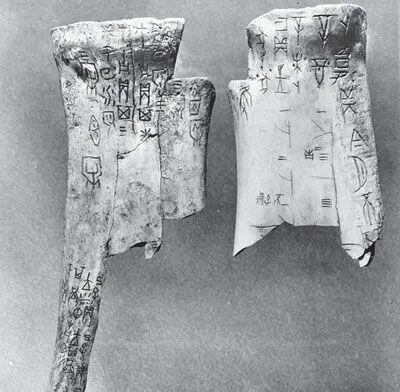

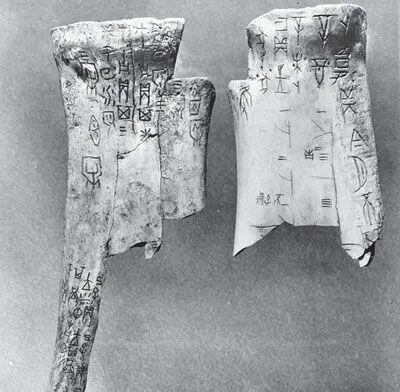

Chinese oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty

So the ideograms either modify existing pictographs or are direct symbolic illustrations. For instance, by modifying  dāo , a pictogram for ‘knife’, by marking the blade, you get an ideogram

dāo , a pictogram for ‘knife’, by marking the blade, you get an ideogram  rèn for ‘blade’. The ideogrammic compounds symbolically combine pictograms or ideograms to create a third character. For instance, doubling the pictogram

rèn for ‘blade’. The ideogrammic compounds symbolically combine pictograms or ideograms to create a third character. For instance, doubling the pictogram  mù , ‘tree’, produces

mù , ‘tree’, produces  lín , ‘grove’, while tripling it produces

lín , ‘grove’, while tripling it produces  sēn , ‘forest’. Similarly, combining

sēn , ‘forest’. Similarly, combining  rì , ‘sun’, and

rì , ‘sun’, and  yuè , ‘moon’, the two natural sources of light, makes

yuè , ‘moon’, the two natural sources of light, makes  míng , ‘bright’.

míng , ‘bright’.

Zhou Youdong, creator of Pinyin

Not surprisingly, literacy rates were very low when Mao came to power. Sir David lets on that the man who more than anyone changed the way Chinese now learn to read and write is still alive. His name is Zhou Youdong, and he was entrusted by Mao with the total overhaul of the Romanization of Chinese.

Zhou Youdong is 106 years old but looks a decade or three younger. He has survived more revolutions, counter-revolutions, great leaps forward and giant leaps backwards than Newcastle United FC. He lives with his eighty-five-year-old son in one of those drab communist-era housing projects that so disfigure the Chinese capital.

Zhou was living in the USA before Mao came to power, studying economics. But in 1950 he decided to return as he was keen to help in the modernization programme of the communists. At that time there was a rather complicated system of Romanization of the written language which was not very effective. The difficulty of learning the characters had held back literacy rates so that when Mao came to power only 20 per cent of the country was literate. It was very important to improve this if China was to become a modern state. In 1955 Mao asked Zhou to make a new system; it took him and his colleagues six years to complete. Two decades after the revolution literacy rates had improved to 80 per cent and now they are about 90 per cent. Without doubt Pinyin, as Zhou’s Romanization is called, has done more for developing China than almost anything else one can think of. Yet Zhou remains modest about his achievements. Was Mao Tse Tung grateful? Diplomatically Zhou answers, ‘Mao Tse Tung supported the work.’ Pinyin is now taught in every school in China, and its phonetic-based Romanization system allows children to write Mandarin (on which it is based) much faster than the old way of learning all the characters by heart. Moreover, it revolutionized the way you type, especially important in a country that texts more than the rest of the world combined. Without Pinyin this would simply not be possible.

There had been an earlier Anglicization of Chinese made by Thomas Wade in 1859 and modified by Herbert Giles in 1892, but it was more for foreigners than for Chinese. This system uses English consonants and vowels to approximate the phonology of Mandarin Chinese. This is the system that gives us Peking and Mao Tse-Tung rather than Beijing and Mao Zedong . In truth, neither of these systems really reproduce the sound of the Chinese, so we might as well stick with saying Peking rather than mangle the Mandarin of Beijing , which will sound all wrong, as we can never get the tone right.

We’ve seen how the invention of writing changed the human world utterly. With writing, we could preserve, record and shape our stories, communicate our ideas and extend the significance of our lives beyond their end. Writing gave us our history.

Over the 5,000 years since writing was invented, hundreds of different languages have been written in hundreds of different scripts. For the vast majority of this time, everything was written by hand. But nearly 600 years ago there was a revolution in writing technology which changed, not just the face of writing, but the whole world. In the mid fifteenth century a man called Johannes Gutenberg invented a mechanical way of making books. His development of movable type printing started the printing revolution and is widely regarded as the most important event of the modern period.

Gutenberg’s achievement wasn’t that he was the single genius who invented printing in one inspired moment. Forms of printing had been used in different parts of the world long before Gutenberg came along. The Chinese had been working with type carved into wood and bronze for centuries. They had also invented paper made from a pulp of water and discarded rags which was then pressed into sheets for writing or printing on.

In the British Museum there’s a copy of the Diamond Sutra , one of the most sacred Buddhist texts and the world’s earliest complete survival of a dated printed book. The original was made in 868 and hidden for centuries in a sealed-up cave in north-west China. It’s made from seven strips of yellow-stained paper which were printed from carved wooden blocks and pasted together to form a scroll over 5 metres long.

Diamond Sutra , the oldest surviving printed book

Later on, the Chinese developed a movable type system using porcelain characters, and in the thirteenth century the Koreans were already experimenting with metal movable type made out of copper. The screw press, which Gutenberg refined and developed, had also been around for centuries to press grapes and impress patterns on textile.

What Gutenberg did was to combine different crucial elements and adapt them. He invented a process for mass-producing movable type — the individual pieces of type in metal, one for each character of the alphabet, punctuation and other signs, which could be set up to be printed on a printing press, and then reused over and over again. He used new oil-based instead of water-based ink. And he had the radical idea of using the traditional agricultural screw press for printing; up to then, impressions had been made from stamps or wood blocks, by pressing them on to paper or cloth or by putting paper on top of them and then rubbing to get an impression.

He brought these techniques together into a practical system which, as it developed, became increasingly efficient, economically viable and fast. In doing so he laid the foundation for mass production of books in Europe.

His printing press, which was in operation by 1450, played a key role in the development of the Renaissance, Reformation and the scientific revolution because it made possible the spread of learning and the sharing of knowledge on a huge scale. The written word escaped from the quill pens of the monks in their scriptorium and took flight out into the wide world.

Читать дальше

dāo , a pictogram for ‘knife’, by marking the blade, you get an ideogram

dāo , a pictogram for ‘knife’, by marking the blade, you get an ideogram  rèn for ‘blade’. The ideogrammic compounds symbolically combine pictograms or ideograms to create a third character. For instance, doubling the pictogram

rèn for ‘blade’. The ideogrammic compounds symbolically combine pictograms or ideograms to create a third character. For instance, doubling the pictogram  mù , ‘tree’, produces

mù , ‘tree’, produces  lín , ‘grove’, while tripling it produces

lín , ‘grove’, while tripling it produces  sēn , ‘forest’. Similarly, combining

sēn , ‘forest’. Similarly, combining  rì , ‘sun’, and

rì , ‘sun’, and  yuè , ‘moon’, the two natural sources of light, makes

yuè , ‘moon’, the two natural sources of light, makes  míng , ‘bright’.

míng , ‘bright’.