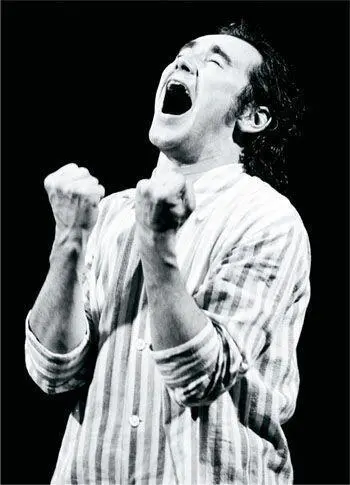

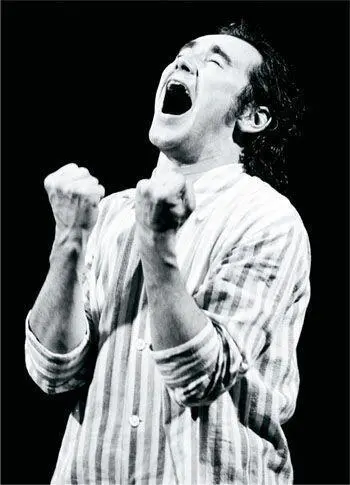

Mark Rylance as Hamlet

‘I remember performing the play out at Broadmoor special hospital and turning to a man and I wasn’t aware whether he was a nurse or a patient but I could see his imagination was completely with me. And in that moment between us I felt: who’s to say you’re the audience and I’m the actor? We’re in this together.’

Hamlet’s soliloquy

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die, to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream — ay, there’s the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause — there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment,

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

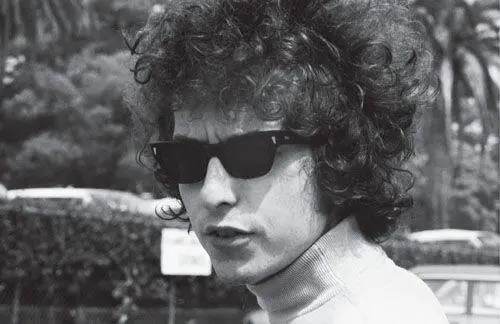

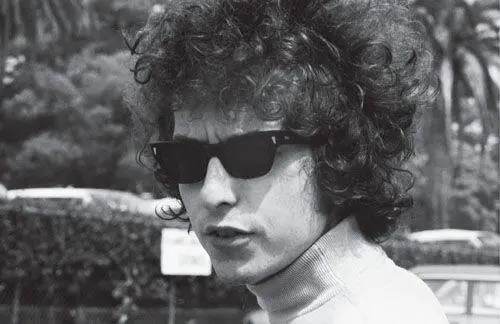

The Professor and Bob Dylan

Sir Christopher Ricks is one of the greatest literary critics of our day. He’s written seminal works on Milton, Keats, Tennyson, Beckett, T. S. Eliot, edited the Oxford Book of Verse , has been Warren Professor at Boston University since 1986 and until 2009 was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. He’s been described as holding all of English poetry in his head. He was also my very exacting professor at Bristol in the 1970s.

Photos of Ricks’ academic subjects adorn the walls of his elegantly spacious office at Boston’s Editorial Institute, which he now runs — the haggard, intense face of Samuel Beckett, T. S. Eliot besuited and respectable, and Bob Dylan, whom he has favoured with a compelling 500-page critical work entitled Dylan’s Visions of Sin . Sir Christopher is the critics’ critic. Scholarly, yes, with an extraordinary forensic ability for close textual analysis down to the use of the comma or apostrophe, but also very funny and in his seventy-seventh year as bright and acute as ever in not letting any lazy thinking get in the way of good criticism.

Stephen Fry almost had Ricks as his supervisor when they were both at Cambridge University in the 1980s. Now, thirty years later, he finally gets the chance of a one-to-one tutorial with the Professor. The ostensible subject is Beckett and Dylan and why poetry matters, but in typical Ricksian fashion they end up dancing all over the place. Here’s a flavour of the Ricks Masterclass, kicking off with the difference between poetry and prose.

Bob Dylan, a poet songwriter

CR : I think poetry is to be distinguished always from prose. They have different systems of punctuation.

SF : That’s a really good point because it’s a game people play to try and devise the best, most compact, most necessary and sufficient definition of poetry as opposed to prose. And you said different punctuation which sounds trivial but it strikes at the heart of it in a way, doesn’t it?

CR : Well, I think that it does. The line endings are significant in poetry or verse. They carry significance.

SF : So it’s the shape on the page. T.S. Eliot said that poetry is not about expressing emotion or personality, it’s almost the opposite. And people might say, but surely poetry is the excess, the demonstration of personality and emotion?

CR : You’re right, especially in a world in which too much is being made of the idea that poetry is self-expression. Though Eliot is always resourceful enough to know that you need a multiplicity of ways of talking about things. That is, a poem is in some ways like a person. In another way it’s like a plant. In another way it’s like a beautiful building. We need all these figures of speech. The key term from him, I think, is when talking about intelligence either in criticism or in poetry — he thinks of it as judging. It’s the discernment of exactly what and how much you feel in any given situation. So it doesn’t make poetry or literature the realm of feeling as against prose as the realm of fact or proof or argumentation. I think it’s a very, very beautiful formula in what it does with both thinking and feeling.

SF : And it requires a huge amount of honesty. Direct confrontation.

CR : Great honesty, including doubts about the rhetoric of honesty. So as one says, ‘I’ll be completely honest with you,’ as though in the ordinary way I was doing no such thing.

SF : Yes quite. We’ve started with Eliot, which is for some people the start of modernism and the time when a lot of the public turned off poetry. But while we’re on the subject of him there’s a precision, an almost miraculous ability to create lines which stick in the head like music. Anybody who’s read Eliot will probably say he’s one of the easiest poets to memorize a phrase from. And I wonder where that comes from. Why, for example, ‘the young man carbuncular’ and not ‘the carbuncular young man’ in a modern poem?

CR : Well it would partly be that — the striking turn of phrase, and that is indeed a turn, isn’t it? What it’s doing is imitating languages, ancient or modern, in which an adjective comes after a noun. The human form divine becomes the young man carbuncular and so on. So there’s something about moving. You’ve got to allow a shape to it. So I think he’s always interested in resisting either the tyranny of the eye or the tyranny of the ear. Each is inclined to take over. The eye will say every time you use the word ‘image’ it’s clear that imagination is seeing things. But every time you turn to a figure of speech that comes from hearing, you seem to be deaf to this.

SF : That’s a very good example of the close attention to language that people might find astonishing in your work. You go almost to the molecular and atomic level of a sentence and into the syllables and the actual structure of words and you find in them an energy and they are often the thing that causes the whole work to show itself.

And I suppose as much as anything, the problem that poets have to confront is that they’re making their art out of something that is common to all humanity. Unlike a painter who can go to a shop and get turpentine and acrylics and canvas and brushes or a musician who has a special language of augmented sevenths and special machines made of brass and wood. There’s another Eliot phrase — ‘to purify the dialect of the tribe’. So a poet has to take the same thing I use when I order a pizza over the phone and turn that into art. And does that mean poetry has two choices? One is to embrace the everyday and the other to try and get rid of it and to find a noble and elevated language.

Читать дальше