Propaganda, said the English academic Francis Cornford, is ‘that branch of the art of lying which consists in very nearly deceiving your friends without quite deceiving your enemies’.

Advertising may have moved on since the Golden Days of Madison Avenue, but propaganda has never shied away from its primary role of explicit persuasion. In its most basic form, it’s about disseminating information for any given cause, and it’s been around for as long as we’ve had organized societies with messages to promote.

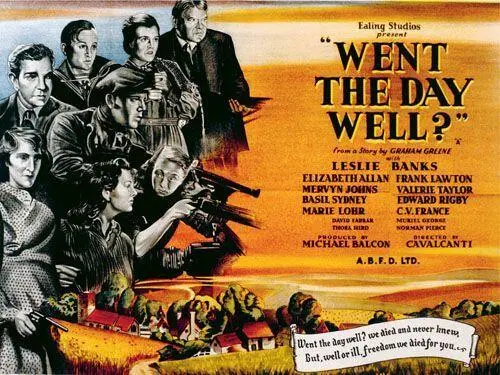

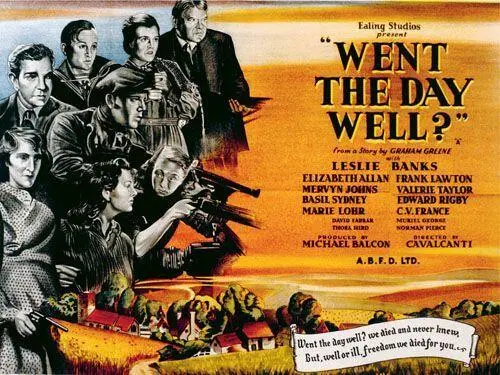

It doesn’t mean it can’t be entertaining or subtle. Some of the best British propaganda was produced in the dozens of films made during the Second World War. Of course, some of them are truly awful, cringe-making examples of pragmatic jingoism, but others have become classics, like the 1942 Went the Day Well? (based on a Graham Greene short story), which tells how a vanguard of Germans, disguised as British soldiers, infiltrates a sleepy, idyllic English village to prepare the way for invasion. The villagers eventually manage to fight back, with a combination of British pluck, ingenuity and surprising ruthlessness (in one scene the local postmistress kills a German with an axe), and Britain is saved. The purpose, of course, was to warn against the danger of invasion (which, in fact, by 1942 was not so real) and ram home the need for constant vigilance; to portray German brutality and evil and, above all, to extol British patriotism, sacrifice and bravery — all standard war propaganda.

But it’s war propaganda done with some style and artistry, with touches of pathos, and the occasional satirical side-swipe at other enemies — like the great line, completely un-pc nowadays, of course, when a young village lad is being urged to do his part in defending the British Isles. ‘You know what “morale” is, don’t you?’ someone asks him. ‘Yes,’ he declares, ‘it’s what the wops ain’t got!’ There’s black humour, rousing British cheeriness and flashes of shocking realism which knock against the rural idyll cliché, all of which make it a more powerful piece of cinema, and therefore a more powerful piece of propaganda.

Propaganda can be blunt or subtle, blindingly obvious or relentlessly and cleverly suggestive, but its aim has always been to persuade and get everyone on message, whatever the method. It’s been used by regimes to lie, dissemble, exhort, convert and cover up. Totalitarian regimes have created huge ministries of propaganda, while democracies have given birth to their bastard offspring — the PR companies and spin doctors.

