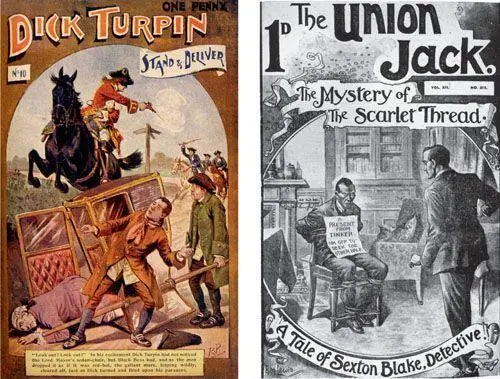

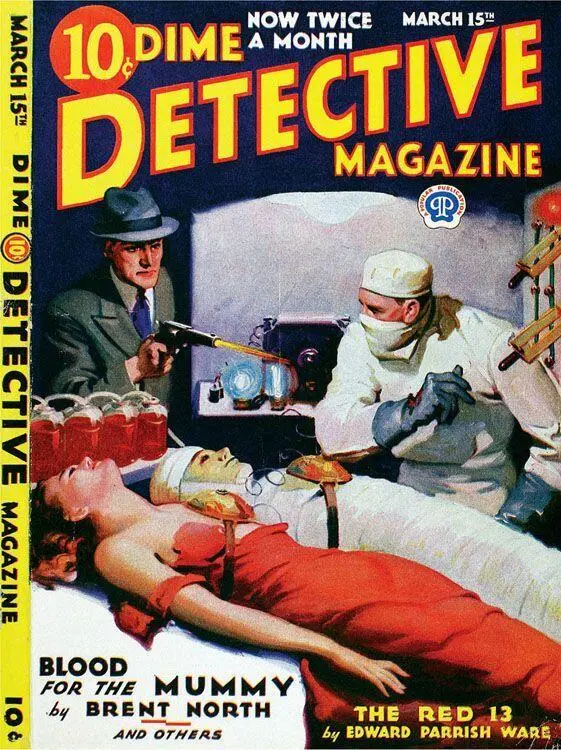

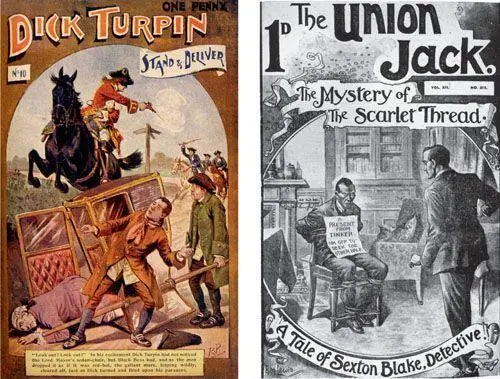

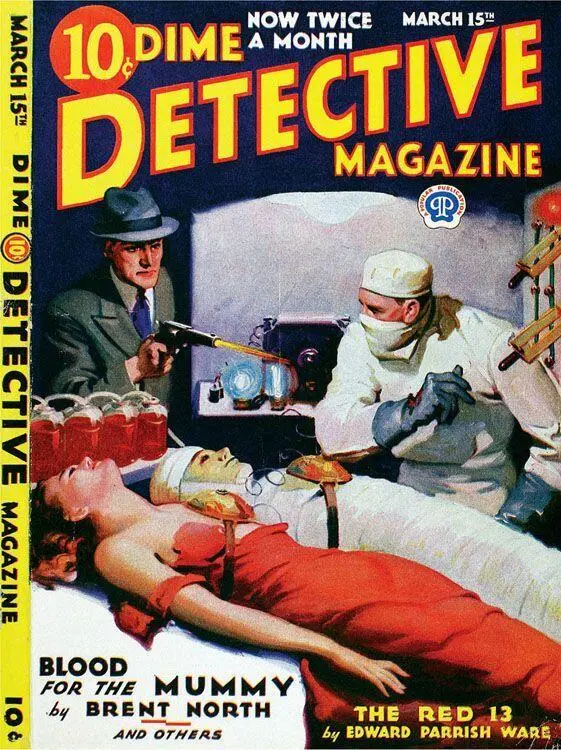

Penny dreadful stories were full of violence, gore and crime

Cheaper alternatives to the serial story began to be published in England around the same time Dickens was writing. The ‘penny dreadful’, or ‘penny blood’ or even ‘penny awful’ were serialized stories of sensational fiction, full of violence, gore, crime and horror, vampires, monsters and ladies in distress. The infamous Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber, made his literary debut in a penny dreadful serial called The String of Pearls: A Romance in 1846. Printed on eight pages of cheap paper and sold for a penny, the bloods were aimed at working-class adults, although eventually the readership became almost exclusively boys.

