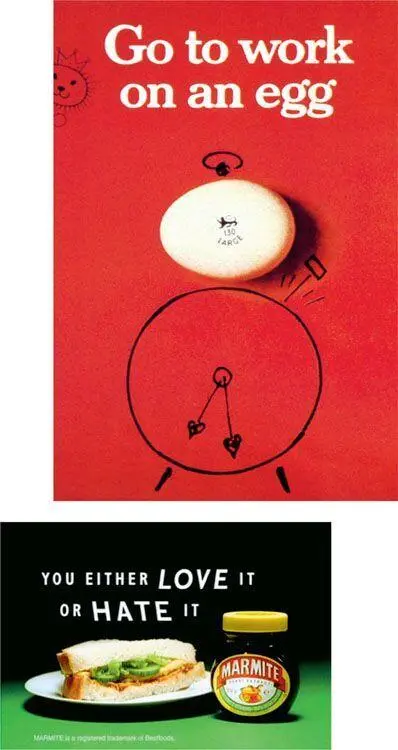

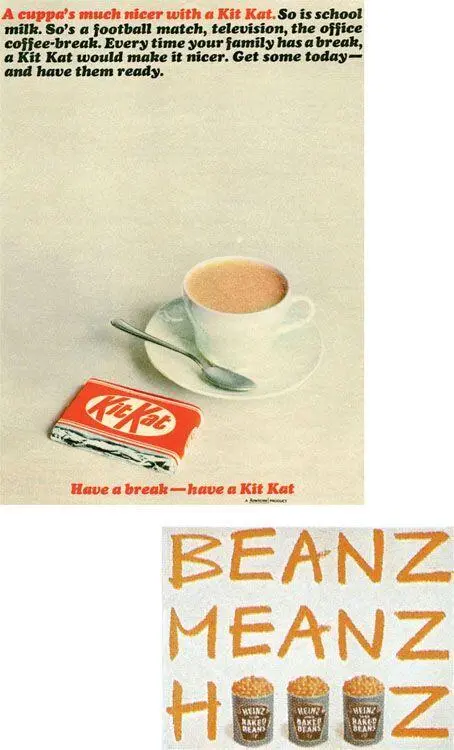

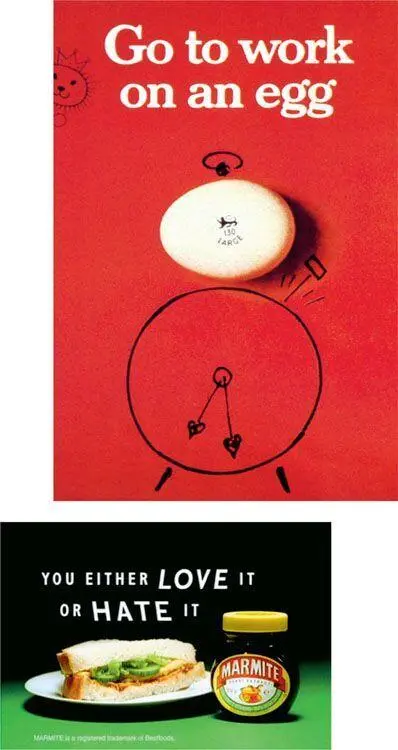

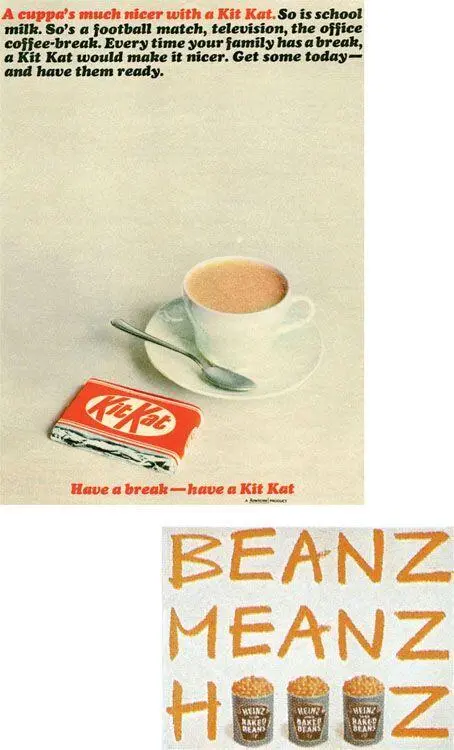

Iconic adverts demonstrate the power of the word

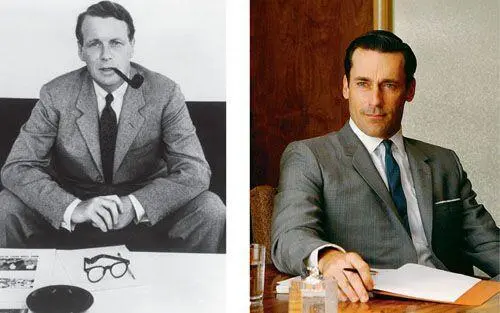

Born in Surrey in 1911, this eccentric Anglo-Scot started his working life as a sous-chef in Paris after being sent down from Oxford University. A job selling Agas, the most expensive cookers on the market, door to door in Scotland during the Depression gave him the experience of direct selling (albeit to stately homes and convents) which influenced his later career. He wrote the company’s sales manual, The Theory and Practice of Selling the Aga Cooker , which began ‘In Great Britain, there are twelve million households. One million of these own motor cars. Only ten thousand own Aga Cookers. No household which can afford a motor car can afford to be without an Aga.’ The twenty-four-year-old Ogilvy offered a variety of personal tips including: ‘ The good salesman combines the tenacity of a bull dog with the manners of a spaniel. If you have any charm, ooze it.’

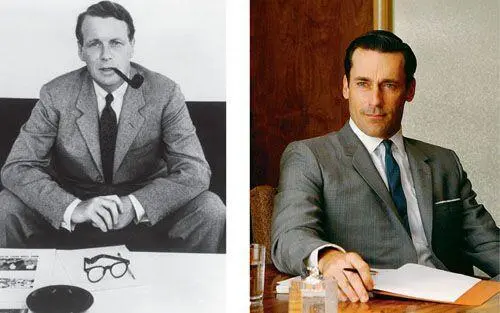

David Ogilvy and Mad Men ’s Don Draper

After some initial training in the ad agency Mather & Crowther, he left London at the end of the 1930s to seek his fortune in the United States. There he was hired by pollster George Gallup to work with him at his newly founded audience research institute; he and Ogilvy spent months travelling from New Jersey to Hollywood and back, quizzing the public about their movie star preferences and selling the research to studio heads and movie producers. After working for the British Secret Intelligence during the war and a brief period living with the Amish as a tobacco farmer, Ogilvy finally moved to New York in 1948. With virtually no experience in advertising and, as he recalled, ‘no credentials, no clients and only $6,000 in the bank’ $6,000 in the bank’, he opened up his own agency in a two-roomed office with a staff of two. Within a decade he’d built Ogilvy & Mather into an advertising powerhouse that attracted the biggest clients in America. He employed all the skills he’d learned in door-to-door selling and audience research along with a flair for language, a strong visual sense and a personal showmanship — he was known to dress in a full-length black cape with scarlet lining.

The bulk of Ogilvy’s notable advertising campaigns were produced in these early years. He called them his Big Ideas. He outlined how to recognize one by asking five questions. ‘Did it make me gasp when I first saw it? Do I wish I had thought of it myself? Is it unique? Does it fit the strategy to perfection? Could it be used for thirty years?’

