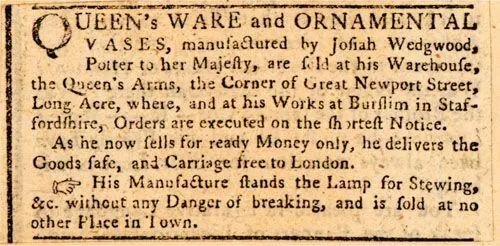

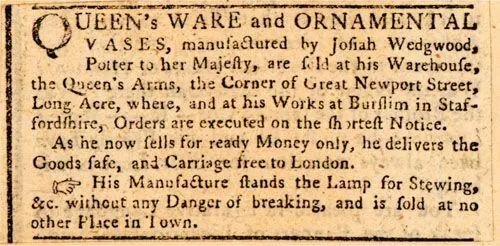

An early example of a Wedgwood ad in a newspaper, c. 1769

The Industrial Revolution and the greater availability of factory-produced consumer goods brought a growing awareness amongst manufacturers that they could create a need for a product amongst the middle and lower classes able to afford luxury items. Our friend Dr Samuel Johnson wrote one of the first articles on advertising in a 1759 edition of his magazine The Idler : ‘Promise, large Promise, is the soul of an Advertisement … The trade of advertising is now so near to perfection, that it is not easy to propose any improvement.’ He wasn’t very prescient, for at that very moment one Joshua Wedgwood was founding his pottery workshop and he had very big ambitions about improving advertising technique. Wedgwood was one of the first industrialists to recognize the importance of creating a market through advertising and used newspapers ads, posters, publicity stunts, give-away promotions and money-back guarantees to persuade people of the need for a must-have Wedgwood vase or a twenty-piece dinner service.

Increased competition amongst manufacturers and a growing public sophistication opened the way for agencies in the late nineteenth century who promised to create and run advertising campaigns for the client. Advertising had become a profession. The advent of radio and television extended the mass reach of advertising, revolutionizing its persuasive potential. This is the world of advertising we’re all familiar with — the TV commercials and product placements in films and internet pop-ups.

On the reception desk of the west London ad agency Leo Burnett is a large bowl of green apples, a reminder of the humble beginnings of the founder, Mr Burnett, who established his agency in Chicago in 1935 with just one account, a staff of eight and a bowl of apples on the front desk. Legend goes that, when word got around Depression-hit Chicago that Leo Burnett was giving apples to visitors, a newspaper columnist wrote, ‘It won’t be long till Leo Burnett is selling apples on the street corner instead of giving them away.’ Leo was a wizard with visual imagery and created the iconic brands for the Jolly Green Giant canned peas and corn, Kellogg’s Tony the Tiger — ‘They’re GR-R-R-E-A-T’ — and most famously the Marlboro Man for Philip Morris, who were persuaded to repackage their woman’s cigarette as a rugged man’s smoke. Today, Leo Burnett is one of the world’s leading advertising organizations.

Don Bowen is a creative director at the agency’s London office and currently in charge of the Kellogg’s and Daz accounts. He began in the business thirty years ago as a copywriter and manages to turn on its head the adage of a picture being worth a thousand words.

‘Words are tremendously important in advertising because there have been hardly any ads where there have been only images that can make a lot of sense. The Economist has done this, once or twice, but most of the time most ads have words in them, and very often the words can be worth a thousand pictures.’