Propaganda films were hugely popular during the Second World War

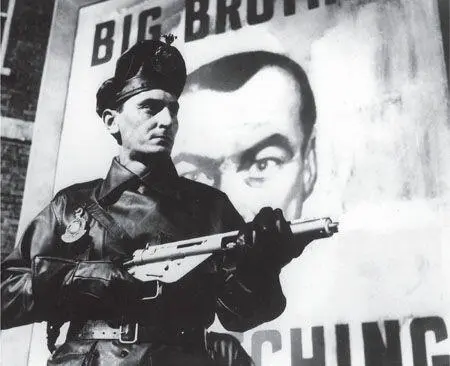

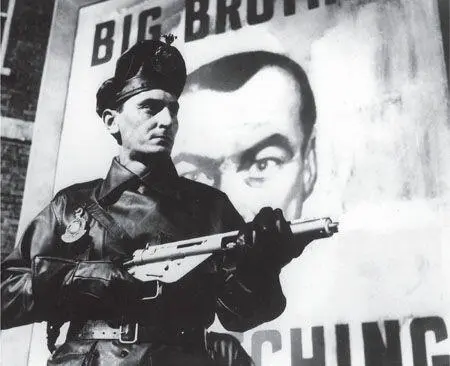

It’s been wildly successful, but thankfully we usually end up seeing through it. In works of fiction like George Orwell’s 1984, the propaganda ministry realizes that to really change people’s minds it needs to change the language itself. If you can’t say it, you won’t think or feel it. So the Newspeak dictionary gets slimmer and slimmer as more and more words are ‘disappeared’. Newspeak, where only prescribed words can be used, is the propagandists’ dream.

‘It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words’

(1984)

Newspeak (pronounced New-speak) is the fictional language created by George Orwell in his novel 1984 . It’s closely based on English but with a vastly reduced and simplified vocabulary and grammar. The aim of the totalitarian government of Oceania is to make language so basic, so sterile that any alternative way of thinking to that prescribed by the regime (thoughtcrime) is impossible. In a nightmarish twist on Sapir — Whorfism, how can you have ideas of freedom or rebellion if there are no words for them?

‘In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible,’ explains the character Syme, a Newspeak specialist, ‘because there will be no words in which to express it … [We’re] cutting the language down to the bone … Newspeak is the only language in the world whose vocabulary gets smaller every year.’

Richness of language is anathema to the Party. Words must be stripped of superlatives or negatives and reduced to the absolute minimum. ‘Uncold’ for warm; ‘unlight’ for dark. Good and evil and all nuances in between are distilled into six words: good, plus good, doubleplusgood, ungood, plusungood and doubleplusungood.

Many of Orwell’s Newspeak words appear to be modelled on Esperanto. For instance, in Esperanto the opposite of good, bona , is malbona , and its extreme is malbonega — literally ‘very ungood’. When he travelled to Paris in 1928 for his ‘down and out’ period, Orwell is thought to have stayed with his aunt Nellie and her partner, Eugène Lanti, a leading Esperantist. According to his biographer Bernard Crick, Orwell told a friend that he had gone to Paris ‘partly to improve his French’, but had to leave his first lodgings because the landlord and his wife only spoke Esperanto — ‘and it was an ideology, not just a language’. So, whether out of antipathy to Esperanto or a fascination with a language constructed for political aims, Orwell was clearly inspired.

‘Thoughtcrime’ would be impossible and everyone would speak ‘Newspeak’ in Orwell’s 1984

In 1984 , Newspeak was still being introduced as an official language, but the expectation was that Oldspeak, the Newspeak term for English, would have disappeared by 2050; all literature from the past — apart from technical manuals — would be unintelligible and untranslatable. The ‘all men are equal’ passage from the Declaration of Independence would be reduced to a single word: crimethink.

Orwell’s 1984 introduced an astonishing number of words and concepts denoting totalitarian authority into the English language — Big Brother, the Thought Police, Room 101, doublethink, unperson, thoughtcrime. Chilling slogans resonating as clearly today as they did over sixty years ago — ‘Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’

It’s an idea far more powerful and frightening than the most destructive of weapons: loss of language leads to loss of our history and, ultimately, loss of our selves.

In the Western liberal tradition we’re pretty sniffy about overt propaganda — for us, it’s a negative, dishonest tool — but other systems and ideologies see it as a positive means of motivating the population and keeping it under control.

One of the first modern propagandists was Josef Goebbels, who became Hitler’s Reich Minister for Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Public Enlightenment and Propaganda). It’s chillingly ironic that he should use the inference of the Enlightenment in his title when he was the master of the dark arts, but then ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ (‘Work Makes You Free’), the slogan that adorned the entrance to the extermination camps, was hardly a promise they kept.

As editor of Der Angriff ( The Attack ) Goebbels masterminded Hitler’s attacks on his opponents, which were particularly effective in the election of 1932, when Hitler become Chancellor. He used radio, cinema and spectacular demonstrations, which culminated in the famous Nuremberg rally. His showmanship helped to get the Nazi message across and then keep the German people firmly corralled within the Nazi ideology, but his techniques were just as often crude. He was interested in effectiveness, not art. ‘Good propaganda is successful,’ he declared. ‘Bad fails to achieve its desired result.’

Читать дальше