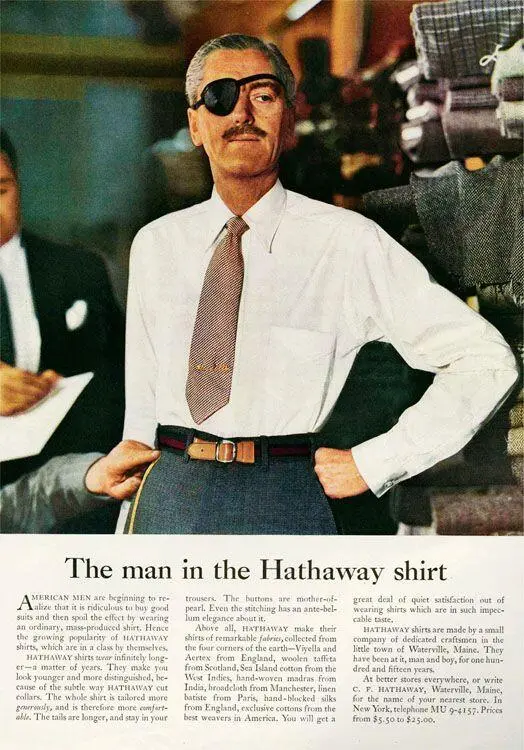

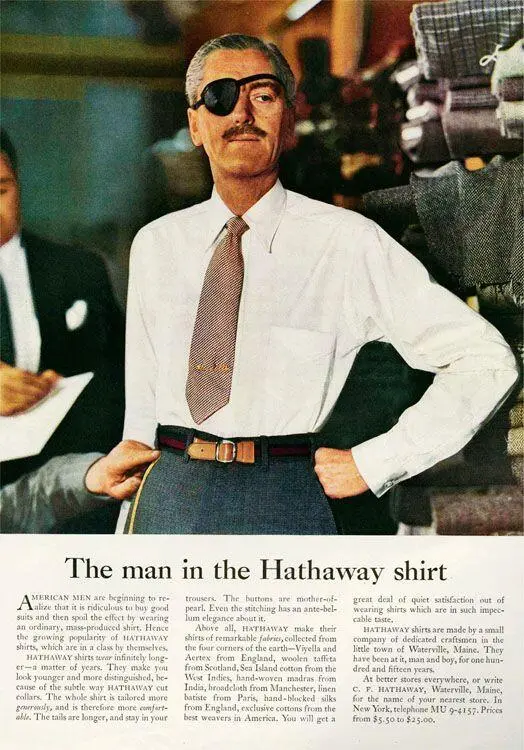

An early iconic campaign was for a small clothing company called Hathaway. On the way to the photo shoot, Ogilvy stopped to buy some eye patches. The photograph, ‘The Man in the Hathaway shirt’, caused a sensation. The clothing firm couldn’t keep up with demand. The eye patch had given the ad what Ogilvy called ‘Story Appeal’. The reader was intrigued by the model with one eye and wanted to find out more. Other campaign successes followed: ‘At sixty miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock,’ and ‘Only Dove is one-quarter cleansing cream’ (which helped make Dove America’s bestselling soap). When Ogilvy won the Shell account in 1960, other major American advertisers — General Foods, Campbell Soups, American Express — jumped on board.

Ogilvy was credited with introducing the novel idea (for the 1950s certainly) of the intelligent consumer. In his bestselling Confessions of an Advertising Man he included his most famous aphorism ‘The consumer is not a moron. She is your wife. Don’t insult her.’

Words were the backbone of Ogilvy’s campaigns. His biographer, Kenneth Roman, worked for him for twenty-six years and described the ad man at work.

The eye patch gave the ad ‘Story Appeal’ and caused a sensation

Being edited by Ogilvy was like being operated on by a great surgeon who could put his hand on the only tender organ in your body. You could feel him put his finger on the wrong word, the soft phrase, the incomplete thought. But there was no pride of authorship, and he could be quite self-critical. Someone found a personally notated copy of one of his books in which he had written cross comments about his own writing: ‘Rubbish,’ ‘Rot!’ ‘Nonsense.’ He would send his major documents around for comment, with a note: ‘Please improve.’

Ogilvy retreated to a chateau in France in the 1970s, unconvinced by the direction advertising was taking — less direct-sell, more art form.

I do not regard advertising as entertainment or art form, but as a medium of information. When I write an advertisement, I don’t want you to tell me that you find it ‘creative’. I want you to find it so interesting that you buy the product . When Aeschines spoke, they said, ‘How well he speaks.’ But when Demosthenes spoke, they said, ‘Let us march against Philip.’

When Ogilvy died in 1999, the Leo Burnet agency placed a full-page ad in the trade papers. It read: ‘David Ogilvy 1911 — Great brands live forever.’

Oratory is a powerful ally of the written word because a great public speech is a potent means of communication. It can persuade, move, convince, agitate, enlighten and — yes — manipulate, and history is littered with examples of oratorical tours de force, from Cicero’s attacks on Mark Antony to Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’.

The art of oratory goes back to ancient Greece, where public speaking was considered an essential part of education. Socrates, Aristotle and Plato discuss it at length, and it remained a central part of Western liberal humanistic education into the twentieth century. Lawyers, politicians and entertainers all need to be good orators, and it comes in handy if you’re asked to be a best man or after-dinner speaker. Wit, humour and the habit of reasoned arguments are all part of the armoury of the orator. It’s not essential but it helps if you believe in what you’re saying, as the best examples of oratory bear out.

The art of oratory is more than just the words and the arguments. The American writer Gore Vidal pointed out that in ancient Rome the senators were really drama critics, critiquing not only the contents of one another’s speeches, but the style of delivery. And former President Bill Clinton says: ‘A lot of communication has nothing to do with the words; a lot of it is just your body language, or your tone of voice, or the way you look in your eyes’.

Clinton is one of the best-placed (and highest-paid) contemporary orators to remind us of the challenge in delivering a truly great speech:

‘You measure the impact of your words,’ he says, ‘not on the beauty or the emotion of the moment but on whether you change not only the way people think, but the way they feel.’

There is fine oratory to be found in fiction too. Shakespeare is a great place to look, of course: Mark Antony’s funeral oration over the body of Julius Caesar in Act 3. The opening words — ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears!’ — along with ‘To be, or not to be’ and ‘Out, damn spot’ and a dozen others — must be among the most-often-quoted lines of Shakespeare, but the whole speech is a massive 137 lines of verse, in which Antony works the crowd and succeeds in changing the minds and hearts of the Roman mob. He uses every oratorical trick in the book, every tool of rhetoric to turn their hostility towards him and Caesar into grief for their murdered emperor and rage against Brutus. Gradually, he builds his argument by suggestion, ambiguity, calculated flashes of anger and grief, hypnotically repeated cadences — ‘Brutus is an honourable man’ — and by persuasion, artifice, sneaky cleverness and superb rhetoric, he brings the crowd over to his side. It’s a piece of theatre, performed by a duplicitous man who is a master of oratory.

Читать дальше