Nevertheless, there is a growing number of people for whom the book means very little. In fact, apart from in school, they may never read a book. It doesn’t mean they don’t read, simply that they never open a physical book. Electronic books have all sorts of advantages. In parts of the world where schools and libraries can’t afford books, accessing a database of information in cyberspace is a cheaper alternative. Archives can be accessed with the press of a button — with one touch you can be inspecting the writing on a Sumerian clay tablet; another touch and you’re gazing at a fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript. Unlike the printed book, e-books can be updated and corrected constantly; readers can be linked to related subjects via live footnotes. You can even scribble your notes electronically on the margins and then share them.

Professor Darnton recognizes the huge possibilities of the digital media. He recently published a history book which includes songs that can be accessed via the internet and listened to while you’re reading the book. ‘So we’re taking in history through the ear as well as through the eye.’ And what of the printed book, apart from its smell? At a practical level, we only need our eyes and hands to read it: no electricity, batteries or internet access necessary. We like to own books, to collect them, to display them on our shelves. Our favourite books have bits of ourselves in them. It may be that at the end of this transitional period when print and digital co-exist, the printed book will become the preserve of the few. Those who like to turn a physical page are already able to go to a shop, order a digitized text, and it’s printed, trimmed and bound within four minutes. As someone (probably a publisher) once said, as long as authors have a mother, they’ll want to give her a copy of their book.

Some very big questions are being asked about the future of written language — not in the next few centuries but in the next tens of thousands of years. Given the difficulties we have in reading the Old English of Beowulf , let alone in decoding the early writing systems of 5,000-year-old civilizations, how can we make our language readable to peoples of the future? The American government has been wrestling with the problem of how to warn future generations about the spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste which they have been burying in underground chambers deep in the Mojave Desert. The waste will remain dangerous for at least 10,000 years. No one knows which languages, if any, will be spoken by AD 12,000, give or take a year or so. So how will we warn the future about the risks?

In 1984 the late linguist Thomas Sebeok was asked to come up with suggestions for the most effective ‘keep out’ signs. Sebeok argued that, in 10,000 years, all the world’s spoken and written languages would likely have faded away. So he recommended the use of warning signs and symbols and the creation of what he called an ‘atomic priesthood’ of scientists and scholars who could pass down the knowledge about the danger of the site from generation to generation. These priests would also be tasked with passing on ‘artificially created and nurtured ritual-and-legend’ myths about evil spirits so that people would be too scared to go near the site.

In the 1990s, a team of linguists, scientists and anthropologists was commissioned to design the warning system for the Mohave Desert nuclear dump site. The art designer on the team is Jon Lomberg, one of the world’s leading space artists, who illustrated most of astronomer Carl Sagan’s books. Lomberg has created some of the most durable and far-flung objects ever produced by a human being. His design for the aluminium jacket cover of the Voyager spacecraft’s Interstellar Record message from the people of Earth is intended to last for a thousand million years. This is definitely a man who knows a thing or two about messages for the future. And trying to talk to aliens has given us some ideas about how best we might create meaningful messages for the generations 10,000 years ahead of us.

Lomberg explains how straightaway the Mohave Desert design team rejected the idea of a magic bullet — one perfect way of solving the problem. They decided on a shotgun approach, looking for a variety of options. Their first thought was to go for picture symbols.

‘People change, culture changes; what we looked for was what was invariant. In the case of languages we know that languages evolve and have a half life. For most of us Shakespeare can be a little tricky to read, Chaucer difficult and Beowulf impossible. And that’s just one thousand years. Pictures, on the other hand, do seem to be universal. We can recognize the animals on the walls of the caves, and one of the common motifs that you find in art all over the world is the stylized picture of a human. A stick figure … You can tell it’s a person and you can tell if it’s standing up or lying down and what they’re doing — running, throwing a spear, sitting on a throne … Symbols are a sort of a mid-point. A symbol in a sense is a word that doesn’t need translation.’