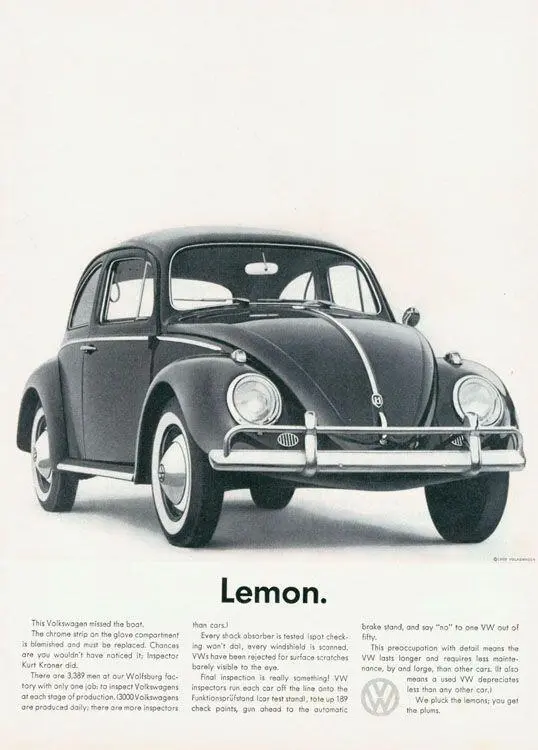

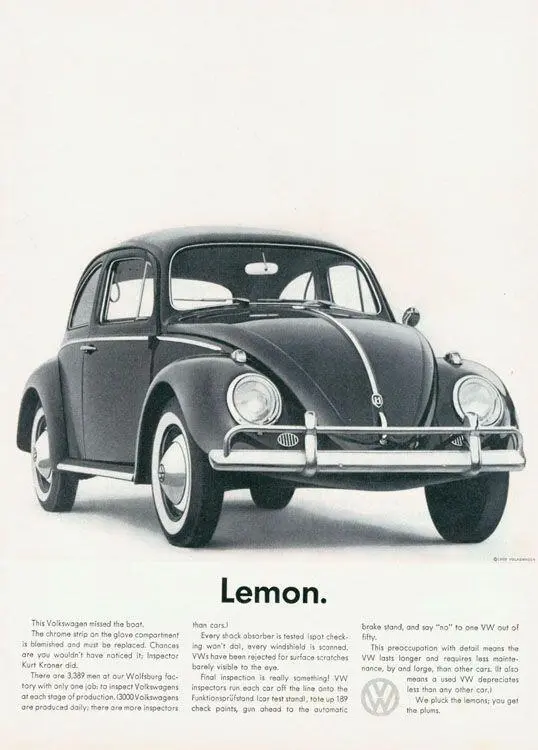

Don gives the example of the Volkswagen advertising campaign in the 1960s. The American ad agency DDB faced an apparently impossible task — selling Hitler’s favourite car to the Americans, a decade or so after the Second World War. What they came up with is known simply as ‘The Lemon’ — a black-and-white picture of a Beetle car with the one word, ‘Lemon’, underneath. The story below explained that this car had been rejected by the quality-control inspectors because of a blemish on the glove box. ‘We pluck the lemon; you get the plums,’ ran the end tag. It intrigued readers that a company should be critical of one of its own cars. Then it hooked them with its assurances of rigorous inspection. It was an approach to advertising that the Lemon’s creator, William Bernbach, saw as part of a creative revolution, rethinking how advertising works. (For the car rental company Avis, his agency made an apparent failure a virtue: ‘We’re only Number 2. We try harder.’)

The 1960s Volkswagon campaign was part of a creative revolution in advertising

‘Lemon’ is an example of what copywriters call the endline, like ‘Probably the best lager in the world,’ or ‘Refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach,’ or ‘Don’t just book it, Thomas Cook it.’ Huge amounts of time are spent getting them right, distilling a number of ideas into one three-, four- or five-word end line. ‘English is a particularly good language for being able to play gags, to word play, to sum up an idea pithily,’ says Bowen, ‘like “You’ll never put a better bit of butter on your knife.” ’

TV commercials in the UK particularly like to use endlines and some of the best slogans (and quirky storylines) have become as much a part of our culture as classic TV shows. Many of us can recite advert slogans from our childhood as easily as we can chant a nursery rhyme. ‘Don’t forget the Fruit Gums, Mum,’ Beanz Means Heinz, ‘All because the lady loves Milk Tray.’ ‘Opal Fruits! Made to make your mouth water’, ‘For Mash get Smash!’, ‘Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet’

‘The end line has got to resonate with people,’ says Bowen. ‘There are thousands of end lines out there, most of which we don’t care about. But when you get it right and there’s some emotional connection with the end line, then I think you can tell the story which leads up to it again and again, which is what makes the words so powerful.’

Today the notion of advertising as an art of persuasion is seen as rather an old model. The days of the unique selling propositions — USPs — have gone. One detergent really isn’t that different from another. So you have to attract people to your brand rather than persuade them that it’s the right product. Advertising has become much more about engaging people emotionally, and the most successful way of doing this is by creating a story about the brand.

Don’s favourite ad from his own agency in recent years is the McDonald’s poems.

Now the laborers and cablers and council-motion tablers were just passing by …

and the first-in types and lurking types and like-to lose their-gherkin types and suddenly-just-burst-in types were just passing by.

He likes the attention to detail of the words, the internal rhymes, the little word jokes. The most interesting thing of all was — ‘it was so human’.

Does Bowen worry that this storytelling in advertising, the communal appeal of the sales pitch, will be lost as the consumer is targeted with individual messages and offers via the internet?

‘I think there will always be good stories to tell. Whenever it’s difficult in advertising, I always say to myself, this brand, with any luck, is going to be around in fifty years, and somebody is going to need to advertise it. So there will be a story to tell. The question is just finding it.’

The Most Famous Ad Man in the World

He has the looks, the pipe and the suit of one of the original Mad Men in the American TV drama set in the advertising world of the 1950s and 60s. Dubbed the ‘King of Madison Avenue’ and the ‘Pope of Modern Advertising’, David Ogilvy rewrote the rules of advertising with his emphasis on brand image, consumer research and the Big Idea. ‘Unless your advertising contains a big idea,’ he insisted, ‘it will pass like a ship in the night.’

Читать дальше