To this end Goebbels exploited racism, xenophobia and envy to the limit and sold the idea of the master race and the thousand-year Reich. His power and influence dwindled the more successful the Nazi Party was in extinguishing any opposition. There was simply less need for that sort of propaganda when no one dared complain or criticize, and by the beginning of the war his main task had been accomplished. What he did understand, however, was the need for the German people to have some light relief from the rigours of war and he became the David Selznick of the Nazi movie industry, producing an endless supply of frothy comedies and romances from the famous UFA studios on the outskirts of Berlin. It’s hard to imagine Nazi comedies now.

The propaganda — the control of what people were to believe, and the way they were to live — went far beyond overt messages and the production of films. Goebbels’ influence was pervasive. Holiday complexes and cruise ships were built for the Nazi worker. The KdF ( Kraft durch Freude — Strength through Joy) became the largest tourist operator in the world, and Goebbels’ ministry was even given the task of enticing foreign tourists to spend their holidays in Germany. By 1939 over 25 million people had been on KdF holidays — though, unsurprisingly, few came from overseas. KdF also built the first VW Beetle and marketed it as the workers’ car — a subtle blend of propaganda and advertising.

The thing about propaganda is, it doesn’t matter what the message and purpose is — it could be anything — the point is finding ways of promoting it and ensuring that people believe it. Take Stalin in the Soviet Union and Chairman Mao in China, masters of propaganda both — they could give Goebbels a run for his money. They used similar methods to the Nazis, but they were promising different results: a utopian socialist society, rather than the thousand-year Reich.

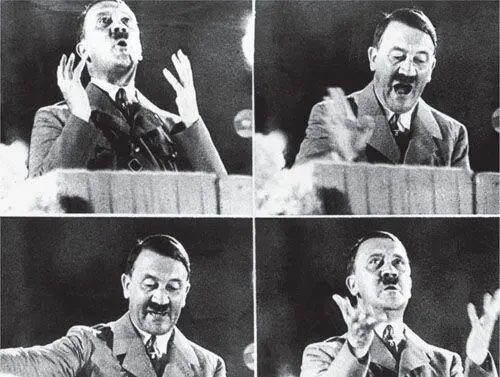

Adolf Hitler demonstrated impressive showmanship

All these dictatorships made extensive use of the printed word, speeches and, especially, posters. Stalin’s ambitious Five Year Plans, with their slogans exhorting workers to up their quotas and defeat the imperialists, were none too subtle, but the images of a smiling benevolent Uncle Joe did much to win the proletarian heart. In China, propaganda was taken to a new level with Mao’s continual revolutions within the revolution, each new wave designed to direct and control, under the guise of improving the nation and the lives of the people.

The Hundred Flowers Movement of 1957, for example, was a short-lived experiment in asking intellectuals to criticize the direction of the revolution. ‘Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting progress in the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land,’ was Mao’s initial premise. But when the criticisms became personal attacks on him he ruthlessly squashed it and effectively killed off any further intellectual debate.

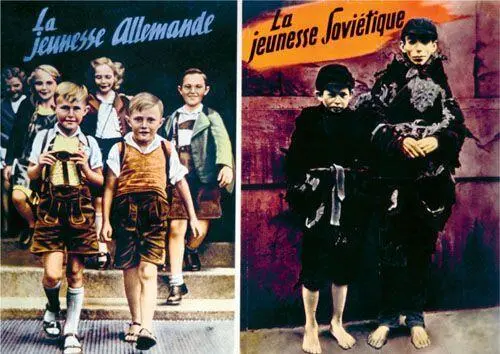

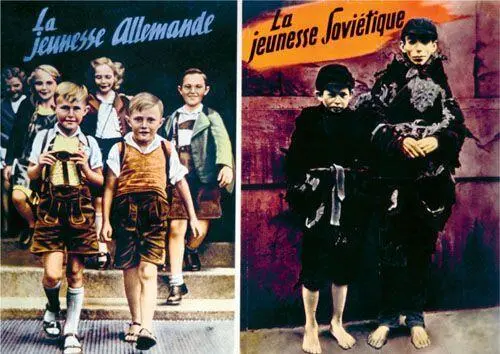

German propaganda was explicit and forceful. This example compares healthy German children with hungry, barefoot Russian children

Propaganda turns language upside down. It twists meaning and says the opposite of what it does. (It’s all in 1984 — have a look again. ‘War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.’) In his attempts to neutralize any further division within the party, Mao launched ‘The Great Leap Forward’ in 1958. Propaganda was used extensively to mobilize the masses and change the country from a predominantly agrarian economy to an industrial one. But there was no leap forward. The opposite happened, with catastrophic results. An estimated 20–40 million people died of starvation as the economy went into freefall.

