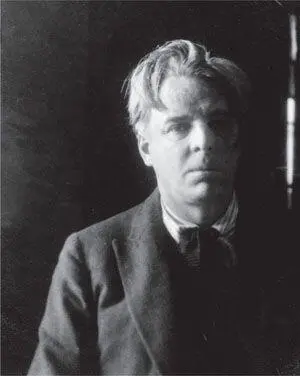

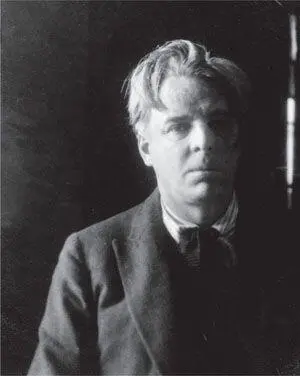

‘And for me that’s the magnificence of Yeats, that he was both a tremendous Irish patriot and an absolute auto-critic.’

He believes that Ireland has represented itself through its writers. He tells the story of Oliver Gogarty, a member of the early Irish Senate, who stood up one day and said to the other Senators, ‘We wouldn’t be here today in a Senate of an independent Ireland, were it not for the poems of someone like W. B. Yeats.’ He was affirming that the word can become incarnate, can become an action.

W. B. Yeats captured the essence of Irishness

Easter 1916

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born …

I write it out in a verse —

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

It becomes becomes clear in this Dublin pub that an unselfconscious delight in ideas and language are at the heart of good storytelling. There’s a great story Yeats picked up in Sligo about a man who went to a cottage and asked for a bed and breakfast, and they said, ‘Sure, but you have to tell us a story in return.’ And he had no story, so they kicked him out. He went to the next cottage, and they said, ‘Yes, you’re welcome, but tell us a story.’ No story, so he was booted out the door. So he went to a third house and he complained bitterly and described in detail his treatment in the other two houses. So the description of how he was treated for not having a story became the story itself, and he was taken in.

While it’s a particularly Irish story, it’s also a universal that any culture can understand and appreciate.

‘You make your destitution sumptuous, and that’s what Samuel Beckett did and why in some ways he is perhaps the central voice of this culture,’ Kiberd concludes.

‘In the last ditch,’ he concludes, quoting Becket, ‘all we can do is sing.’

In many ways it was a serendipitous time to be an Irish writer in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — comparable, perhaps, to being an English writer in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Just as Ireland created linguistic gold out of the cataclysmic changes after the Hunger, there’s something about the language in Elizabethan England that was growing and developing as the country found itself: the King James Bible, the outpouring of plays, the new words that were emerging and a new confidence and boldness in using them. And then, of course, there was Shakespeare.

Shakespeare and the Three Thespians

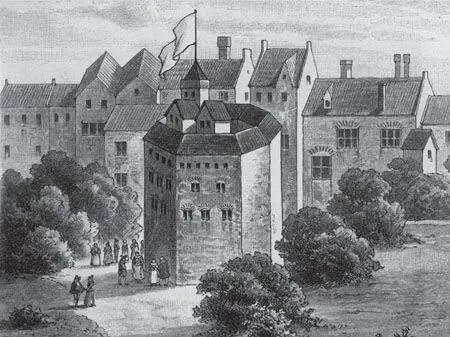

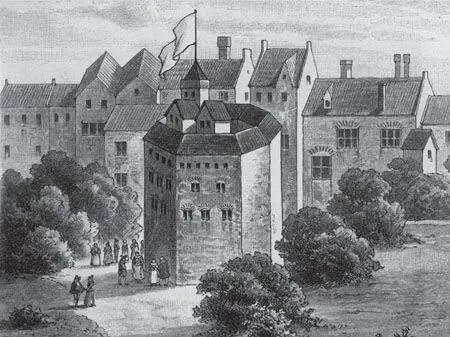

Imagine you could go back 400 years or so to wander the streets of Elizabethan London. You might pop into a tavern, hoping to bump into Shakespeare or Marlowe or Jonson or Webster, and watch as they drank and talked and scribbled, or go to the newly built Globe Theatre in Southwark on the south bank of the Thames and pay your penny to stand with the other ‘groundlings’ in the pit in front of the stage and experience for a few hours that extraordinary flowering of language and theatre that the world has never seen since. Shakespeare might be there acting in one of his own plays; and — it being 1600 — the performance on stage that night might well be his latest work, Hamlet .

There was a sort of explosion of words taking place in early modern English in the sixteenth century. What Shakespeare did was to give style and structure to the language, to mine its rich seam and to add to its vocabulary. He invented, or was the first to put in print, around 3,000 new words. You may think you don’t know any Shakespeare but of course you do. Expressions like in one fell swoop and it’s not the be all and end all ; or make your hairs stand on end, cruel to be kind, method in his madness, too much of a good thing, in my heart of hearts and the long and short of it. Eaten out of house and home, love is blind, foregone conclusion — the list goes on and on, and they’re all creations of Shakespeare. Clichés today, perhaps, but genius.

