William Goldman, double Oscar-winner and considered by many to be Hollywood’s pre-eminent screenwriter, should know a thing or two about the ingredients for a good story — or perhaps not, as his most famous quote is ‘Nobody knows anything.’ Goldman described in his memoir, Adventures in the Screen Trade , how one of the highest-grossing films of all time, Raiders of the Lost Ark , was turned down by every studio in Hollywood except Paramount. And Star Wars was passed over by Universal. ‘Nobody — not now, not ever — knows the least goddamn thing about what is or isn’t going to work at the box office.’

It’s hard to believe that, after more than fifty years in the story business, Goldman doesn’t have an inkling of what works and doesn’t work. After all, he’s the screenwriter of some of the most intelligent films of the 1970s and 80s — Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Marathon Man, All the President’s Men, The Stepford Wives, The Princess Bride …

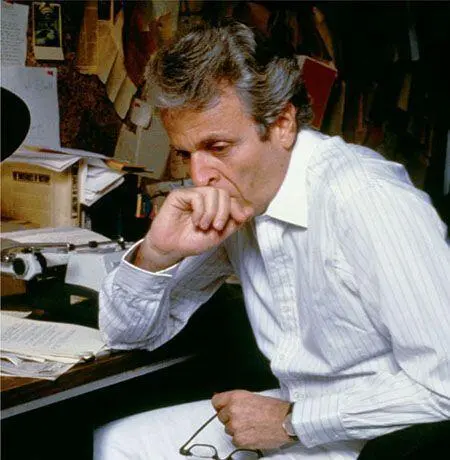

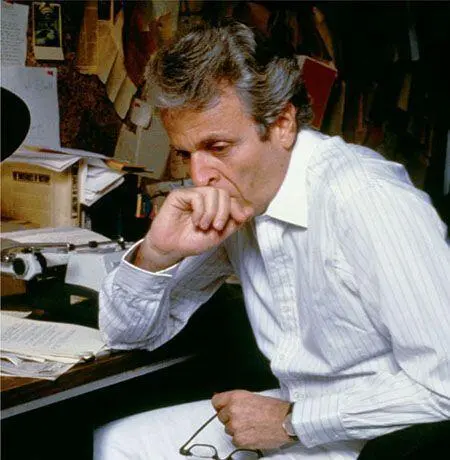

Goldman has described with real feeling the torment of writing.

‘Writing is finally about one thing: going into a room alone and doing it. Putting words on paper that have never been there in quite that way before.’ As he says, ‘The easiest thing to do on earth is not write.’ It’s reminiscent of Thomas Mann’s definition of a writer — a person for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.

So how does Goldman find inspiration for his stories? His screenplay for Marathon Man was adapted from his own novel and was made into an iconic thriller staring Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier in 1976. Goldman says it was based on two ideas. The first was what would happen if someone in your family wasn’t what you thought they were. (That’s the Dustin Hoffman character, who thinks his brother is an oil man and actually he’s a spy.) As for the second idea: ‘I was walking on 47th Street in New York — the diamond district — about forty years ago, and it was a hot day, and all the people that worked in the diamond district were wearing short-sleeve shirts, and you could see all the terrible marks from the concentration camps — because they were all Jewish and they all had their tattoos — and I got the notion: what if the world’s most wanted Nazi was walking along this street?’

William Goldman at his writing desk, 1987

From these two ideas emerged a compulsive story which climaxes in a torture scene which has put a generation of filmgoers off going to the dentist. The marathon-running student, Dustin Hoffman, has his teeth drilled without anaesthetic by Laurence Olivier, the former Nazis SS dentist at Auschwitz, who repeatedly asks the clueless Hoffman, ‘Is it safe?’

Goldman may insist that a walk along New York’s 47th Street gave him the germ of his story, but the point is any one of us could have been walking along that street and noticed the tattoos. Only a very few are able to carve a story out of the scene. It’s a bit like Michelangelo contemplating his block of marble — his genius is what he takes away, revealing the statue of David inside. Goldman has a mind that makes stories.

If you read through the movie trade magazines, there’ll always be a page somewhere advertising a piece of software or a seminar or a course that claims to teach you how to write. You can actually buy an application for your computer that supposedly allows you to build a story. It’s as if you can break down a story into a knowable, quantifiable entity that can be proscribed and created according to a formula. William Goldman reckons if it were possible to pre-programme a successful story, we’d all be doing it and making a fortune. Just look at the success of the film The King’s Speech .

