Language is our supreme evolutionary achievement, and this chapter is about how we can use it to sublime effect. We save our best words for our most complex thoughts, our attempts to win a sexual mate, deal with the inevitability of our own death or to persuade someone to do something they don’t want to do. It’s where language blooms in resplendent fashion. That doesn’t mean it has to be florid; it can have the simplicity of a haiku. Three hundred years ago, Alexander Pope wrote: ‘True Wit is Nature to advantage dress’d, What oft was thought but n’er so well expressed.’

A manual on how to hunt, plough, build a house, fight a war or paddle a boat can get by with pretty basic language. But courtship won’t go far if you say simply, ‘You look nice, let’s have sex.’ The same goes for death: ‘What, old dad dead?’ is a great line from The Revenger’s Tragedy , but mainly for dramatic impact. Hamlet’s ‘Oh that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw and resolve into a dew!’ certainly has more eloquence to it. Is it better? Well, that’s very subjective, and we all have our favourites, be they poems, songs, plays, novels or the speeches of a gifted orator.

The acme of language is literature; it defines our species, gives us voice, personality and history. Quite simply, it tells our story.

Essentially, what we like as a species across all cultures and throughout our history is a good story, well told: as Joyce would have it, the right words in the right order. We return first to that village in Turkanaland in north-east Kenya we visited earlier in the book, for the Turkana can tell us something about the beginnings of storytelling.

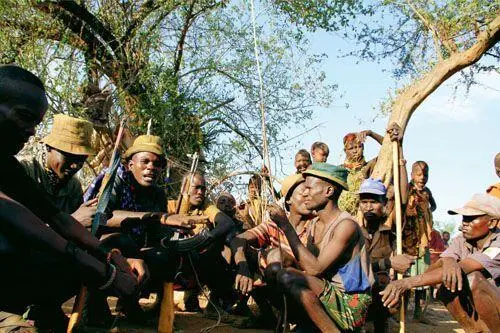

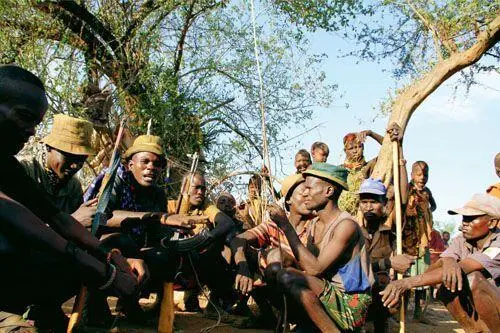

The village is about ten miles from the Sudan border. The Toposa, mortal enemies of the Turkana, live on the other side. The Toposa are as obsessed with cattle raiding as the Turkana, and for the young men of both tribes the raids are a way of life: ritually important and essential as a means of getting cattle to pay the bride price, so they can get married. It’s also tremendously exciting. Sometimes as many as a hundred heavily armed Toposa will cross the border and launch attacks. Up until thirty years ago both Toposa and Turkana relied mainly on ancient muskets, Enfields and spears, but now Kalashnikovs have replaced them. There is not a single spear to be seen, and even young boys of fourteen have an automatic rifle slung casually over their shoulders. As the day wears on the warriors start to drink their millet beer. Drunkenness and guns are never a good combination.

Turkana warriors keeping their traditions alive

But what the alcohol does is lower the inhibitions of the young warriors, and they start to tell stories of their escapades against the Toposa. Soon a crowd gathers and, emboldened by their audience, the young men launch into a full re-enactment of their latest raid. Miming their ambush of the Toposa warriors, they tell the story of capturing a hundred head of cattle, losing a couple of their men in a firefight and then the Toposa taking back some of their cattle only to be re-ambushed. The crowd love it, as do the warriors. This act of mimesis, miming out their story — with a few embellishments — goes to the heart of storytelling. There’s also a plot, action, humour (one of the men got shot in the buttocks — very Forrest Gump) and resolution.

The story is an improvised bit of drama without any religious or moral undertones. It’s a bit like an action buddy movie — a platoon of warriors on a dangerous mission meets with adversity, overcomes it; some are wounded, but the end is a happy one because the warriors return home victorious.

The Turkana have other stories, many of them traditional myths which attempt to answer the major themes of their lives. They do have a creator figure, Akuj, and there are many stories in which he is the protagonist. Most involve rain, which is the life-or-death commodity for the Turkana. These stories, like the Judaeo-Christian Bible, try to reconcile the big issues that trouble the Turkana. In the harsh environment where they live, the Turkana believe that the unreliability of the rains which cause drought, famine and death can be alleviated by the intercession of Akuj, the bringer of rain.

Storytelling is as old as language and is rooted in our life as a social animal. It is a universal across all cultures throughout history. When the Turkana tell a story they do more than just entertain the community, they bind it together in a communal ritual. This ritual (and it’s not so different from being read a Harry Potter book, or going to the cinema to see Avatar or watching a performance of Hamlet ) illustrates two of our most important traits: our ability to create imaginary worlds — fantasy — and our capacity to empathize. Empathy allows us to reach out to others and understand another’s emotions and needs whilst fantasy allows us to postulate alternatives and imagine new ways of seeing reality. Both are at the heart of good storytelling. But what could be the evolutionary advantage of being so prone to fantasy?

‘One might have expected natural selection to have weeded out any inclination to engage in imaginary worlds rather than the real one,’ says linguist Steven Pinker, but he thinks stories are in fact an important tool for learning and for developing relationships with others in one’s social group. And most scientists agree: stories have such a powerful and universal appeal that the neurological roots of both telling tales and enjoying them are probably tied to crucial parts of our social cognition. Pinker’s hypothesis is that as our ancestors evolved to live in groups, so they had to make sense of increasingly complex social relationships. Living communally requires knowing who your group members are and what they are doing and if possible what they are feeling and thinking. Storytelling is the perfect way to spread such information.

Storytelling is at the heart of the indigenous people of Australia. There were over 400 distinct Aboriginal clans when the first British settlers arrived in Australia, and each of them had their own body of stories that describe and link the eternal mythical world of what they call the ‘Dreaming’ with the everyday world of living. The stories are called ‘Songlines’.

It’s almost impossible for a non-Aborigine to understand the idea of the Dreaming which underlies the Songlines. The Dreaming is an English word that attempts to describe the entire mystical and ontological life of the Aborigines and encompasses how they are linked to the contours of the landscape in which they live. Aboriginal actor Ernie Dingo tries to explain: ‘When you talk about it, you think about it in the back of your head — “Now hang on a sec, how did that story go?” — and that moment of thought would come like a dream. So it’s going back into the past through memory, rather than in the English sense, through the history books.’

The Dreaming is an extraordinarily complex body of stories that guide the Aborigines in their quest for water, hunting, fertility. Each of the Aboriginal tribes has its own stories, and these are sung in Songlines or Dreaming Tracks, the paths created by the ancestors during the Dreaming as they criss-crossed the country. This is one from the Grampian Mountains of Victoria.

The Gariwerd Creation Story

In the time before time began Bunjil, the Great Ancestor Spirit, began to create the world around us: rivers, mountains, forest, desert. He created the animals and plants. He appointed the Bram-bram-bult brothers, the sons of Druk the frog, to finish the task of naming the animals and making the languages and laws. At the end of his time on earth Bunjil rose into the sky and became a star, where he remains.

Читать дальше