And that’s where another side of propaganda kicks in. When the reality is not as the propaganda promises, just keep pumping out the message until people are swamped. Mao’s ‘Little Red Book’ was one of the tools of revolution which flooded the consciousness of millions of citizens with the wisdom and pithy sayings of the Chairman. It was impossible to escape the message. The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department printed a total of 1,005,549,800 copies of the book, in sixty-five languages. That’s over a billion ‘hits’ of propaganda in a pre-internet age.

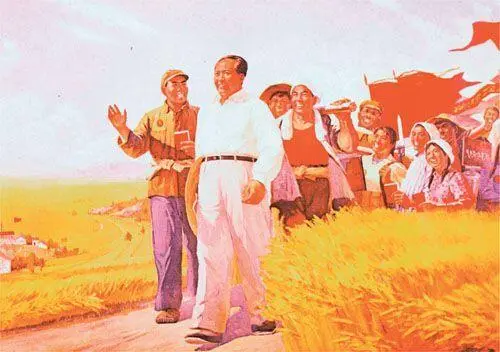

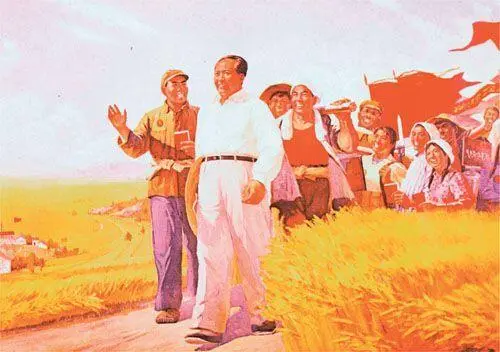

Chairman Mao with peasants during the Cultural Revolution of 1966

Of course, as well as making some fine war films, Western society has put out its fair share of outright wartime propaganda. Lord Kitchener’s recruitment campaign during the First World War was more direct than anything dreamed up by the communist propagandists, and Uncle Sam was no slouch either. Today’s messages, though, are couched in subtler and more entertaining ways. The US Defense Department, through the US Army’s Office of Economic and Manpower Analysis, has developed its own video game, ‘America’s Army’, to try to lure new recruits. Available as a free download, it’s been a huge success with over 8 million registrations.

Today’s politicians in general, though, have a much tougher job getting their message across in what the PR chaps would call ‘a crowded marketplace’. As ad man Don Bowen says, ‘Political slogans are still useful because they sum up the approach that the political party is moving in. The difficulty is there’s always somebody with an antithetical political statement that they’re trying to get over. So, unlike propaganda, when there’s only one story in town, which was true in Nazi Germany and in Mao’s China, here there are many stories. We have choices. There isn’t just one beer that says, “Probably the best lager in the world,” there’s another beer that says, “Refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach.” And there’s another beer that’s saying something else. So you never just get your own way.’

Well, that’s democracy for you. And in a democracy, people are free to pick and choose, and there are many, many different voices we can listen to, or ignore. And, generally, we prefer the simpler message. Don’t make it too complicated, or it’ll just get lost. Hitler knew that very well. ‘The most brilliant propagandist technique will yield no success unless one fundamental principle is borne in mind constantly,’ he said. ‘It must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over.’ Which is as true today as then. A slogan like Prime Minister David Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ struggles to be heard, so little wonder he has to repeat it every time he’s on the radio or TV.

Does ultimate resistance to the power of state propaganda depend on there being so many channels of communication, so many messages, that no one authority or idea can dominate? It’s true that even within totalitarian regimes the profusion of social network sites like Twitter and Facebook is chipping away at their hegemony. The events in the Middle East and the Maghreb in 2011 show just how difficult it is to contain information and channel people’s thoughts. When a young street seller in Tunisia sets himself alight because he can no longer fight the system which makes scraping a living almost impossible, and a very short time later his story is texted and tweeted and posted round the world — that’s when ideas can’t be corralled. When so-called ‘citizen journalists’ can upload pictures and videos of events to the internet in a matter of minutes, then the windows of communication are well and truly open.

Читать дальше