‘There’s no logic to it. I mean, who in the name of God thinks there’s gonna be a successful worldwide movie that wins every honour about a king who has a stammer? It’s the worst idea I ever heard but, guess what, it was a fascinating story and it works.’

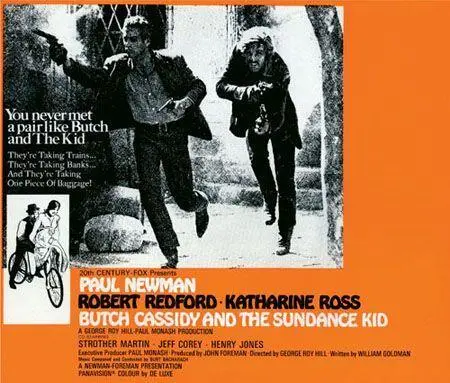

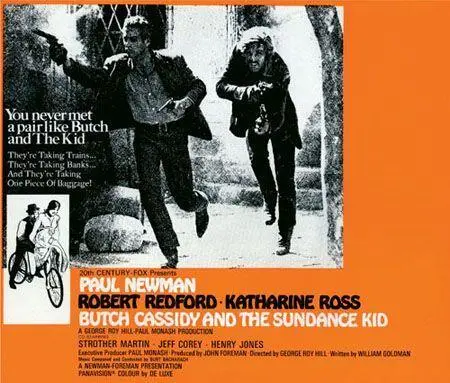

Casting is surely a vital element in the sense that it can completely alter the way you see the story. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is the most commercially successful of all the films Goldman has written screenplays for. It got him his first Oscar as well as establishing the buddy movie genre. The winning combination of actors Paul Newman and Robert Redford as the eponymous Wild West outlaws was obviously a factor, but Goldman insists that it was a piece of luck. The part of the Kid was supposed to have been played by Steve McQueen, who along with Newman was the biggest movie star in the world at the time. But they couldn’t agree on the billing — literally the size and positioning of their names — so McQueen pulled out. Jack Lemon was offered the part but declined because he didn’t like horses. Warren Beatty turned it down, as did Marlon Brando, who ‘disappeared off with the Indians’. So finally they got Robert Redford. ‘But who knows, if we’d had McQueen, if it would have been different. I don’t know, it might have been better, it might have been worse.’

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid won Goldman his first Oscar

Very little was known about the real-life characters Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Goldman spent years researching their lives before he wrote his screenplay, in which the two men run away to Bolivia.

‘When I tried to sell the movie, a guy in a major studio said he would buy it if they didn’t go to South America. And I said, “But they went to South America.” He said, “I don’t give a shit. All I know is that John Wayne don’t run away.” And I’ll never forget that sentence, “John Wayne don’t run away.” ’

Goldman’s experience suggests that, although the basic plotlines of stories are universal, our idea of the hero has changed. There was a time when heroes were heroes and, like John Wayne, they didn’t run away. What Goldman and his generation did in the late 1960s and early 1970s was to add a new twist — that you could have a hero who is self-deprecating and flawed and not made of granite.

Goldman remembers the thrill of discovering Homer as a child, immersing himself in the tales of the siege of Troy. And then reading Cervantes as a student and flinging his book across the room in a rage when Don Quixote dies. He’s almost apologetic in his admiration of these authors.

‘I’m gonna say something stupid … they were great at story. They really had fabulous stories to tell.’

Irishman James Joyce is acknowledged as one of the great and most original voices in world literature, but to many there’s an aura of impenetrability about his work that puts them off. Stephen Fry’s Desert Island book on Radio 4 was Joyce’s novel Ulysses and he urges anybody who’s never read it — or tried to and thought that it was too difficult — ‘just to let themselves go and swim into it, because, apart from anything else, there were never more beautiful sentences in any single book’.

Ulysses chronicles the journey of the middle-aged Jewish Dubliner Leopold Bloom through the streets of Dublin on an ordinary day, 16 June 1904. To a small but passionate group of devotees, an obsession with the book manifests itself in a rare literary curiosity: Bloomsday. Bloomsday is celebrated every year on 16 June, all over the world, often recreating events from the novel. In Dublin it’s frequently experienced as a lengthy pub crawl.

Читать дальше