths for bathers to peruse.

The most prevalent collection of writings, however, were private ones. In the fourth century BC, the Greek philosopher Aristotle amassed a huge personal library. According to the historian and geographer Strabo, writing 300 years later, he ‘was the first to have put together a collection of books and to have taught the kings in Egypt how to arrange a library’.

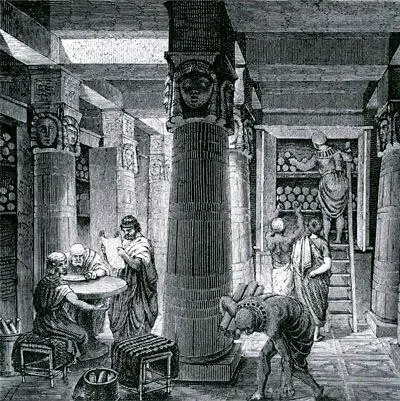

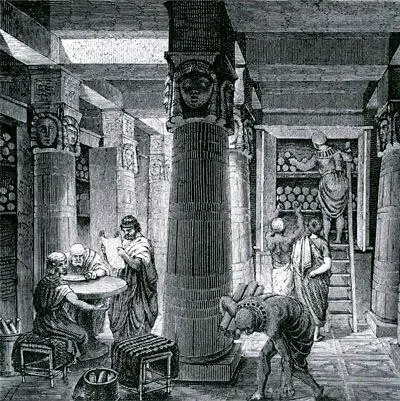

That library was the wondrous Library of Alexandria, built around 300 BC by Egypt’s Ptolemy I. It was apparently the brainchild of one of Aristotle’s disciples, Demetrius, who inspired Ptolemy with the vision of a public library open to scholars and holding copies of every book in the world. There are a number of colourful stories about how Ptolemys I, II and III went about amassing the ancient world’s greatest collection of books. Ptolemy I sent letters to kings and governors, begging them to send back to his library all the works they could get their hands on. Ptolemy III is reputed to have ordered every visitor to the city to hand over all the books and scrolls in their possession. These were then quickly copied by library scribes and handed back to the traveller; the originals were kept for the library. Legend has it that Mark Antony gave Cleopatra over 200,000 scrolls for the library as a wedding gift, ‘borrowed’ from the rival ancient Greek Library of Pergamon.

At its peak the Library of Alexandria stored three-quarters of a million scrolls

At its peak the library held perhaps three-quarters of a million scrolls, many of them different versions of the same text. The papyrus and leather scrolls, with wooden identity tags attached, were kept in a honeycomb of pigeonholes inside ten great Halls dedicated to different areas of learning — mathematics, astronomy, physics, natural sciences and so on.

During the second century BC, people in the Mediterranean region began using parchment, a much more expensive alternative to papyrus. One theory is that the Library of Alexandria was using so much papyrus that Egypt had very little left to export. Another suggestion is that rivalry between the two Libraries of Alexandria and Pergamon was so intense that Ptolomy V tried to cut off the supply of books to the Greek rival by banning the export of papyrus.

Whatever the reason, the shortage of papyrus meant that the library at Pergamon was forced to rely on parchment instead. Indeed parchment — pergamenum in Latin — derives its name from the city. It took several centuries for it to develop into a viable alternative to papyrus and become the standard writing material for medieval manuscripts. Alexandria’s library lasted for around five centuries, until fires and civil war reduced and destroyed the vast collection.

The spread of Christianity and monasticism was a vital ingredient in the growth of libraries. The monasteries became the great centres of copying and preserving of codex manuscripts which had now replaced the scroll. The first Benedictine monastery, set up in Montecassino around AD 529, had a rule for monks which mandated: ‘During Lent … let them receive a book apiece from the library and read it straight through.’ Copying by hand was a labour-intensive, expensive business, and the manuscripts were prized possessions. Books were often chained to lecterns or shelves to prevent theft. Despite this, monasteries began lending volumes to each other — the first inter-library loaning system. It was these manuscripts — copied, sold or filched — which formed the core of the libraries of the Middle Ages.

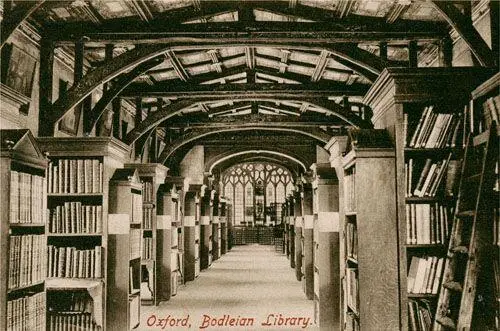

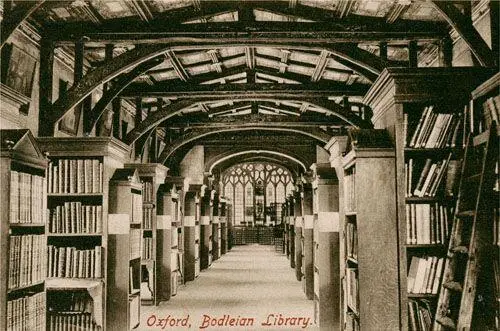

The Renaissance saw a new golden age of libraries as the aristocrats of Europe vied with each other as patrons of learning and the arts by amassing large private collections of early manuscripts. The library of the Medici family of Florence was so enormous that they commissioned Michelangelo in 1523 to build the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (The Laurentian Library) to house it. This period also saw the founding and growth of universities — and with it the university library. Another patron of the arts, Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, youngest brother of Henry V, donated his collection of 280 manuscripts to Oxford University in the early 1400s. ‘Duke Humphrey’s Library’ became the foundation of Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

The Bodleian Library at Oxford University is a network of thirty libraries, linked by underground tunnels

The Bodleian is one of the oldest libraries in the world, home to over 11 million books, maps and documents, a glorious institution, described by Yeats as the most beautiful building in the world (although he died before the building of the New Bodleian, which travel writer Jan Morris described as looking like a municipal swimming bath). For over 400 years scholars have had to swear a solemn oath on joining the library: ‘I hereby undertake not to remove from the Library, or to mark, deface, or injure in any way, any volume, document, or other object belonging to it or in its custody; nor to bring into the Library or kindle therein any fire or flame, and not to smoke in the Library; and I promise to obey all rules of the Library.’ Until the nineteenth century the oath would have been in Latin, but today one can choose from over 200 languages, from Maori and Manx to Celtic and Yiddish.

The line in the oath promising not to ‘kindle therein any fire or flame’ is a heartfelt one. Over the whole history of librarianship hangs the spectre of the burning of the Library of Alexandria, the greatest library of the ancient world. The ban on fire meant that the Bodleian was entirely unheated until 1845 and lacked artificial light until 1929. This kept opening hours rather short — as little as five hours a day during the darkness of winter.

Читать дальше