The dime novel was the American equivalent to the penny dreadful

The dime novel was the penny dreadful’s equivalent in the United States. The adventures of the American frontier characters such as Calamity Jane, Deadwood Dick and Wild Bill Hickok were the precursors of the first Western novels. The penny dreadfuls were formulaic and lurid, churned out by a string of mostly hack writers — what we might call pulp fiction today — but they offered a kind of written storytelling with a deep, widespread appeal. English writer G. K. Chesterton explained the attraction: ‘My taste is for the sensational novel, the detective story, the story about death, robbery and secret societies; a taste which I share in common with the bulk at least of the male population of this world.’

If the serialized novels of Dickens and the penny dreadfuls are the television of the nineteenth century, then what are we to make of the latest innovation in novel writing of the twentieth-first century?

Take a subway in any Japanese city and you’ll notice most of the young people glued to their mobile phones. They’re not making phone calls — Japanese etiquette frowns upon talking on public transport; they may be text messaging; but an awful lot of them will be using their flip-top mobiles to compose, share or read a new literary art form — the keitai shousetsu , or mobile-phone novel. In a country where an entire generation has grown up using mobile phones to communicate, watch TV and films, shop and surf the internet, writing thumb novels on the keypad is the obvious next step. Just as Dickens published his novels in instalments, so the thumb novel chapters, often only 100 words long, are sent directly to the reader one by one. They’re downloaded from mobile-phone novel sites, the largest of which, Maho i-Land, has 6 million members and more than a million titles. The stories are mostly romantic fiction with racy storylines involving rape, pregnancy and, of course, love. The thumb novels are often in diary or confessional form, heavy on dialogue and short paragraphs and liberally sprinkled with slang and emoticons. They tend to be written by novices and read by teenage girls and young women — although the first one of its kind was actually thumbed by ‘Yoshi’, a Tokyo man in his mid-thirties. ‘Yoshi’ (thumb novelists nearly always use pseudonyms) set up a website in 2000 and began posting instalments of his novel Deep Love , a lurid tale of prostitution, Aids and suicide. It was so popular that it was published in book form, selling 2.6 million copies; a spin-off TV series, manga and movie have followed.

One of the most famous thumb novelists is an eighty-nine-year-old Buddhist nun called Jakucho Setouchi. She’s something of a national treasure in Japan, famed for her translation of what’s thought to be the world’s first novel — the 1,000-year-old The Tale of Genji. Setouchi was appearing as a judge at the annual Keita Novel Awards when she suddenly made an announcement. For the last few months, she said, she had been posting a thumb novel called Tomorrow’s Rainbow under the pen-name ‘Purple’. Setouchi explained that she’d tried to write her simple love story on her mobile phone but found the thumbing too difficult. In the end she used paper and a fountain pen and sent Tomorrow’s Rainbow to her publisher for conversion into text.

‘I’m an author,’ she told her audience of thumb novelists. ‘When you finish a novel, to sell tens of thousands would be a tough thing for us, but I see you selling millions. I must confess that I was a bit jealous in the beginning.’ Many of the popular online novels are published in print, in the first half of 2007, five of the novels in Japan’s bestseller list started as thumb novels. The novels are not great literary works. They lack scene setting or character development. Yet, however crude, the thumb novel genre has encouraged people in their tens of thousands to tell stories, and millions of others to read them. That’s something Dickens himself would have applauded.