But Lomberg and his team discovered that there are actually very few universal symbols. Carl Sagan wrote to the team to suggest that the skull and crossbones be used as the symbol of danger and death. Yet it changes in meaning from culture to culture. In the Middle Ages it represented the resurrection of Christ and symbolized hope. It was only when it was put on gravestones that it began to be associated with death and later with the Jolly Roger pirate’s flag.

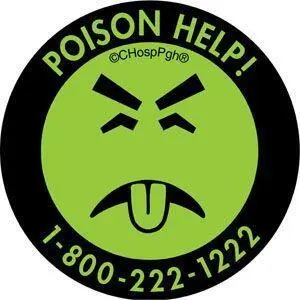

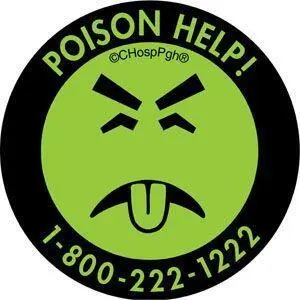

Mr Yuk. Will language as we know it no longer exist in the future?

The team decided to use double symbols — the skull and crossbones plus the Mr Yuk figure, a frowny face with a tongue sticking out which is widely used in the United States as the symbol for poison.

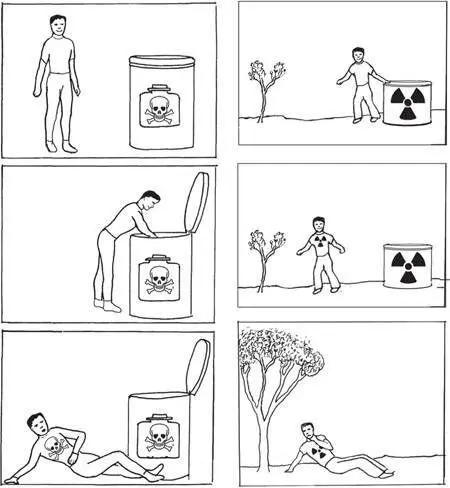

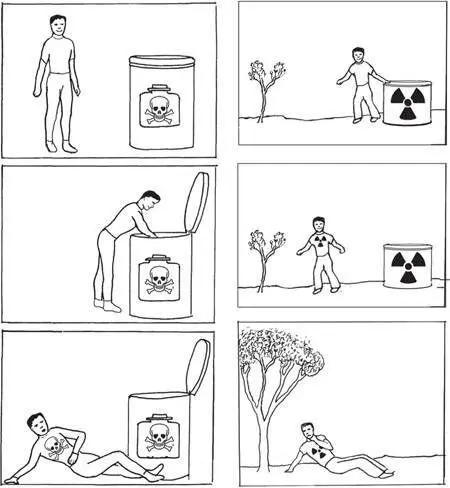

‘The other thing that seems to be universal is the notion of a storyboard,’ says Lomberg, ‘a series of drawings that show a series of events in time. We find it in the Bayeux Tapestry, in the scrolls of Japan that depict the invasion by the Mongols.’ Lomberg started his art career drawing comics and was keen to explore the idea that the symbols could be defined within a comic strip story. He believes that, although comic strips are without language, like a Charlie Chaplin movie their language is universal. Crude cartoons were drawn, each picture cell stacked from the top down since, although not all cultures read from right to left, they all read from top to bottom.

Comic Strip 1 Comic Strip 2

Comic strip 1 shows a person removing something from a container with the poison symbol on it; the poison symbol appears on their chest and they fall on the ground and die. Comic strip 2 is a warning about the long-term effect of the poison. A child is shown going into a container that’s marked with the radiation symbol. The same person is next seen as an adult — we know time has passed because the tree in the background has grown tall — and then he’s falling down. The symbols, comic strips and warnings in the six official languages of the UN will be etched into a series of markers — granite pillars erected around the nuclear waste site. Lomberg and his team have until 2028 to submit their final plan.

Lomberg and a number of the team members have a background in SETI, the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence. They helped choose the messages carried by the Voyager spacecraft into outer space in 1977, including recordings of greetings in fifty-five languages. Impossible to know what an alien will make of ‘Hello from the children of Planet Earth’, but, as Carl Sagan pointed out at the time, perhaps the most important impact of the message will be that we cared enough to try to communicate.

Читать дальше