Some people argue the culture we live in, with the competing attractions of television and books and computer games, makes Shakespeare too boring for an awful lot of people, simply not important. Is there any argument Simon can propose that would persuade someone to feel that Shakespeare is worth trying, that he’s not an unpleasant medicine that you have to take for the good of your soul?

Simon admits first off that Shakespeare does take work — there’s no way round it. He was lucky at school because he had teachers who managed to inspire him. He admits that there are boring bits in Shakespeare — bad bits occasionally — but it’s worth the effort:‘It really does yield extraordinary riches.’

The passion which Shakespeare inspires was evident when Simon was touring with Hamlet in Eastern Europe. One day he arrived in Belgrade, where the play’s poster with his face on it had been stuck up everywhere. He went into a shoe shop, and the woman serving shouted, ‘Hamlet! Hamlet!’ when she saw him and just kept saying, ‘To be or not to be,’ over and over again. The idea of that simple little phrase being repeated everywhere they went — even in China — is rather moving.

‘Utterly terrifying, poleaxing with fear because of all the baggage that it brings with you and because of the expectation that people have.’ That’s how David Tennant remembers feeling before his opening night as Hamlet at the National Theatre in 2008. He’d wanted the part since he was an eighteen-year-old drama student and he’d seen Mark Rylance play Hamlet when the RSC came to Glasgow.

‘I saw him at that very formative age and … it sort of sang. And you suddenly realize that these plays are deeper and wider and longer and better. Utterly contemporary, which is sort of a magic trick because it remains four hundred years old, and yet it seems to keep being reborn and rediscovered.’

Accepting the role of Hamlet — ‘like keeping goal for Scotland’ — was a brave thing to do. David was at the height of his TV career playing Dr Who and was put under intense media scrutiny in the run-up to opening night. David describes the newspaper articles with critics drawing up their top ten Hamlets of all time and wondering where David would fit in the list.

‘And you think, please Lord, let me just remember the lines. And then on the first night the News 24 truck draws up outside your dressing-room window, and you think, oh so now I’m going to fail on a global scale. Terrifying but also so thrilling to have those words at your command and to have that part in your palm for even a brief time. And you think, how do I begin? And of course you just begin by not worrying about it, which sounds terribly simple and isn’t, but there’s sort of no way round it other than just going, “Well, this character happens to say these lines here and they’re the first time they’ve ever been said.” ’

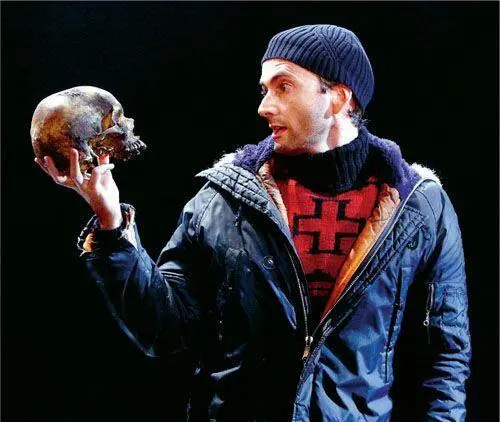

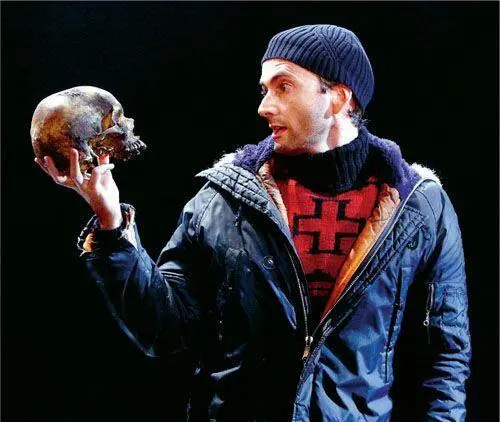

David Tennant holding Yorick’s skull, donated by André Tchaikovsky

Richard Burton said it helped him to remember that there’s always someone in the audience who will never have heard a single line of Hamlet before, so this is absolutely the first time for them. For other audience members, this is not the case. One night during a performance at the Old Vic Burton heard a dull rumble coming from the stalls; it was Winston Churchill sitting in the front row, reciting the words along with him.