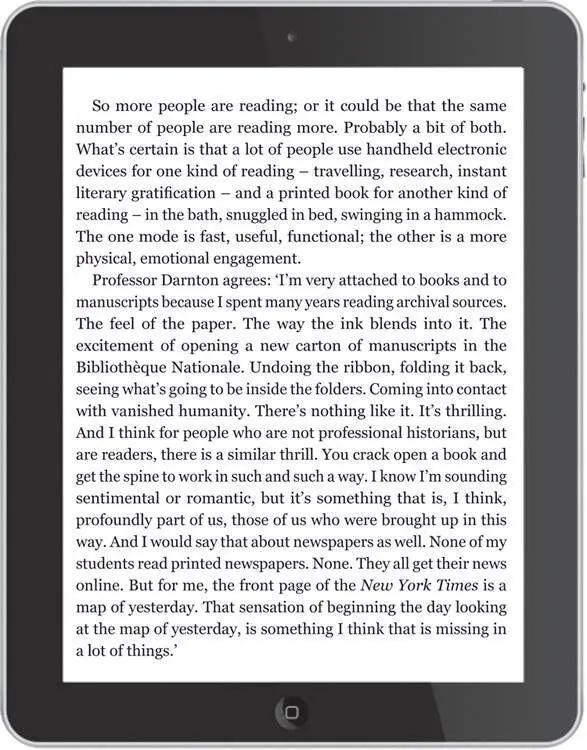

There’s a right royal battle of words raging over the future of the book — or more specifically, the future of the printed book. For, contrary to the doomsayers who have warned of the death of reading, people are in fact reading in increasing numbers; just in different ways. The digital revolution has brought us the e-book, the electronic book, and many lovers of the printed word aren’t happy. The American novelist the late John Updike was addressing a gathering of booksellers about the future of the printed book. ‘The book revolution,’ he told them, ‘which from the Renaissance on taught men and women to cherish and cultivate their individuality, threatens to end in a sparkling pod of snippets.’ Updike was bemoaning the tidal wave of unedited, often inaccurate, mass of information on the internet. ‘Books traditionally have edges,’ he said and concluded with a bibliophile’s call to arms. ‘So, booksellers, defend your lonely forts. Keep your edges dry. Your edges are our edges. For some of us, books are intrinsic to our human identity.’

Updike’s impassioned plea was met with an equally emotional response from e-book lovers. ‘Print is where words go to die,’ wrote one.

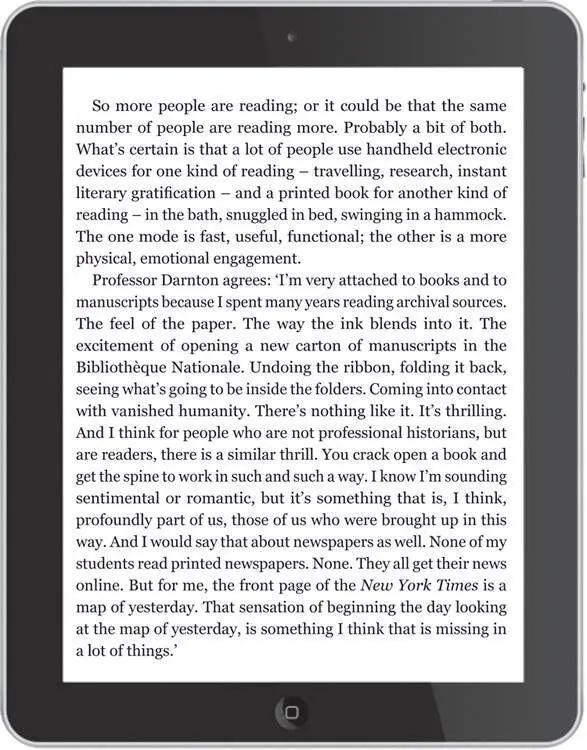

Professor Robert Darnton, a leading scholar in the history of the book and director of the Harvard University Library, insists that the book is very much alive, and the statistics seem to prove it. Each year more books are produced than the previous year. There was a dip during the recession, but next year, he says, 1 million new titles will be produced worldwide. And yet, the era of the book as the unrivalled source and vehicle for knowledge is undoubtedly coming to an end. We’re living in a time of transition in which the two media co-exist. It is, says Professor Darnton, a most exciting time.

‘One thing we’ve learned in the history of books is that one medium does not displace another. So the radio did not displace the newspaper. And television did not kill the radio. And the internet did not destroy television, and so on. So I think actually what’s happening now is that the electronic means of communication, all kinds of handheld devices on which people read books, are actually increasing the sales of ordinary printed books.’

Attachment to the printed book is not just the preserve of an older generation. According to one survey, 43 per cent of French students who were asked why they didn’t use e-books said they missed the book smell. There’s even a jokey aerosol ‘e-book enhancer’ called ‘Smell of Books’ on the market, promising to ‘bring back that real book smell you miss so much’.

Читать дальше