Someone (Stephen Fry, as it happens) once wrote that as theatre is a rhetorical medium and film is an action medium, so the perfect film hero is Lassie. The hero doesn’t need to speak. The boy’s on the cliff edge, Lassie looks, Lassie grabs the trouser leg, pulls the boy back … you just watch the action unfold. And the perfect theatrical hero is Hamlet, because everything is expressed in language, absolutely everything. It’s rhetoric, and he does it like no one else on earth. Hamlet explores sex, life and death, hope, revenge and despair. He’s utterly contemporary.

The Globe Theatre, c .1600

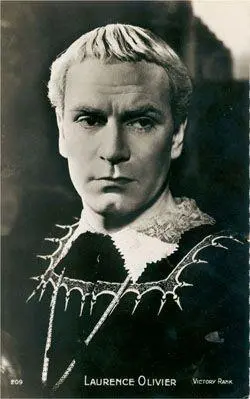

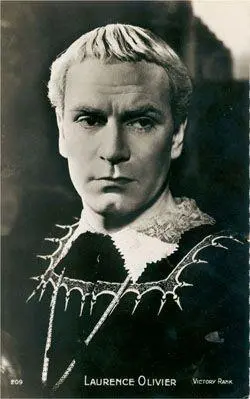

For this reason, the role of Hamlet is seen as the ultimate test for an actor, a theatrical Everest. The character is so full of complexities and the play itself is so well known that sleepless nights are spent worrying about how to bring something new to some of the most quoted lines in literature. A roll call of theatre greats have played Hamlet — John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, Derek Jacobi, Ian McKellan. Three actors who’ve all taken the part of the Prince in the last decade talk about the role: Simon Russell Beale played the student prince at the National Theatre in 2000 to rave reviews; David Tennant, best known as BBC TV’s Dr Who, was Hamlet in a Royal Shakespeare production in 2008; and Mark Rylance has played Hamlet three times — first as a teenager, then with the RSC in 1989 and again at the Globe Theatre in 2000.

Laurence Olivier as Hamlet, 1948

‘Absolutely terrifying’ is how Simon describes performing the ‘To be, or not to be’ soliloquy for the first time on stage. ‘Apart from it being so famous, it was scary because it’s such a simple question.’ He says it took him until well through the run before he got to grips with the power of the soliloquy — its calmness and self-control.

‘I get the sense that it was a radical exploration of a single human soul in a way that hadn’t been done before.’

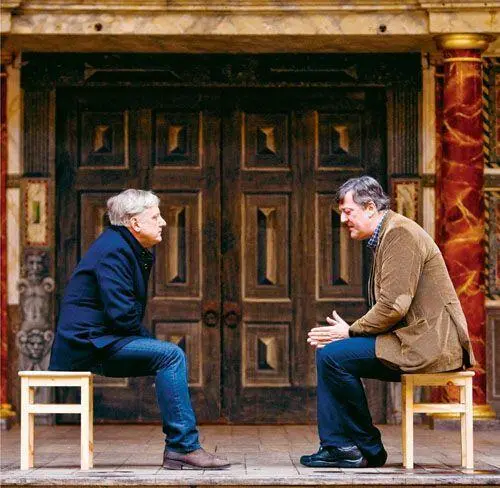

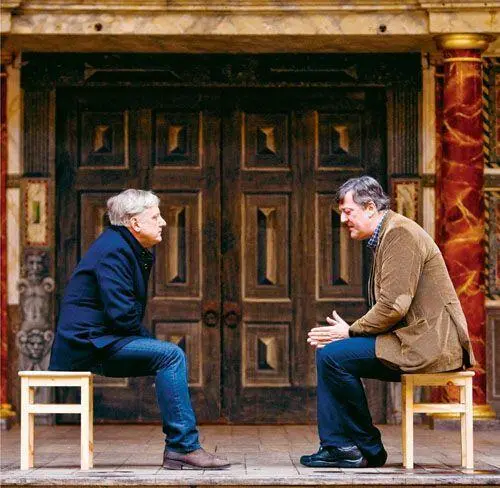

Stephen Fry and Simon Russell Beale in the Globe Theatre

For the Elizabethan audience, Hamlet must have seemed incredibly modern and cutting-edge. Macbeth , for instance, was set 400 years before, but Hamlet is completely different; he has a whole different set of morals and a whole new outlook on the world. The controversial American scholar Harold Bloom wrote a book called Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human in which he claimed that before Shakespeare there were no real, rounded, ambiguous, complex characters.

Читать дальше