Another of David’s favourite scenes is Act 2, Scene 2, when Hamlet says to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, ‘I can be bounded in a nutshell and count myself the king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams’.

‘You just get the sense that he hasn’t slept for days,’ says David. ‘He wants to sleep but can’t. And if you’ve ever had those long nights of the soul … it’s just that sense which is so vivid in that speech of “all I want to do is close my eyes but I can’t because it’s terrifying when I do, because my brain is so full of demons, and I hate myself so much”.’

Shakespeare talked a lot about sleep. He probably didn’t get enough of it or maybe he simply loved to sleep. The language he used — in Julius Caesar he calls it the ‘honey-heavy dew of slumber’; in Macbeth it’s ‘sore labour’s bath … balm of hurt minds’ — isn’t that fabulous?

The most identifiably visual moment of the play is the gravediggers’ scene, when Hamlet holds up the skull of the court jester and says, ‘Alas poor Yorick, I knew him’. It’s a memento of death, just like the ‘to be’ soliloquy. ‘I think the Yorick moment is much more specific,’ says David ‘because he’s looking at the material of a human being and he’s imagining that lips hung here and he’s trying to get his head round the actuality of death.’

The skull used in David’s performance was in fact a real one, donated by a concert pianist called André Tchaikovsky, who donated his head to the RSC in his will, to be used as a Yorick.

‘The first few performances holding a real human head was terribly potent because that is exactly what it’s about — we will become inanimate matter.’

As a young boy Mark Rylance spoke too fast to be understood by anyone. He had elocution lessons to slow him down, chanting tongue twisters and reciting poems and prose out loud. Mark found that learning bits of Shakespeare by heart and speaking the lines in front of people was the first time that he was able to express a whole range of emotions and ideas. He performed his first Hamlet as a sixteen-year-old school boy, then played him again aged twenty-eight and finally at forty. He reckons that’s about 400 performances in all.

When Mark was offered the part of Hamlet at the Royal Shakespeare Company it was a huge thing for him. He told the director, Peter Gill, that he planned to go up to Stratford immediately and read the old prompt scripts of all the luminaries who’d played the part, ‘like it was some big oak tree and I hoped I might add a little twig to the tree by being aware of all the choices they’d made’. Peter Gill told him not to be a fool — they’re all dead and gone or at least not playing the part any more. ‘ “It’s you who are alive now. Make sure it’s not set in outer space, but apart from that it’s you.” I said, “Yeah, but David Warner, he has such a …” “He was only wonderful because he was of his time,” said Gill, “and you’re of our time.” And that comment comes right down to the last ten seconds before you’re about to enter to say “To be, or not to be”.’

Just like Richard Burton, Mark had encounters with members of the audience who knew the play a bit too well. He had to be careful not to make his dramatic pauses too long. ‘In Pittsburgh there was a little old lady sitting next to her husband, and I came out right next to her in my pyjamas, all tearful and crying, and I said, “To be, or not to be”. And then I thought for a moment. And she turns to her husband and says, “That is the question”. And everybody heard it and laughed a bit. But I was able to say, “That is the question!” ’

Those sort of close-hand experiences with the audience stood Mark in good stead when he was appointed the first artistic director of the newly recreated Globe Theatre in 1995. He developed strong ideas about the relationship between actors and the audience, so that by the end of his ten years there he says he thought of the audience as more like fellow players. They were bringing the most important energy of the whole evening, a desire to hear a play. Mark likens it to a moment when he was playing Hamlet and delivering the line ‘Sit still, my soul: foul deeds will rise, though all the earth o’erwhelm them, to men’s eyes’.

Читать дальше